After a January 3 2020 United States-led strike killed Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Suleimani in Baghdad, Iraq, speculation flew about impending war, eventually turning into rumors about an American military draft.

On the day Suleimani was killed, news organizations addressed the possibility of war with Iran:

A deadly opening attack. Nearly untraceable, ruthless proxies spreading chaos on multiple continents. Costly miscalculations. And thousands — perhaps hundreds of thousands — killed in a conflict that would dwarf the war in Iraq.

Welcome to the US-Iran war, which has the potential to be one of the worst conflicts in history.

Readers expressed anxiety and fear as they contemplated a new war, and several discussions turned to military recruiting and the possibility of a draft. Some people posted questions on Facebook about what a draft might look like in 2020:

I saw a meme somewhere claiming that being on antidepressants disqualifies you from the US military draft but haven’t found a definitive answer for whether that’s true. I see posts saying that if you want to join the military and have depression, then you could be disqualified, but if you still want to and can be considered stable, then you have a fair shot. What about people who would be forced to join thru a draft tho?

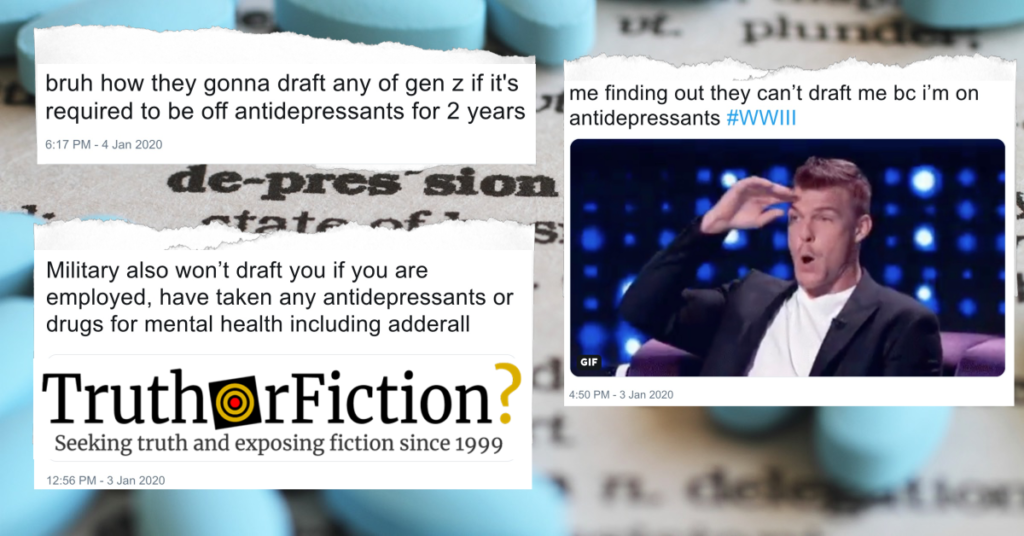

Concerns about the prospect of war with Iran and who might be conscripted for the potential conflict also emerged in meme form:

As usual, discourse also took place on Twitter, where speculation also involved ADHD medications like Adderall as possible draft disqualifiers:

All of these assertions were underpinned by uncertainty — both about whether a military draft could conceivably be in the cards, and whether something like having been prescribed Lexapro or Zoloft was sufficient to avoid being drafted or conscripted to fight a war.

For context, the last time the United States drafted anyone into service was 1973, nearly half a century prior to 2020 speculation about war with Iran. However, ongoing discussion about how a 2020 draft might appear was disrupted by a series of hoax text messages received by many Americans several days after Soleimani’s death.

On January 7 2020, the official United States Army Recruiting account tweeted out a fact check confirming that citizens had received text message notifications they’d been contacted about a draft:

Twitter users in the comments asked whether a draft could occur, and @usarec responded with information about the legislative structure of a draft:

U.S. Army Recruiting Command indicated in their fact check that they had received multiple queries about “fake text messages” announcing a draft, and clarified:

U.S. Army Recruiting Command has received multiple calls and emails about these fake text messages and wants to ensure Americans understand these texts are false and were not initiated by this command or the U.S. Army.

The decision to enact a draft is not made at or by U.S. Army Recruiting Command. The Selective Service System, a separate agency outside of the Department of Defense, is the organization that manages registration for the Selective Service.

“The Selective Service System is conducting business as usual,” according to the Selective Service System’s official Facebook page. “In the event that a national emergency necessitates a draft, Congress and the President would need to pass official legislation to authorize a draft.”

