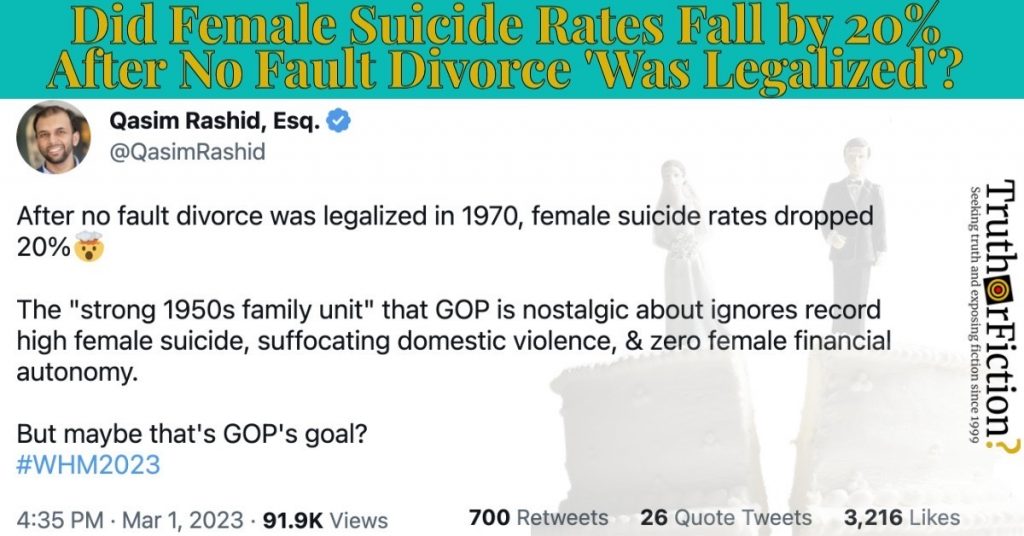

On March 8 2023 — International Women’s Day — an Imgur account circulated with a screenshot of a tweet by attorney Qasim Rashid, claiming that “female suicide rates” fell 20 percent in the years after no-fault divorce was introduced:

Neither post included a citation for the “20 percent” figure in the tweet. More broadly, a few elements of the tweet benefited from context about the underlying factors mentioned.

Fact Check

Claim: “After no fault divorce was legalized … female suicide rates dropped 20%.”

Description: The claim suggests that once no-fault divorce was legalized in 1970, female suicide rates experienced a significant decrease, specifically by around 20 percent.

What is No Fault Divorce, and Why Does It Differ from ‘Divorce’?

Commercial legal site LegalZoom’s entry on “no-fault divorce” indicates that it allows divorcing couples “to end your marriage without focusing on blame,” adding:

Originally, a married couple had to provide an acceptable reason for why they should be allowed to end their marriage and get a divorce. The reason for divorce is known as the grounds for divorce. California was the first state to offer no-fault grounds for divorce. Times have changed, and no-fault divorce is now available in all U.S. states.

What is no-fault divorce then? No-fault divorce allows one spouse to file for divorce without blaming the other or indicating that it was either spouse’s fault. The terminology differs with each state’s no-fault divorce laws, but to obtain a no-fault divorce, the spouse who files simply needs to state that there has been an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage, irreconcilable differences, or incompatibility. In some states, living apart for a specified period of time can be the reason for a no-fault divorce.

Cornell Law’s Legal Information Institute (LII)’s page about no-fault divorce explained a bit about the evolution of divorce. As was the case with LegalZoom’s entry, Cornell’s LII noted that divorce law remained state-specific in the United States:

No-fault divorce is the most common modern type of marriage dissolution. Traditional fault divorce required a person filing for divorce to prove some wrongdoing by their spouse that breached the marriage contract – cruelty, adultery, and desertion are common examples of grounds for a fault divorce. In contrast, no-fault divorces do not require any showing of wrongdoing. Rather, the filing spouse simply claims as grounds for the divorce that the couple cannot get along and the marriage has factually broken down. Depending on the state, the terminology used may be incompatibility, irreconcilable differences between the spouses, or irreparable breakdown of the marriage. All states now recognize no-fault divorce, and many have adopted pure no-fault divorce in which fault divorces are no longer recognized.

