On April 12 2023, an Imgur user uploaded a screenshot of a tweet asserting that workers in certain professions (logging, roofing, and sanitation among them) had “statistically more dangerous jobs” across the board than law enforcement officers:

Background and Context for the Tweet

Although the tweet appeared on Imgur in April 2023, it was originally posted on May 27 2022. Context for the “good a time” part was not immediately apparent, and the tweet simply read:

Seems as good a time as any to remind people that loggers, roofers, construction workers, sanitation workers, truckers, miners, agricultural workers, etc. all have statistically more dangerous jobs than cops—and if they refuse to do those jobs they get fired, not more money.

Based on the tweet’s date, it seemed to be referencing the May 24 2022 Uvalde school shooting in which nineteen students and two teachers were murdered at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas. More specifically, the tweet addressed what was at the time a developing news story — concerning the Uvalde police response, or more to the point, their lack of any response at all.

On the same date the tweet was published (May 27 2022), the Texas Tribune published “What we know, minute by minute, about how the Uvalde shooting and police response unfolded,” reporting in part:

Details of how long it took for officers to confront the shooter — about 1 hour and 15 minutes — have also sparked widespread outage and criticism. In July [2022, after publication], an investigation into the shooting by a Texas House committee determined the law enforcement response was plagued by “systemic failures and egregious poor decision making.”

On May 28 2022, the Associated Press published “Police inaction moves to center of Uvalde shooting probe,” providing details about initial focus on police inaction in Uvalde; the tweet alluded to workers who “refuse to do those jobs”:

The actions — or more notably, the inaction — of a school district police chief and other law enforcement officers have become the center of the investigation into this week’s shocking school shooting in Uvalde, Texas [on May 24 2022].

The delay in confronting the shooter — who was inside the school for more than an hour — could lead to discipline, lawsuits and even criminal charges against police.

The attack that left 19 children and two teachers dead in a fourth grade classroom was the nation’s deadliest school shooting in nearly a decade, and for three days [between May 24 and 27 2022] police offered a confusing and sometimes contradictory timeline that drew public anger and frustration.

By Friday [May 27 2022], authorities acknowledged that students and teachers repeatedly begged 911 operators for help while the police chief told more than a dozen officers to wait in a hallway at Robb Elementary School. Officials said he believed the suspect was barricaded inside adjoining classrooms and that there was no longer an active attack.

Reports from the week after the Uvalde shooting illustrated the public’s rapidly intensifying anger. On May 29 2022, CNN reported:

The decision by police to wait before confronting the gunman at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde was a failure with catastrophic consequences, experts say. When it was all over 19 students and two teachers were dead.

While 18-year-old Salvador Ramos was inside adjoining classrooms, a group of 19 law enforcement officers stood outside the classroom in the school for roughly 50 minutes as they waited for room keys and tactical equipment, CNN has reported. Meanwhile, children inside the classroom repeatedly called 911 and pleaded for help, Texas officials said.

Texas Department of Public Safety Col. Steven McCraw acknowledged errors in the police response to [the May 24 2022] mass shooting. The on-scene commander, who is also the Uvalde school district police chief, “believed that it had transitioned from an active shooter to a barricaded subject,” McCraw said.

“It was the wrong decision. Period. There’s no excuse for that,” McCraw said of the supervisor’s call not to confront the shooter.

A PBS.org article published on the same day, “Uvalde shooting investigation focuses on police response,” described an even longer delay. The outlet also addressed “damning” bodycam footage in a July 2022 report:

The actions — or more notably, the inaction — of a school district police chief and other law enforcement officers moved swiftly to the center of the investigation into this week’s shocking school shooting in Uvalde, Texas [on May 24 2022.]

The delay in confronting the shooter — who was inside the school for more than an hour — could lead to discipline, lawsuits and even criminal charges against police … The chief’s decision — and the officers’ apparent willingness to follow his directives against established active-shooter protocols — prompted questions about whether more lives were lost because officers did not act faster to stop the gunman, and who should be held responsible.

[…]

As the gunman fired at students, law enforcement officers from other agencies urged the school police chief to let them move in because children were in danger, two law enforcement officials said.

In October 2022, the New York Times covered an ongoing investigation into the actions of police in Uvalde, indicating that “scores of trained officers, including those from an elite Border Patrol unit, took many of the same steps” as local police on the scene. A February 2023 ABC News article (“‘No one took leadership’: A detailed look at the failings in Uvalde school shooting”) indicated the delay in response lasted 77 minutes (as did the Times):

What has remained largely obscured, however, is the story of why it took 77 minutes for any of the nearly 400 law enforcement officers assembled that day to confront the killer and bring the massacre to an end.