The draft has not been in effect since 1973. The military has been an all-volunteer force since that time. Registering for the Selective Service does not enlist a person into the military.

Army recruiting operations are proceeding as normal.

But as evidenced by the reply embedded above, worries about the draft nevertheless persisted. And an aspect of that lingering fear involved whether antidepressants (or therapeutic stimulants) disqualified people from being drafted.

As indicated in the U.S. Army Recruiting Command’s Twitter replies and fact check, no one has been drafted in the United States since 1973. As such, any information about a potential future draft can only be based on existing information regarding volunteer recruitment.

Privately-run resource Military.com hosted a FAQ about recruitment, and question number nine had to do with antidepressants and enlistment, not a draft. Answers were compiled from information submitted on forums “monitored and answered by real recruiters,” and the scope of the question about whether “anti-depressants disqualifying” was wide. Two answers were submitted, with a broad scope of application to putative draftees and recruits.

According to that information, antidepressants disqualified potential recruits for a year after ceasing to take the medication. Moreover, the answering recruiter said self-initiated cessation was insufficient to enlist. A second question appeared to have been answered by an Air Force member:

Response 1: Anti depressants are disqualifying for 1 year after you stop taking them. You MUST stop with your doctors advice, DO NOT stop on your own. These medications often have to be reduced slowly to lower side effects and reduce risk of relapse. Once you are off and depression free for 1 year get copies of your treatment paperwork, including therapy notes and take them with you to your recruiter. They will submit the documents to [United States Military Entrance Processing Command/Station, or MEPS] for review. MEPS will either DQ you, allow you to physical and enlist, or allow you to physical with a waiver (most likely).

Response 2: You’ll need to bring my medical records from the doctor who prescribed the anti-depressants. You’ll go to MEPS, take the [Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, or ASVAB] but your processing will be terminated at a certain point due to being honest about depression. Your records will be sent to the [Air Force] surgeon general’s office for review. This supposedly takes between six weeks and three months — mine took a full three months. If the waiver is granted, you’ll be cleared to return to MEPS. On your return trip, they’ll do a height/weight check then send you offsite to a psych consult. The doctor will then send his recommendation to MEPS where you will be reviewed further. This took nearly five weeks for me. If you are deemed fit for service, you will return to MEPS for job selection. Contrary to what I was initially told, depression rules out many jobs in the AF.

It appears that the military and its branches had a fluid and changing policy on mental health conditions, medication, and medical history. In November 2017, USA Today reported on a previously undisclosed policy allowing people with a medical history of mental illness to obtain waivers and serve:

People with a history of “self-mutilation,” bipolar disorder, depression and drug and alcohol abuse can now seek waivers to join the Army under an unannounced policy enacted in August [2017], according to documents obtained by USA TODAY.

The decision to open Army recruiting to those with mental health conditions comes as the service faces the challenging goal of recruiting 80,000 new soldiers through September 2018. To meet last year’s goal of 69,000, the Army accepted more recruits who fared poorly on aptitude tests, increased the number of waivers granted for marijuana use and offered hundreds of millions of dollars in bonuses.

U.S. Army spokesperson Lt. Col. Randy Taylor told the outlet that the new guidelines were not necessarily hard and fast ones:

“With the additional data available, Army officials can now consider applicants as a whole person, allowing a series of Army leaders and medical professionals to review the case fully to assess the applicant’s physical limitations or medical conditions and their possible impact upon the applicant’s ability to complete training and finish an Army career … These waivers are not considered lightly.”

In April 2018, ArmyTimes.com reported that relaxation of prior policies around medical and mental health histories had caused controversy following the November 2017 USA Today piece. Again, the specifics of the policy did not seem to be fully clear at that time, and Army higher-ups described the changes as something of a case-by-case basis adopted for children of servicemen and women with more comprehensive childhood records:

The Army’s personnel chief responded to the memo in November [2017] by clarifying that it was mistakenly distributed, but adding that the service was beginning to have more of an open mind about recruits’ mental health history.

“It’s also important to note that the conditions themselves have been unfairly characterized,” Lt. Gen. Thomas Seamands, the Army G-1, said in a statement at the time. “For example, a child who received behavioral counseling at age 10 would be forever banned from military service were it not for the ability to make a waiver request.”

… And in fact, it has been a concern for many military families. A spate of military children have been kicked out of initial military training after their childhood medical records were added to their service member records, sometimes revealing that they had turned to therapy as young children.

