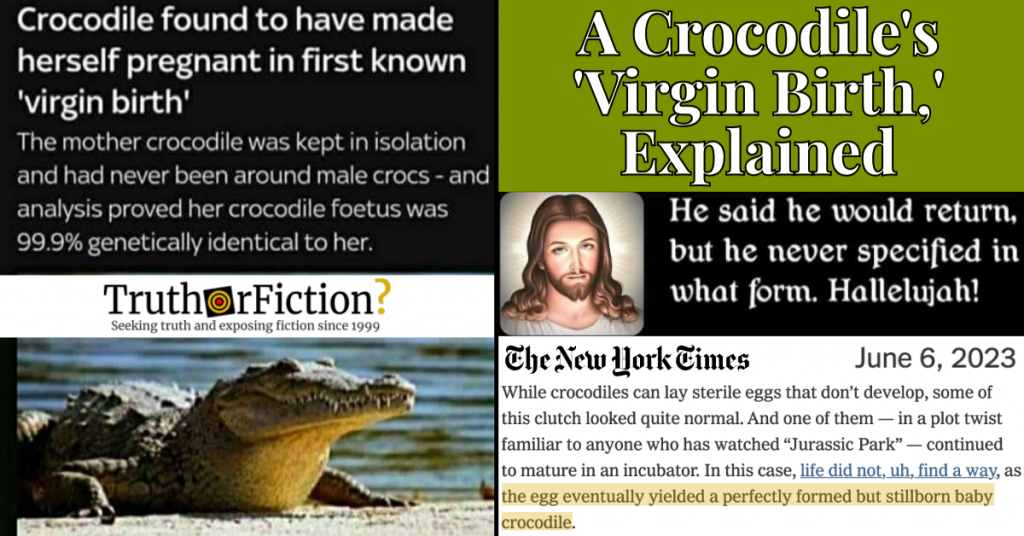

On June 27 2023, the concept of parthenogenesis made its way around social media after an Imgur user shared a meme about a crocodile’s “virgin birth” in the form of a screenshot:

No date for the headline was visible in the screenshot, nor did it include any identifying information about its source. Text of the screenshot (including a comment about Jesus) read:

Fact Check

Claim: In 2023, scientists published evidence of a “virgin birth” involving a crocodile.

Description: In 2023, scientists published evidence of a ‘virgin birth’ involving a crocodile. The crocodile in question, named Coquita, had been living alone in a Costa Rican zoo called Parque Reptilandia for 16 years before laying a very special clutch of eggs in 2018. One of those eggs was later found to contain a fully formed crocodile fetus, despite the fact that Coquita had lived virtually her entire life in isolation. There was almost no chance she had consorted with male crocodiles.

Crocodile found to have made herself pregnant in first known ‘virgin birth’

The mother crocodile was kept in isolation and had never been around male crocs – and analysis proved her crocodile foetus was 99.9% genetically identical to her.

[Image of Jesus] He said he would return, but he never specified in what form. Hallelujah!

A search for the headline led to a partial match on June 7 2023 on BBC.com. But the entire headline and subheading matched with a June 7 2023 Sky News article, which reported in part:

The foetus was 99.9% genetically identical to the mother, confirming it had no father.

Virgin births, or parthenogenesis, have been documented in birds, lizards, snakes and fish, but never before in crocodiles.

The crocodile in question was 18 when she laid a clutch of eggs in 2018.

On June 9 2023, CNN’s “A crocodile in Costa Rica had a virgin birth. Here’s what that means” explained that the news originated with newly published research on a newly documented instance of parthenogenesis in that species:

The crocodile in question, named Coquita, had been living alone in a Costa Rican zoo called Parque Reptilandia for 16 years before laying a very special clutch of eggs in 2018. One of those eggs was later found to contain a fully formed crocodile fetus, despite the fact that Coquita had lived virtually her entire life in isolation. There was almost no chance she had consorted with male crocodiles.

It was clear evidence — presented for the first time in a paper published in the journal Biology Letters on June 7 [2023] — that crocodiles are capable of a type of reproduction called parthenogenesis, in which unfertilized eggs can yield offspring.