There are still few satisfying answers as of April 2023, nearly a year later.

Do ‘Loggers, Roofers, Construction Workers, Sanitation Workers … All Have Statistically More Dangerous Jobs Than Cops’?

An initial search for the May 2022 tweet led to a similar tweet from June 2020 (which included a chart):

Text at the bottom of the chart provided a source (the Washington Post‘s Wonkblog) and a date, 2013. In March 2023, USA Today published “What are America’s most dangerous jobs? Search our database of deadliest occupations,” and cited data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS):

Nearly 5,200 people died from injuries they suffered on the job in 2021. That is more than in 2020, when COVID-19 shutdowns and layoffs kept many people away from the workplace, but a bit less than the total a year before the pandemic set in.

The data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics provides a broad look at the risks faced by American workers … USA TODAY used the federal statistics to rank the most dangerous private-industry jobs in America. We’ve included the 25 occupations with the highest death rates in 2021 but provide the full rankings in our database. Fatal injury rates were calculated only for job titles held by at least 20,000 people and that reported at least four fatalities.

An attached list of jobs ranked by “deadliest” began with tree trimmers, commercial pilots, farm workers, loggers, and roofers. “Police” did not appear among the 25 deadliest jobs.

A February 2022 blog post by a law firm was one of the most prominent search results for “America’s most dangerous jobs.” The firm said that their list came from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), but we were unable to locate OSHA statistics directly.

