Ride-sharing company Lyft came under increased scrutiny online in November 2019 as social media users spotted an apparent discrepancy in its policies regarding its treatment of sexual assault victims.

“I think what we saw happen in the last 24, 36 hours is you see what happens when someone like myself or other survivors share their stories and trauma becomes humanized,” said Alison Turkos, whose story as a survivor of rape was brought back into the public eye again as part of the criticism against Lyft.

The discussion began on November 4 2019, when Amelia Bonow, co-founder of the advocacy group Shout Your Abortion, shared Turkos’ September 2019 first-person account of the attack against her two years earlier.

Turkos wrote:

My Lyft driver kidnapped me at gunpoint, drove me across state lines, and, along with at least two other men, gang raped me.

Within 24 hours, I reported my kidnapping to Lyft. Lyft “apologized for the inconvenience that I’d been through” and informed me they “appreciated the voice of their customers and were committed to doing their best in giving me the support that I needed”. However, to my utter shock, Lyft informed me that I would still be expected to pay for the original estimated cost of my ride and I would be “unpaired” from the driver in the future — I’d later learn he remained a Lyft driver.

Turkos subsequently sued Lyft, arguing that Lyft actually continued to let the driver who raped her drive for the company. As of October 2019, at least 34 women have reportedly either sued or joined lawsuits against Lyft related to sexual assault at the hands of its drivers.

Her story gained more traction online when journalist Christine Grimaldi highlighted a clause in Lyft’s terms of service limiting survivors’ options after an attack.

“Under Lyft’s new terms of service, customers must waive their right to a bench or jury trial,” she wrote:

They’re forced into individual arbitration with the company instead, and class arbitrations are banned. Is this how Lyft plans to evade sexual assault lawsuits? What the fuck?

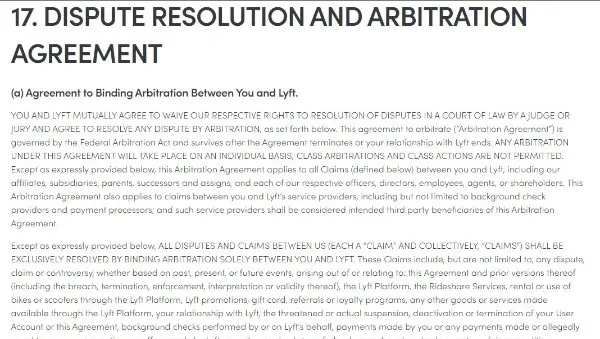

Lyft’s terms of service, last updated in August 2019, state:

YOU AND LYFT MUTUALLY AGREE TO WAIVE OUR RESPECTIVE RIGHTS TO RESOLUTION OF DISPUTES IN A COURT OF LAW BY A JUDGE OR JURY AND AGREE TO RESOLVE ANY DISPUTE BY ARBITRATION, as set forth below. This agreement to arbitrate (“Arbitration Agreement”) is governed by the Federal Arbitration Act and survives after the Agreement terminates or your relationship with Lyft ends. ANY ARBITRATION UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL TAKE PLACE ON AN INDIVIDUAL BASIS; CLASS ARBITRATIONS AND CLASS ACTIONS ARE NOT PERMITTED.

The company, along with its competitor Uber, had announced in 2018 that they would stop requiring arbitration in cases involving sexual assault or harassment. A Lyft spokesperson, Dana Davis, told us that the company has not changed its terms of service. But the document’s section on exceptions to the arbitration requirement does not mention harassment or assault. Instead it reads:

This Arbitration Agreement shall not require arbitration of the following types of claims: (1) small claims actions brought on an individual basis that are within the scope of such small claims court’s jurisdiction; (2) a representative action brought on behalf of others under PAGA [the Private Attorneys General Act of 2004] or other private attorneys general acts, to the extent the representative PAGA Waiver in Section 17(c) of such action is deemed unenforceable by a court of competent jurisdiction under applicable law not preempted by the FAA; (3) claims for workers’ compensation, state disability insurance and unemployment insurance benefits; and (4) claims that may not be subject to arbitration as a matter of generally applicable law not preempted by the FAA.

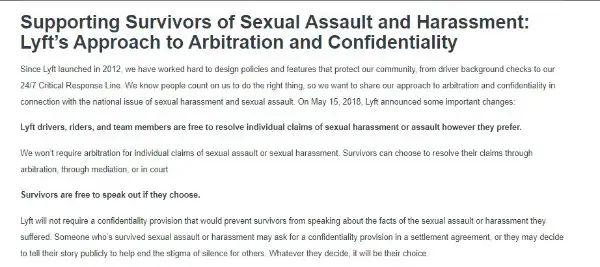

The terms of service also apparently contradict a statement in the company’s page covering safety policies:

Lyft drivers, riders, and team members are free to resolve individual claims of sexual harassment or assault however they prefer.

We won’t require arbitration for individual claims of sexual assault or sexual harassment. Survivors can choose to resolve their claims through arbitration, through mediation, or in court.

Survivors are free to speak out if they choose.

Lyft will not require a confidentiality provision that would prevent survivors from speaking about the facts of the sexual assault or harassment they suffered. Someone who’s survived sexual assault or harassment may ask for a confidentiality provision in a settlement agreement, or they may decide to tell their story publicly to help end the stigma of silence for others. Whatever they decide, it will be their choice.

Turkos told us she was confused by that discrepancy.

“It, to me, reads as if there’s nothing binding or contractual,” she said. “It’s only a public statement which obviously is nothing but false promises and smoke and mirrors.”

The story spread further when a tweet from writer Lauren Rankin supporting Turkos was turned into a graphic for a feminist Facebook group and shared more than 3,000 times.

Turkos said that she did not plan for the increased attention to her story. But as more social media users began using the hashtag “#CancelLyft” to discuss the issue, she said she would continue to push for systemic change within the ride-share industry.

“I will use any form possible and I will ask everyone to join with me,” she said. “It’s not just one person. I am not the only person who has been harmed.”