It was also, as noted, a focus on volunteer enlistment — not a policy enacted with a draft in mind:

“The waivers are really indicating to me that our recruiters are doing exactly what we’ve asked them to do,” Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey said [in April 2018]. “If they see something in the record that is of concern or is a question of meeting a DoD standard, they ask for somebody to review it.”

In January 2019, the Psychological Health Center of Excellence (or PHCoE, formerly known as the Deployment Health Clinical Center) Clinician’s Corner blog included an entry titled “Navy Changes Policy on Psychotropic Medications and Aviation.” It discussed whether a service member who was diagnosed with a mental health condition could maintain their military flight status during treatment, explaining:

Can a service member who has been diagnosed with a mental health disorder and is being treated with psychotropic medication maintain their military flight status while in treatment? YES! The use of psychotropic medications was disqualifying for U. S. Naval Aviators (pilots, flight officers, air traffic controllers and aircrew members) before November 2018. After this date, the U.S. Navy Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide (ARWG)(link is external) was updated to allow Navy and Marine Corps personnel who are on a stable dose of FDA-approved psychotropic medications to maintain their flight status during treatment.

According to the PHCoE blog, the first Navy waivers were granted in 2017 — around the time the first report disclosing the existence of waivers appeared:

The first waiver for a class of psychotropic medication use in Army aircrews was granted in 2004 for a diagnosis of chronic pain. Currently, Army aviators on stable doses of selected medications for most mental health diagnoses are eligible to maintain flight status. Similarly, Air Force policy allows designated personnel to fly while on monotherapy with one of four approved medications for treatment of specified conditions after the prescribed waiting periods officially went into effect in 2013. The Air Force is currently conducting a 20-year study to follow airmen on antidepressants, where results from the first five years found that no antidepressant medication has been associated with any Air Force mishap since the protocol started in 2013.

The first waivers granted in the Navy began in 2017, for diagnoses of major depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. Upon review of selected individuals, the Consult Advisory Board voted to allow aviators, in specified flying billets (e.g. dual-piloted, non-tactical aircraft), to be eligible for waiver consideration with continued therapy with FDA-approved psychotropic medication(s). Consideration for a waiver may be requested after a suitable period of observation in a non-flying status has elapsed, provided that the dose of the medication(s) is stable and the clinical condition is determined to be in stable remission. The duration of this period of observation in a non-flying status is dictated by the psychiatric diagnosis and is outlined in the relevant section of the ARWG.

Operation Military Kids’ “20 Health Conditions That May Not Allow You to Join the Military” page was updated on January 3 2020, and it contained a section on depression. According to that site, a history of depression (and presumably having taken antidepressants) might make it “difficult” (but not impossible) to enlist:

Since the U.S. Armed Forces deal with arming individuals with powerful weapons it must tread on mental health very carefully. Though people with mental health concerns are very good people that are still capable of living high-quality lives, the U.S. Military is very strict on how it handles mood disorders … [That] means that if you or someone you know that is considering enlisting in the U.S. Military has been diagnosed with [depression] in the past, it may be difficult to join.

Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were labeled “possibly disqualifying,” while bipolar disorder was described as “disqualifying.” Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder was also described as a disqualifying condition, with the following caveat:

The military is currently reexamining its approach for ADHD and has noted recently that it might start assessing circumstances on a case by case basis.

After conflict between the United States and Iran was initiated due to Suleimani’s death, speculation about war led to rumors that using antidepressants disqualified Americans from any military draft. An unrelated hoax exploited simmering draft fears, leading military recruiters to reiterate that reinstatement of the draft was a legislatively complicated process. Given that nearly half a century had passed since the previous active draft, the only up-to-date information available had to do with voluntary enlistment. As of 2017, the United States military had relaxed their policies about mental health and antidepressants to some degree, but those policies appeared to be in ongoing flux. Further, it was incredibly difficult to extrapolate how such fluid guidelines might apply to an involuntary enlistment process or draft. Because of this, we have rated this claim Decontextualized due to the complexity of its elements.

- “A nasty, brutal fight”: what a US-Iran war would look like

- Memes about 'WWIII' and 'military draft' inflate uncertainty; here's the truth

- U.S. Army Alert: You Are Not Being Drafted

- URGENT NEWS: Army Recruiting discredits military draft texts

- Military Entrance Processing Questions Answered

- Army lifts ban on waivers for recruits with history of some mental health issues

- Navy Changes Policy on Psychotropic Medications and Aviation

- 20 Health Conditions That May Not Allow You To Join The Military