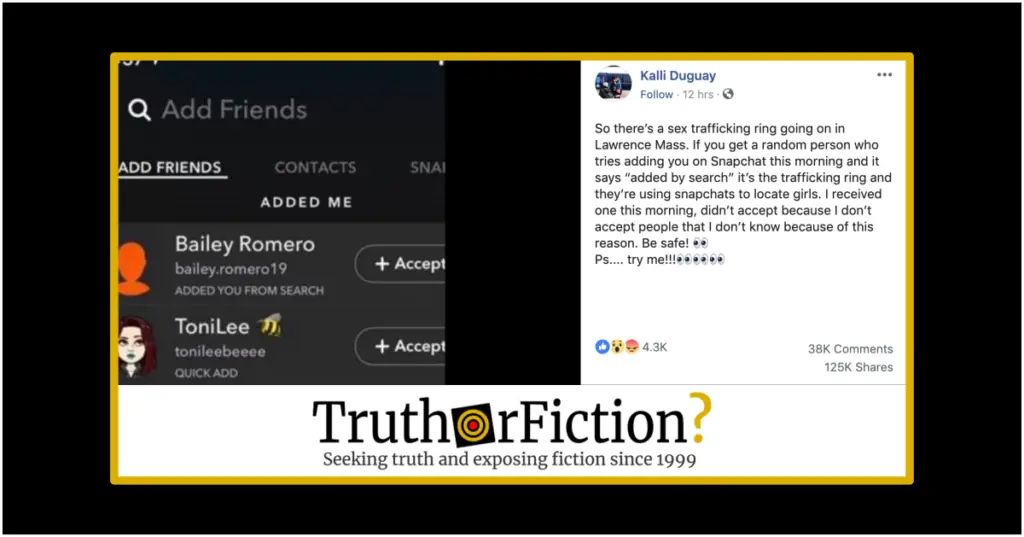

On April 24 2019, a Facebook user shared the following status (archived here), claiming that a Snapchat sex trafficking ring was operating in Lawrence, Massachusetts:

So there’s a sex trafficking ring going on in Lawrence Mass. If you get a random person who tries adding you on Snapchat this morning and it says “added by search” it’s the trafficking ring and they’re using snapchats to locate girls. I received one this morning, didn’t accept because I don’t accept people that I don’t know because of this reason. Be safe! ????

Ps…. try me!!!????????????

According to the poster, “a random person who tries adding you on Snapchat” was actually part of a ring of sex trafficking operatives. The post claimed that such a request originates with “the trafficking ring” and goes on to claim that “they’re using snapchats to locate girls.” She says that she avoided the risk by declining such a request, reminding fellow Snapchat users in Lawrence to “be safe.”

Missing from the post were important details, such as:

- An explanation of how Snapchat facilitated any “sex trafficking ring”;

- Evidence that Snapchat was used for “sex trafficking”;

- A link to any credible law enforcement information about Snapchat sex trafficking;

- A link to any news about Snapchat playing a role in then-recent sex trafficking in Lawrence or elsewhere

- An anecdote about any Snapchat “sex trafficking” whatsoever.

In its popular form (shared over 130,000 times in 12 hours), the claim was a classic sex trafficking scare with no basis in credible reality. We immediately contacted police in Lawrence, Massachusetts after checking their Facebook page for alerts — so far we have not seen any, and we left a message for the department.

Of course, a lack of any information substantiating the rumor or even the general claim about Snapchat as a sex trafficking risk was no barrier to opportunistic websites repeating the rumor as if it were news. According to the user, Snapchat sex traffickers were adding random women and using location services to find and abduct them.

However, research commissioned by the state of Nebraska in 2018 through the University of Toledo Human Trafficking and Social Justice Institute into the use of social media (including Snapchat) as a tool by sex traffickers revealed that location services were not the “real risk” faced by vulnerable populations. Dr. Celia Williamson, UT professor of social work and director of the UT Human Trafficking and Social Justice Institute, was one of several trafficking experts consulted by the state in its research.