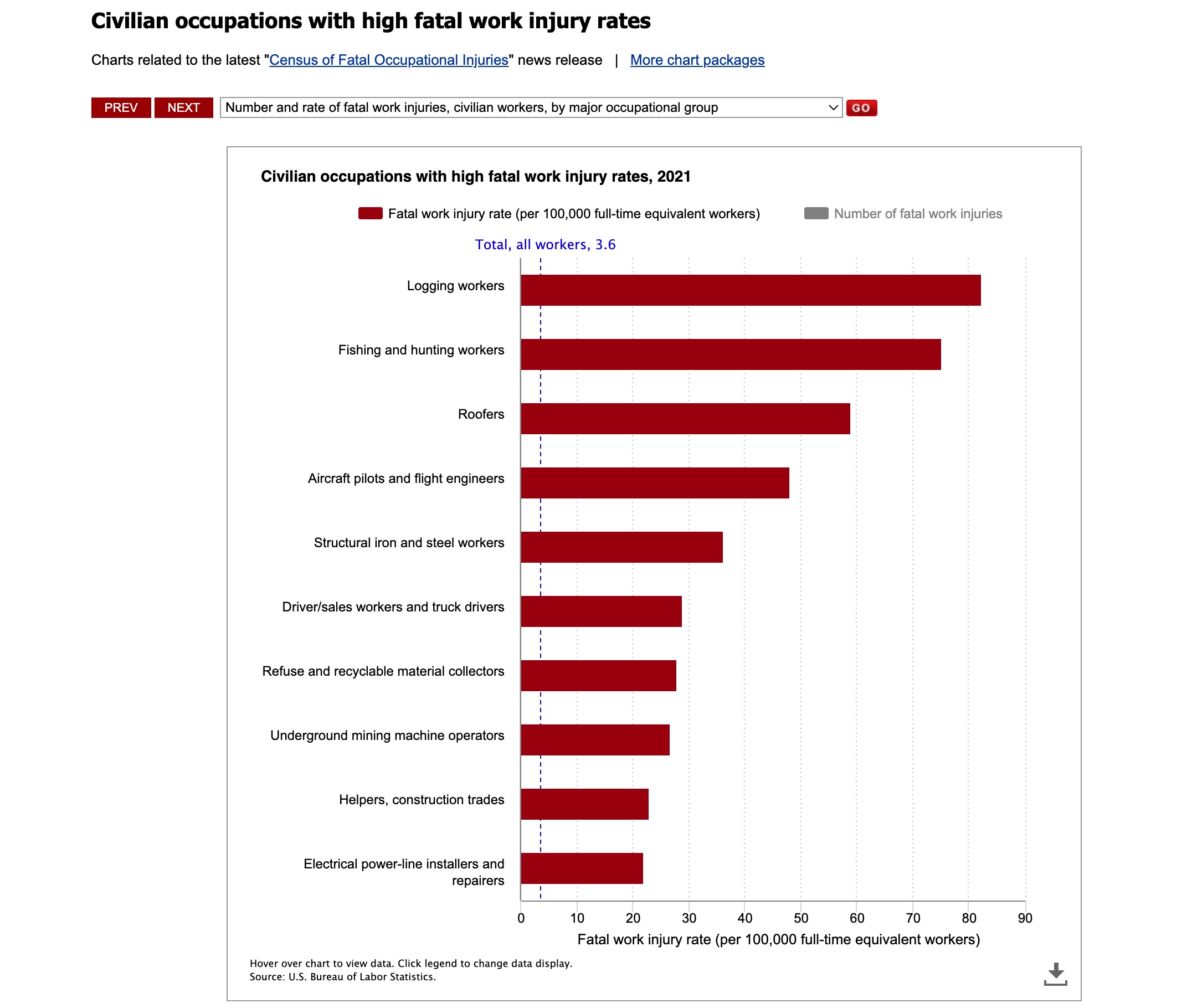

USA Today’s March 2023 article described statistics for 2021, suggesting that statistics were updated around 15 months after the end of a given calendar year. A search for BLS statistics on America’s “deadliest jobs” led to a “data tools” section on BLS.gov, landing on a chart labeled “Civilian occupations with high fatal work injury rates” for the year 2021:

That chart aligned with the list version by USA Today, but it specifically mentioned “civilian” occupations, possibly excluding law enforcement. On the dropdown menu, one available chart was labeled “Fatal occupational injuries by event or exposure,” listing the causes as “transportation injuries, falls/slips/trips, contact with objects and equipment, violence by persons or animals, exposure to harmful substances or environments, and fires/explosions.”

Yet another chart for “Number and rate of fatal work injuries, by private industry sector” was listed in the dropdown. In descending order, the trades were “construction, transportation and warehousing, agriculture, manufacturing, retail, leisure and hospitality, other services (exc. Public admin.), wholesale trade, educational and health services, and financial activities.”

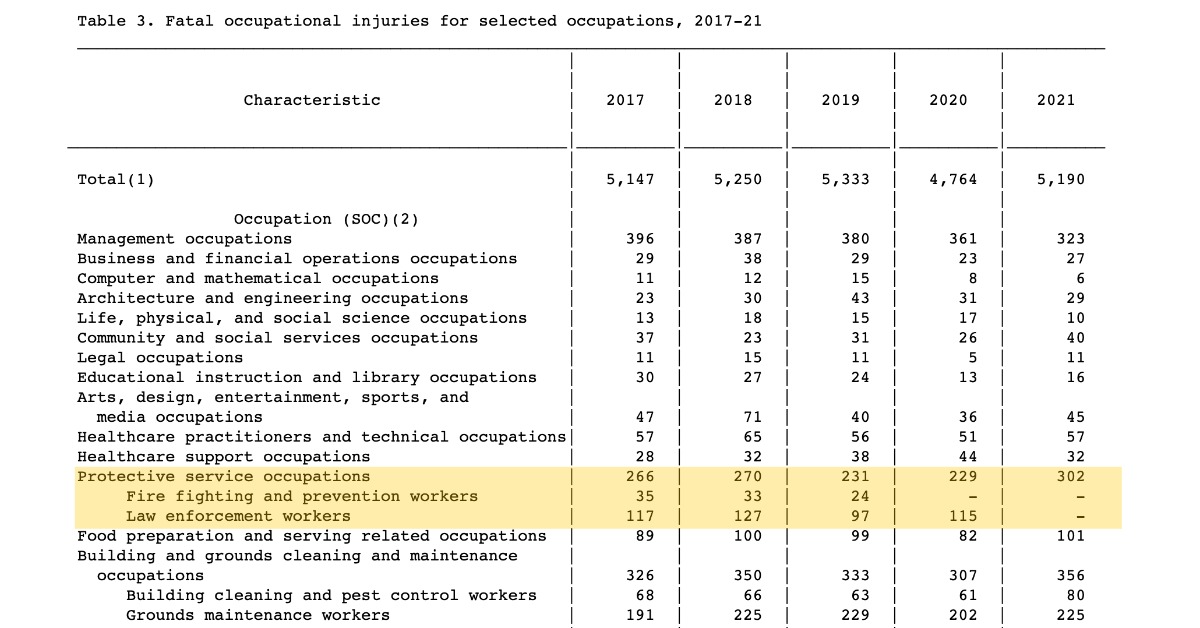

Finally, we located a December 16 2022 BLS news release, “Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary, 2021.” It grouped police and firefighters as “protective service occupations,” and the first mention of work-related fatalities appeared under “Occupation”:

Occupation

– There was a 16.3-percent increase in deaths for driver/sales workers and truck drivers which went up to 1,032 deaths in 2021 from 887 deaths in 2020. This was the primary factor behind the increase in fatalities to workers in transportation and material moving occupations which reached a series high in 2021.