In states that offer both types of divorce, there can be strategic benefits to pursuing one type of divorce over another. In a no-fault divorce, the process is initiated unilaterally by the filing spouse and the other spouse cannot object. But depending on the state, no-fault divorces may require that the couple has lived separately for at least a minimum time period before filing. In contrast, fault divorces can be filed immediately upon a partner’s wrongdoing, however the filing spouse must have evidence available to prove their assertions of fault. The spouse who allegedly committed the wrongdoing can challenge the grounds for divorce and assert defenses that can stop the divorce. No-fault divorce is therefore more private because the couple does not have to share the intimate details of their marriage in court. But because fault divorces require a breach of the marriage contract, they often result in greater shares of the marital property or more alimony for the filing spouse than results from filing a no-fault divorce.

In the entry’s final paragraph, LII identified “the 1970s onward” as the advent of no-fault divorce in the United States:

No-fault divorce grew quickly in popularity among the states from the 1970s onward. The no-fault movement gained steam as an alternative to the tactics of perjury and forum-shopping employed by some unhappy couples to bypass their state’s fault divorce laws. However, critics of the pure no-fault movement – in which fault divorce is not an available option – have blamed no-fault divorce for many social ills, including rising divorce rates, increased bad marital behavior and domestic violence, and the destruction of the concept of mutual interdependence that was traditionally central to marriage.

Was No Fault Divorce Legalized in 1971?

Both excerpts above alluded to no-fault divorce spreading from state to state, with specific rules in each around the process of divorce.

Law firms often maintain legal explainer pages, and one such firm in New York State indicated that no fault divorce was not “legalized” in New York State until 2010:

Since 2010, New York has been a “no-fault” divorce state–the last state in the country to embrace this type of divorce. A no-fault divorce is one where a court may dissolve the marital union without requiring one spouse to prove that the other did something wrong. Instead, a spouse must simply show that the couple has “irreconcilable differences.”

Wikipedia’s entry on no-fault divorce stated that California was the first state to adopt it in 1969 (effective 1970), with New York last in 2010:

[As of March 2023], every state plus the District of Columbia permits no-fault divorce, though requirements for obtaining a no-fault divorce vary. California was the first U.S. state to enact a no-fault divorce law. Its law was signed by Governor Ronald Reagan, a divorced and remarried former movie actor, and came into effect in 1970. New York was the last state to enact a no-fault divorce law; that law was passed in 2010.

An October 2002 article published in the peer-reviewed journal Family Relations [PDF] (“The Effective Dates of No-Fault Divorce Laws in the 50 States”) focused on precisely when no-fault divorce was adopted in each state (a complete table of different dates per state appeared on page 320). Its authors further explained why those factors influenced research into divorce and marital dynamics, and emphasized that there was no definitive state-level legalization date for no-fault divorce, much less a nationally-applicable figure:

Researchers conducting some of the early work on this topic (e.g., Sepler, 1981; Wright & Stetson, 1978) acknowledged the difficulty in determining meaningful, consistent no-fault dates. At least one scholar (Sepler) suggested that future research needed to standardize divorce law date listings in major reference materials. As of this writing, no one has proposed a method or rule to determine no-fault divorce law dates across all states.

Finding the effective dates of the adoption of no-fault divorce laws can be both time-consuming and confusing. Conflicting no-fault dates appear in the social and political science literature, depending on what sources the researchers consulted when measuring the variable. The determination of the no-fault date also may be confused by the fact that many states amended or repealed no-fault laws once or more in the last three decades. The enactment date for a state’s no-fault law may be the only date listed in the literature and even in the annotated codes for each state. There may not be a notation of the date that the law actually went into effect and this often can be in the subsequent year.

The dates used by prominent researchers also diverge depending on the researcher’s definition of what constitutes a “no-fault” divorce law. Determination of an appropriate date would be easier if all states adopted similar statutes or used similar language to signal a change in divorce laws but this did not happen. In some states, the no-fault revolution was swift, dramatic, clear, and easily tracked in the state statutes. In many states, this revolution played out more slowly, with a gradual evolution toward full divorce law reforms. In such cases, it is fair to ask: At what point or date did the state statutes include wording that allowed the state to be classified as a no-fault state? Answering this question also raises the issue of whether, in the determination of the appropriate date, the researcher clearly articulated the decision rules and definitions governing his or her categorization of states, as these choices may reveal important philosophical or theoretical underpinnings of the research project.