Researchers found that while social media (and Snapchat) can be and has been used as a recruitment tool, the process did not involve “random women” and location services:

“The transition from messaging to meeting a trafficker in person is becoming less prevalent,” Williamson said. “As technology is playing a larger role in trafficking, this allows some traffickers to be able to exploit youth without meeting face-to-face. Social media helps to mask traditional cues that alert individuals to a potentially dangerous person.”

Williamson cites a 2018 report that says while 58 percent of victims eventually meet their traffickers face to face, 42 percent who initially met their trafficker online never met their trafficker in person and were still trafficked.

The experts, whose identities are not being released, said the traffickers educate themselves by studying what the victim posts on commonly used view-and-comment sites such as Facebook, Instagram or SnapChat, as well as dating apps such as Tinder, Blendr and Yellow, or webcam sites like Chatroulette and Monkey, in order to build trust.

“These guys, they learn about the girls and pretend to understand them, and so these girls, who are feeling not understood and not loved and not beautiful … these guys are very good at sort of pretending that they are all of these things and they really understand them and, ‘I know how you feel, you are beautiful,’ and just filling the hole that these girls are feeling,” said a professional contributing to the study.

Noting that predators tend to “look for indicators of substance abuse, runaway activity and destabilization within the home,” researchers concluded that one common tactic — again, not at all random — involved convincing someone who is already at risk to send a compromising photograph and then using that to extort them. Examples cited were far more involved than simple contact or adding of an unknown contact, and the victim typically communicated their location predators affirmatively (not passively):

One expert in Columbus shares a telling story: “The guy was reaching out to a lot of girls all day long. One girl, who is actually in a youth home, she had access to the Internet, and he connects with her on a social media platform. He drives all the way up from Columbus to Toledo, picks her up at her foster home and drives her back down to Columbus, and then traffics her here in Columbus. You know, 20, 30 years ago he would have never been able to connect with her, but because of social media, that connection was immediately made in over a few hours. He found out where she was and she told him, ‘Yeah, please come get me. I want out of here.'”

None of that information (nor any we could locate) suggested that Snapchat users in Lawrence, Massachusetts were at heightened risk of such tactics, nor even that Snapchat was riskier than the other platforms mentioned in the research (“Facebook, Instagram … Tinder, Blendr … Yellow … Chatroulette and Monkey”).

A September 2018 news story from Nebraska described grooming over social media in the case of one vulnerable 17-year-old who was later trafficked. In fact, a cadre of trafficking-related incidents in Nebraska curated by a religious organization detailed the actual tactics used by predators, none of which involved the simple act of determining a victim’s location through random requests. The cases did follow a pattern, which involved extensive contact between the predator and victim using a number of grooming tactics — often, the victim was shielded by police before they were intercepted by would-be traffickers.

The Lawrence, Massachusetts Snapchat sex trafficking rumor called to mind an earlier viral rumor about the purported use of Uber in sex trafficking claims in Florida. A viral Facebook post shared by a woman about a purportedly harrowing near-miss with traffickers using airport Ubers was later described by Tampa police as a “misunderstanding.” Tampa police were seemingly baffled about how a woman’s misidentification of Ubers spiraled into a breathless claim of trafficking at the airport:

It looks like the person who posted on Facebook got into the wrong car and then noticed that, you know, we are not going in the right direction. Well, they were going in the right direction — if it was the right person in the car. So it became very confusing. How that became some kind of sex trafficking thing is unclear to me and we’ve checked into it. The other driver is a legitimate Uber driver who was there to pick up somebody else.

As we noted in our page about that rumor, the claim was not as confusing to those familiar with the spread of fearmongering on social media. Lenore Skenazy of Free Range Kids described a similar viral frenzy involving a California IKEA in March 2017, expressing profound confusion over what she deemed a strange new form of bragging:

What the heck is going on, America? This “My kids were about to be trafficked, I just KNOW it” post is so shockingly similar to last week’s, “My kids were about to be trafficked, I just KNOW it” post that it feels … creepy. A lot creepier than being at Ikea where a couple of men glance at my kids.

