Every day, a new fake story emerges with the power to affect policy or further corrode relationships, from interpersonal to international. This is corrosive disinformation, as different from garden-variety scams and hoaxes as a molehill is from a mountain.

The difference is intent — not just to mislead, but to defraud and misinform — and scale. Simple hoaxes cause a limited amount of harm, if any, and scams do harm people but do not have the power to change policy. But when misinformation is weaponized it can now travel around the world at lightning speed, affecting politics at all levels, usually for the worst.

Completely eradicating disinformation and propaganda is impossible given human nature and its propensity for embellishing or massaging information, but it can be effectively drowned out of the public discourse by vetted, responsible, and well-sourced journalism, the key to inoculating the public against wild rumors and poor policy based on them.

Until journalism has more funding and support from the general public, however, newsrooms can take some relatively easy steps to stop some of the worst fake news from going around. They are also not particularly time-consuming, they’re easy, and they’re free.

Pay attention to headlines. This is a big one. In the social media age, and particularly in the post-disinformation age, people get overwhelmed, even though they still want to know what’s happening around them. It’s natural. You can’t force people to read beyond the headline no matter how inviting it may be, but you can stop it from being co-opted.

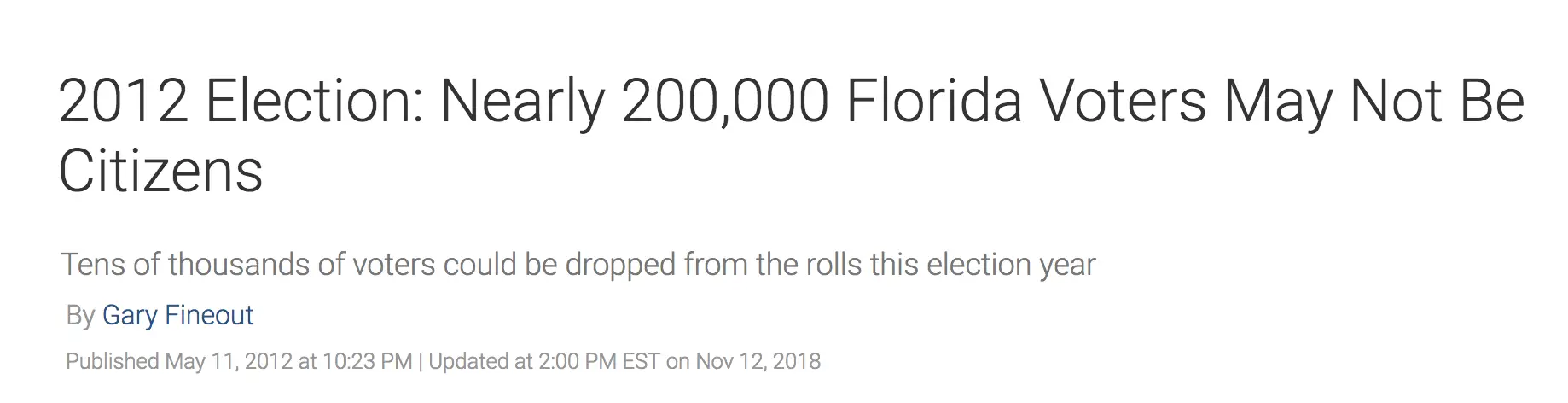

A perfect example of this took place during the 2018 midterms, when the NBC Miami station had an old article with a headline that was utterly shocking: “Nearly 200,000 Florida Voters May Not Be Citizens.”

In early November 2018, that story was shared again and again and appears to have been pushed for the sole purpose of making the 2018 midterm elections in Florida appear to be compromised in some way. It was not until you clicked on the story and read down that it became clear that it was from 2012, that it had been discredited in the months following and the program that the story was actually about had been discontinued after it became clear it was nothing more than a boondoggle.

This could have been avoided by simply changing the headline to reflect that the story was old, as the station eventually did:

You will lose some traffic to your site almost immediately, of course, since it’s no longer useful to disinformation purveyors, but if pandering to advertisers to make money is your first priority, then you are not doing journalism.

Pay attention to traffic. How can you know whether your stories are being used for disinformation purposes, particularly an old and forgotten one? That’s a little more tricky, but still an easy fix. Basic analytics apps will show what pages are getting hits and where they are coming from; if you inexplicably see an older story getting a lot of traffic with no clear reason, first look at the headline and then run a search for its verbiage on social media. (There are also apps and programs that you can use to do this for you, such as Algolia and CrowdTangle.) It is best to keep an eye on traffic as much as possible for this reason.

If you see a misleading article, all you need to do is change the title and add a disclaimer to the top of the page.

Check your sources. If you have a marginal “trend” story that you think is worth covering because people on the internet are talking about it, then follow it back to its source. Who is spreading this story and why? Who is talking about it, and why are they talking about it? What is the earliest possible iteration of this trend? That can help you distinguish between actual trends or controversies and astroturfed stories that do nothing but push a particular narrative (bots and paid trolls to get stories trending are among favorite tricks of disinformation purveyors on social media.)

Look for context. Sometimes newsrooms, pressed for time and understaffed as they are, unwittingly feed into disinformation by uncritically passing along what public figures or self-styled experts say without digging more into what they are actually saying. This goes back to the first rule of not spreading disinformation: Check your headlines.

Don’t do quote headlines. It doesn’t matter what people say if it’s a lie. Just assume that you’re writing for people who aren’t going to click, no matter what. Don’t use full quotes as headlines. That offers credence to what people are saying that they may not deserve, and even if what they’re saying is true it adds to an atmosphere in which people will believe any quote in a headline, even if it is completely false.

Value diversity. A diverse newsroom (cultural, ethnic, linguistic, gender-based, experience-based, et cetera) is more than simply a feel-good attempt at political correctness. It is a key strength in a world that houses multiple universes of experience. A variety of perspectives is key for fighting disinformation, which depends heavily on ignorance or fear of “the other.” An increasingly diverse world demands increasingly diverse newsrooms. Listen to other perspectives and honest criticism; trust but verify.

And finally…

Show your work. The old days of authoritative, “because I said so” journalism are over. Link to your sources. Show your notes. The internet has made a whole new world possible. “Open source” journalism is now not only possible, but should be the standard. Cries of “fake news” aren’t so loud when they are drowned out by plain, unvarnished truth. Certainly that is not always possible, particularly if you are dealing with sensitive topics or whistleblowers. In that case, explain why it is not possible.

The onus should not be on readers to painstakingly research the stories that they read and fit them into a geopolitical puzzle without proper training. Reporters should approach every story with a critical eye on not just detail, fact, and color, but also for nuance and — most importantly — its proper context.

To do otherwise runs the risk of working not as a journalist, but as nothing more than a stenographer for propaganda — against which journalism is supposed to be the first line of defense.