In short, it was accurate to say no-fault divorce was gaining steam legally in 1971, but that it was not “legalized” in every state until 2010.

‘Female Suicide Rates’ and No-Fault Divorce

Initial searches turned up a post similar to the tweet shared to Reddit’s r/todayilearned on February 6 2012:

As is so often the case with years-old links shared to Reddit, the appended allbusiness.com link led to an error page in March 2023. A version of the link was archived in 2009, and the content itself was a 2004 partial press release titled “Stanford Business School Study Finds No-Fault Divorce Laws May Have Increased Women’s …”

A portion visible through the archived link suggested that research may have informed the claim in the tweet. It touched on the varying time frames by state, adding that researchers accounted for those differences when examining suicide rates in relation to changes in divorce law:

Divorce has traditionally left women financially worse off than men, but women may derive a life-preserving benefit from divorce, according to results of research by Professor Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson, a Harvard-trained economist. Examining the impact of no-fault divorce laws adopted by states in the 1970s and ’80s, they found decreased rates of suicide, domestic violence, and spousal homicide for women.

At the vanguard of an emerging field called household economics, Wolfers, an assistant professor of political economy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, used microeconometric techniques. He and Stevenson weighed the changes in the bargaining threat point: Like workers and employers, a husband and wife can produce more together than separately. In labor markets, workers demand a certain share of the joint product or they exercise their options to go elsewhere. In marriage, “a husband and wife can each threaten the other implicitly if each has outside options,” Wolfers said.

No-fault divorce laws allow one person to dissolve a marriage without the consent of the spouse. In most states before no-fault, divorce required consent of both or proof of fault by the non-consenting spouse. “Under no-fault wives can always threaten to walk out without the husband’s permission, changing the power balance in the relationship,” Wolfers said. The husband, understanding the lowered threat point, behaves himself, thereby reducing the incidence of domestic violence and spousal homicide — and increasing women’s wellbeing, he argues.

Because states changed their divorce laws at different times, the researchers could examine the impact in state-by-state comparisons. For example: California changed its law in 1969, Massachusetts in 1975. “If we expect the suicide rate to fall, we expect it to fall six years earlier in California than in Massachusetts,” said Wolfers.

Tapping into the national database of death certificates, Wolfers and Stevenson traced suicide rates before and after divorce reform and found a statistically significant reduction of nearly 6 percent in the female suicide rate following a state’s change to unilateral divorce. There was no discernible change in male suicides. Looking longer term, they found close to a 20 percent decline in female suicides 20 years after the change to no-fault divorce.

If the link originally went to the research it described, it was no longer present on the archived page. A search for the names of the researchers, “female suicide rates,” and “no-fault divorce” led to a December 2003 “working paper” published by the non-partisan National Bureau of Economic Research, or NBER [PDF, “Bargaining In The Shadow Of The Law: Divorce Laws And Family Distress.”]

An abstract for the paper read:

Over the past thirty years [before December 2002, or 50 years as of 2022] changes in divorce law have significantly increased access to divorce. The different timing of divorce law reform across states provides a useful quasi-experiment with which to examine the effects of this change. We analyze state panel data to estimate changes in suicide, domestic violence, and spousal murder rates arising from the change in divorce law. Suicide rates are used as a quantifiable measure of wellbeing, albeit one that focuses on the extreme lower tail of the distribution. We find a large, statistically significant, and econometrically robust decline in the number of women [dying by] suicide following the introduction of unilateral divorce. No significant effect is found for men. Domestic violence is analyzed using data on both family conflict resolution and intimate homicide rates. The results indicate a large decline in domestic violence for both men and women in states that adopted unilateral divorce. We find suggestive evidence that unilateral divorce led to a decline in [women] murdered by their partners, while the data revealed no discernible effects for men murdered. In sum, we find strong evidence that legal institutions have profound real effects on outcomes within families.