Parthenogenesis is defined as:

… a reproductive strategy that involves development of a female (rarely a male) gamete (sex cell) without fertilization. It occurs commonly among lower plants and invertebrate animals (particularly rotifers, aphids, ants, wasps, and bees) and rarely among higher vertebrates. An egg produced parthenogenetically may be either haploid (i.e., with one set of dissimilar chromosomes) or diploid (i.e., with a paired set of chromosomes). Parthenogenic species may be obligate (that is, incapable of sexual reproduction) or facultative (that is, capable of switching between parthenogenesis and sexual reproduction depending upon environmental conditions). The term parthenogenesis is taken from the Greek words parthenos, meaning “virgin,” and genesis, meaning “origin.” More than 2,000 species are thought to reproduce parthenogenically.

CNN linked to the journal Biology Letters, which published a June 7 2023 paper (“Discovery of facultative parthenogenesis in a new world crocodile”). Its abstract indicated that researchers had identified the only evidence of parthenogenesis in crocodiles, to the best of their knowledge:

Over the past two decades [as of June 2023], there has been an astounding growth in the documentation of vertebrate facultative parthenogenesis (FP). This unusual reproductive mode has been documented in birds, non-avian reptiles—specifically lizards and snakes—and elasmobranch fishes. Part of this growth among vertebrate taxa is attributable to awareness of the phenomenon itself and advances in molecular genetics/genomics and bioinformatics, and as such our understanding has developed considerably.

Nonetheless, questions remain as to its occurrence outside of these vertebrate lineages, most notably in Chelonia (turtles) and Crocodylia (crocodiles, alligators and gharials). The latter group is particularly interesting because unlike all previously documented cases of FP in vertebrates, crocodilians lack sex chromosomes and sex determination is controlled by temperature.

Here, using whole-genome sequencing data, we provide, to our knowledge, the first evidence of FP in a crocodilian, the American crocodile, Crocodylus acutus. The data support terminal fusion automixis as the reproductive mechanism; a finding which suggests a common evolutionary origin of FP across reptiles, crocodilians and birds.

With FP now documented in the two main branches of extant archosaurs, this discovery offers tantalizing insights into the possible reproductive capabilities of the extinct archosaurian relatives of crocodilians and birds, notably members of Pterosauria and Dinosauria.

In the abstract, “to the best of our knowledge” alluded to some uncertainty, echoed in additional reporting. On June 6 2023, the New York Times provided context for the findings in layman’s terms, reporting:

In this case, life did not, uh, find a way, as the egg eventually yielded a perfectly formed but stillborn baby crocodile … Here’s how a virgin birth happens: As an egg cell matures in its mother’s body, it divides repeatedly to generate a final product with exactly half the genes needed for an individual. Three smaller cellular sacs containing chromosomes, known as polar bodies, are formed as byproducts. Polar bodies usually wither away. But in vertebrates that can perform parthenogenesis, one polar body sometimes fuses with the egg, creating a cell with the necessary complement of chromosomes to form an individual.

That’s what appears to have happened in the case of the crocodile, said Warren Booth, an associate professor at Virginia Tech who has studied the eggs. Dr. Booth is an entomologist whose main focus is bedbugs, but he has an extensive sideline in identifying parthenogenesis. Sequencing of the parthenogenetic crocodile’s genome suggests that its chromosomes differ from the mother’s at their tips, where there’s been a little reshuffling of her DNA — a telltale sign of polar body fusion.

A June 27 2023 Imgur post referenced a crocodile’s “virgin birth.” On June 7 2023, researchers published a paper in Biology Letters, disclosing evidence of a “virgin birth” (parthenogenesis) in a crocodile in Costa Rica. Context absent from the headlines included the authors’ caveat (“to the best of our knowledge,”) as well as details about the fate of the baby crocodile (which was stillborn). As such, we rated the claim Decontextualized.

- Crocodile virgin birth | Imgur

- Crocodile found to have made herself pregnant

- Crocodile found to have made herself pregnant in first known 'virgin birth'

- A crocodile in Costa Rica had a virgin birth. Here’s what that means

- Parthenogenesis | Brittanica

- Discovery of facultative parthenogenesis in a new world crocodile

- Scientists Discover a Virgin Birth in a Crocodile