The reader who sent me this link asked if I thought there might be some “validity” to it, to which I must respond: No. In fact, I think it’s crazy. What, two men are going to grab two or three kids, all under age 7, IN PUBLIC, in a camera-filled IKEA, with the MOM and the GRANDMA right there, not to mention a zillion other fans of Swedish furnishings?

Can we please PLEASE take a deep breath and realize how insanely unlikely that is? How we don’t need to be “warned” about this? How NOTHING HAPPENED!

You can TELL nothing happened, because the whole thing was described as an “incident.” And Lenore’s #1 Rule of Reporting is: When something is called an “incident,” it’s because nothing happened. In fact, my alternate headline for this post was:

POINTLESSLY TERRIFIED MOM URGES OTHER MOMS TO BE POINTLESSLY TERRIFIED

As we have noted, experts in trafficking routinely decry such claims about the issue. Experts regularly underscore the fact that sex trafficking is rarely (if ever) a “random” crime of sudden abduction; instead, traffickers tend to lure vulnerable teens over time:

For answers, we interviewed Professor David Finkelhor. He runs the Crimes Against Children Research Center and has authored several books about child homicide, abductions and sexual abuse.

“Child kidnapping is a very rare phenomenon to start out with,” Finkelhor said. “We estimate that there are maybe 100 or so serious kidnappings of children in the United States (each year) … The most typical kind of kidnapping is of a teenage girl for the purposes of sexual assault,” Finkelhor said. “Sometimes — very rarely — [it’s] for the purposes of abducting them into sex trafficking, but even that is very rare.”

When it comes to younger children — like the ones described in the Highlands Ranch mom’s Facebook post — kidnappings are usually by a family member during a custody dispute.

“I think it’s more likely these are parents who are concerned about a person behaving suspiciously and go to the possibility that this is for reasons of abduction or sex trafficking…” Finkelhor said. “Sex trafficking has gotten a lot of attention lately, so perhaps they immediately went to that idea. But I don’t think that’s a very realistic scenario.”

Finkelhor’s theory is backed up by the law enforcement officials 9NEWS interviewed as part of the original verify on this Facebook post.

Beth Boggess, the FBI supervisory special agent who heads Colorado’s violent crimes against children unit, told 9NEWS that human traffickers tend to lure vulnerable teens over time.

“It’s a completely different crime,” Boggess said. “We don’t see kidnapping for human trafficking.”

Neither Boggess or the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office, which investigated this claim and a similar one in May, had heard of a single incident where a young child was kidnapped from a store for the purposes of sex trafficking.

And versions of this scenario have been debunked by other law enforcement officials across the country, including Michigan and California.

“This is a very unusual and perhaps implausible kind of abduction scenario,” Finkelhor said.

Time and again, those knowledgeable about sex trafficking and folklore plant viral posts such as the Lawrence claim in the realm of folklore, not credible crime warnings:

Police in Lawrence, Massachusetts have not yet addressed the Snapchat sex trafficking rumor despite its viral spread. However, it is highly unlikely given the wealth of knowledge and research into how sex and labor trafficking begins and continues.

Anti-trafficking organizations like the Polaris project offer information about the causes and methods of sex trafficking here.

Update, April 24 2019, 12:14 PM: Police in Lawrence, Massachusetts addressed the Snapchat sex trafficking rumor, asserting that there was “no substance” to the claim:

- BEWARE OF A SNAPCHAT SCAM THAT COULD BE LINKED TO SEX TRAFFICKING

- SCARY SNAPCHAT SCAM COULD BE LINKED TO SEX TRAFFICKING

- Study details link between social media and sex trafficking

- Police: Lincoln sex trafficking suspect met minor on Snapchat, told her to 'auction' herself

- Police arrest N.C. man on suspicion of attempted kidnapping after coming to Lincoln to meet 14-year-old girl

- HUMAN TRAFFICKING

- The Modern American Brag: “My Kids Were About to be Trafficked, Too!”

- VERIFY: Do child sex traffickers look for victims at the store?

- The Victims & Traffickers