In the paper’s “Introduction” section, the figure of 20 percent appeared (a similar PDF paper from NBER in 2006 defined “unilateral divorce” as part of a “‘no-fault revolution’ that swept the United States in the 1970s”):

We find that states that passed unilateral divorce laws saw a large decline in both female suicide and domestic violence rates. Total female suicide declined by around 20% in states that adopted unilateral divorce. There is no discernable effect on male suicide. Our data on spousal conflict suggest that a large decline in domestic violence occurred in reform states. Furthermore, our results suggest a decline in women murdered by intimates, although the timing evidence is less supportive of this claim. As with suicide, there is no discernable effect on males murdered.

In March 2004, NBER published “Divorce Laws and Family Violence,” subtitled:

States that passed unilateral divorce laws saw total female suicide decline by around 20 percent in the long run.

It summarized the working paper, and read in part:

The authors [found] very real effects on the well being of families. For example, there was a large decline in the number of women [dying by] suicide following the introduction of unilateral divorce, but no similar decline for men. States that passed unilateral divorce laws saw total female suicide decline by around 20 percent in the long run. The authors also [found] a large decline in domestic violence for both men and women following adoption of unilateral divorce. Finally, the evidence suggests that unilateral divorce led to a decline in females murdered by their partners, while the data reveal no discernible effects for homicide against men.

The same authors (Stevenson and Wolfers) published “Til Death Do Us Part: Effects of Divorce Laws on Suicide, Domestic Violence and Spousal Murder” in 2000, with an abstract reading:

Over the past thirty years [as of 2000, 53 as of 2023] changes in divorce law have significantly increased access to divorce. The different timing of divorce law reform across states provides a useful quasi-experiment with which to examine the effects of this change. We analyze state panel data to estimate changes in suicide, domestic violence and spousal murder rates arising from the change in divorce law. Suicide rates are used as a quantifiable measure of happiness and well-being, albeit one that focuses on the extreme lower tail of the distribution. We find a large, statistically significant, and econometrically robust decline in the number of women [dying by] suicide following the introduction of unilateral divorce. No significant effect is found for men. Domestic violence is analyzed using both data on family conflict resolution, and intimate homicide rates. The results indicate a large decline in domestic violence for both men and women in states that adopted unilateral divorce. We find suggestive evidence that unilateral divorce led to a decline in females murdered by their partners, while the data revealed no discernible effects for men murdered. In sum, we find strong evidence that legal institutions have profound real effects on outcomes within families.

Rashid’s figure of a 20 percent drop in female suicide rates after the introduction of unilateral or no-fault divorce was substantiated, and appeared to originate with research published in connection with NBER in the early 2000s.

Summary

A popular March 8 2023 Imgur post showed a tweet by attorney Qasim Rashid which claimed that after no-fault divorce was legalized in 1970, female suicide rates dropped 20 percent. No-fault divorce was adopted on a state-by-state basis in the United States, starting with California in 1969 and ending with New York in 2010. Roughly three decades after the first laws were introduced, researchers examined the long-term effects on female suicide rates, and they identified “a large, statistically significant, and econometrically robust decline in the number of women [dying by] suicide following the introduction of unilateral [no-fault] divorce.”

- 'After no fault divorce was legalized in 1970, female suicide rates dropped 20' | Imgur

- 'After no fault divorce was legalized in 1970, female suicide rates dropped 20' | Twitter

- What is no-fault divorce?

- no-fault divorce | Cornell Law School LII

- new york is a no-fault divorce state

- No-fault divorce | Wikipedia

- The Effective Dates of No-Fault Divorce Laws in the 50 States

- TIL the adoption of no-fault divorce laws led to a 20% female suicide drop and an even bigger domestic violence reduction after 20 years. | Reddit

- Stanford Business School Study Finds No-Fault Divorce Laws May Have Increased Women's...

- BARGAINING IN THE SHADOW OF THE LAW: DIVORCE LAWS AND FAMILY DISTRESS | NBER

- Did Unilateral Divorce Laws Raise Divorce Rates? A Reconciliation and New Results | NBER

- Divorce Laws and Family Violence | NBER

- Til Death Do Us Part: Effects of Divorce Laws on Suicide, Domestic Violence and Spousal Murder.”