Advancements in drone technology have allowed for troops to use ever-smaller drones for their operations. But as with many other topics, online conspiracy theories have shoved aside legitimate discussions of these advances for the sake of pushing outlandish takes on them.

It is true, for example, that the United States Air Force pursued “Project Anubis,” designed to produce small armed drones. In 2010, the tech news magazine Wired reported that the project had been completed:

The military won’t say exactly what happened to this Project Anubis, named after a jackal-headed god of the dead in Egyptian mythology. But military budget documents note that Air Force engineers were successful in “develop[ing] a Micro-Air Vehicle (MAV) with innovative seeker/tracking sensor algorithms that can engage maneuvering high-value targets.”

Online speculation since, however, has fixated around “insect-sized drones,” to the point of circulating photos depicting robot bugs with microphones while sneeringly asking readers, “What have your taxes accomplished for YOU???”:

In reality, military applications like the “Black Hornet” drones featured in this January 2023 video more closely resemble small aircraft when seen up close:

The “Black Hornet” measures 16cm x 2.5 cm and weigh 18 grams when carrying a battery. It is small enough to fit inside a military operative’s pocket.

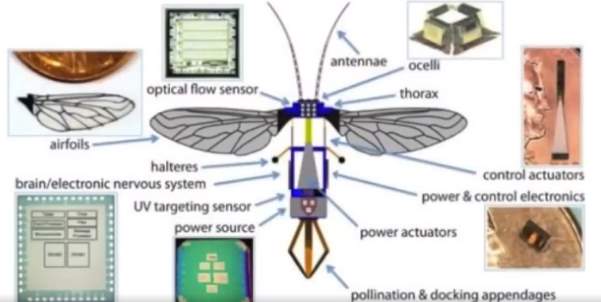

There has been similar speculation around “fly nano drones” purportedly being used by French troops, complete with faux schematics showing antennae and “pollination and docking appendages”:

In reality FLIR Systems, the Oregon-based company behind the “Black Hornets,” was paid $89 million in 2019 to provide the same drone to French forces.

We found that some photographs purportedly showing “insect spy drones” are taken from a real project, but one without military implications — Harvard University’s “Robobee Project,” which the university has said was designed to replicate the behavior of the drones’ namesakes:

Honeybee colonies regularly find and exploit resources within 2-6 km of their hive, adapt the number of bees exploring and exploiting multiple resources (pollen, nectar, water) based on the environment and needs of the colony, and can even recover when dramatic changes are made to their world.

In August 2018 the university announced that one of its “Robobees” became the lightest vehicle able to fly untethered, thanks in part to its own evolution — going from two wings to four.

“The change from two to four wings, along with less-visible changes to the actuator and transmission ratio, made the vehicle more efficient, gave it more lift, and allowed us to put everything we need on board without using more power,” said Noah T. Jafferis, who had worked for six years on the project up to that point.

Update 9/13/2023, 2:24 p.m. PST: This article has been revamped and updated. You can review the original here. — ag

- Air Force Completes Killer Micro-Drone Project

- What Can This $195,000 Black Hornet Drone Do?

- FLIR Systems Awarded $89 Million Contract from French Armed Forces to Deliver Black Hornet Personal Reconnaissance System

- Harvard University Self-Organizing Systems Research Group -- The Robobee Project

- The RoboBee Flies Solo