– Construction and extraction occupations had the second most occupational deaths (951) in 2021, despite experiencing a 2.6-percent decrease in fatalities from 2020. The fatality rate for this occupation also decreased from 13.5 deaths per 100,000 FTE workers in 2020 to 12.3 in 2021.

– Protective service occupations (such as firefighters, law enforcement workers, police and sheriff’s patrol officers, and transit and railroad police) had a 31.9-percent increase in fatalities in 2021, increasing to 302 from 229 in 2020. Almost half (45.4 percent) of these fatalities are due to homicides (116) and suicides (21). About one-third (33.4 percent) are due to transportation incidents, representing the highest count since 2016.

– Installation, maintenance, and repair occupations had 475 fatalities in 2021, an increase of 20.9 percent. Almost one-third of these deaths (152) were to vehicle and mobile equipment mechanics, installers, and repairers.

– The fatal injury rate for fishing and hunting workers decreased from 132.1 per 100,000 FTEs in 2020 to 75.2 in 2021.

In that excerpt, the cumulative category of “protective service occupations” included 302 fatalities. By contrast, driver/sales workers and truck drivers had 1,032 fatalities, and installation/repair workers had 472 fatalities.

A copy of the news release with data tables included a table for “Fatal occupational injuries for selected occupations, 2017-21.” “Protective service occupations” lacked data for 2021, and data for the prior years in the sub-categories did not add up to the category’s sum:

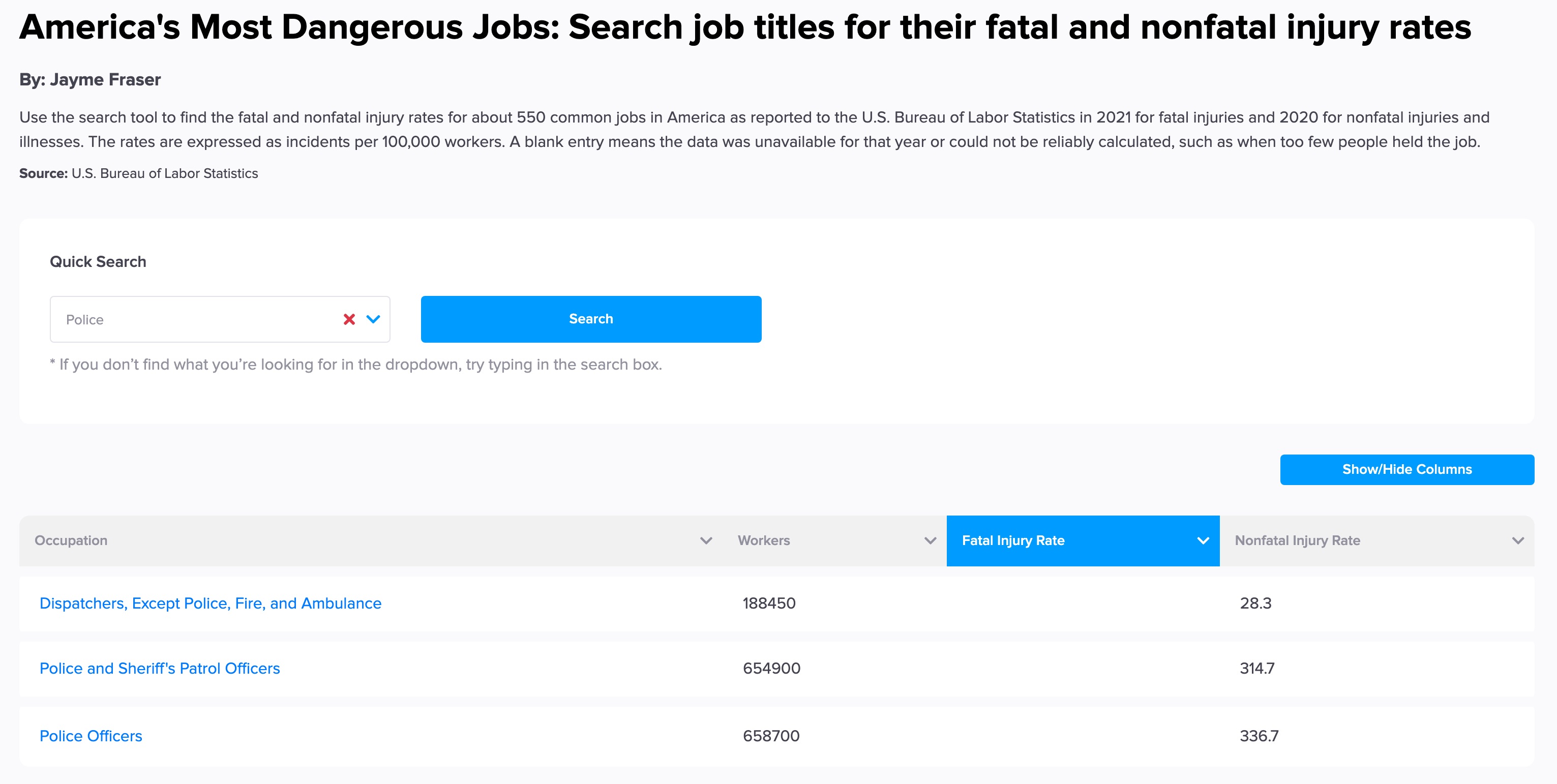

Finally, USA Today created an interactive database of “America’s Most Dangerous Jobs.” Its first page provided fatal injury rates from tree trimmers at the top (186.7 per 100,000 workers) down to plaster and stucco masons (22.24 per 100,000).

Police appeared on the list in three categories, with a blank column for rates of fatal injury:

A 2020 blog post from the University of Delaware’s facilities department ranked law enforcement at number 22, with a 2020 fatality rate of 14 per 100,000 people — fewer than the 22.24 for stonemasons. In May 2020, exam preparation service CivilServiceSuccess.com published “Common Myths About Law Enforcement Careers — Debunked,” making claims similar to the tweet in a recruitment context:

Myth #1: Law Enforcement Work is Extremely Dangerous

No one can deny the fact that police work is dangerous. That said, it is fairly interesting to note where police work ranks among the most dangerous occupations in the United States. According to data on fatal injury rates for 72 occupations from the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, police and sheriff’s patrol officers rank 18th on a list of top 25 dangerous jobs in the country. The rate of fatal injuries in 2017 among police officers was 12.9 per 100,000 workers. The total number of fatal injuries amounted to 95. The most common fatal accidents included violence and other injuries by persons or animals.

Grounds maintenance workers, general repair and maintenance workers, agricultural workers, farmers, ranchers, and drivers all ranked above police officers in terms of fatal injury rates and the total number of fatal injuries. The most dangerous occupation belongs to fishers and fishing-related workers, where there are were 100 fatal injuries per 100,000 workers. The second-most dangerous occupation belongs to logging workers, followed by airplane pilots and flight engineers.

Summary

In April 2023, a May 2022 tweet claiming that “loggers, roofers, construction workers, sanitation workers, truckers, miners, agricultural workers, etc. all have statistically more dangerous jobs than cops — and if they refuse to do those jobs they get fired, not more money” was shared as a screenshot to Imgur. Originally, the tweet was part of a national discussion about the Uvalde school mass shooting. Annual statistics compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics detailed the most dangerous jobs in America, routinely ranking logging, trucking, sanitation, and aircraft piloting as statistically far more dangerous professions than policing.

- Seems as good a time as any to remind people that loggers, roofers, construction workers, sanitation workers, truckers, miners, agricultural workers, etc. all have statistically more dangerous jobs than cops—and if they refuse to do those jobs they get fired, not more money. | Imgur

- Seems as good a time as any to remind people that loggers, roofers, construction workers, sanitation workers, truckers, miners, agricultural workers, etc. all have statistically more dangerous jobs than cops—and if they refuse to do those jobs they get fired, not more money. | Twitter

- What we know, minute by minute, about how the Uvalde shooting and police response unfolded

- Police inaction moves to center of Uvalde shooting probe

- Police failed to act quickly in Uvalde. Experts say their inaction allowed for the massacre to continue and led to catastrophic consequences

- Uvalde shooting investigation focuses on police response

- State Investigation Fueled Flawed Understanding of Delays During Police Response in Uvalde

- 'No one took leadership': A detailed look at the failings in Uvalde school shooting

- Damning report, bodycam video show chaos of police response to Uvalde shooting

- We should keep in mind that the job police do is very dangerous. Not as dangerous as loggers, or fishers, or roofers, or miners, or construction workers, or farmers, or salesmen, or taxi drivers, or ground maintenance workers. Still, it is slightly more dangerous than...umpires. | Twitter

- What are America’s most dangerous jobs? Search our database of deadliest occupations

- TOP 10 MOST DANGEROUS JOBS ACCORDING TO OSHA

- Civilian occupations with high fatal work injury rates | Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Fatal occupational injuries by event or exposure | Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Number and rate of fatal work injuries, by private industry sector | Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary, 2021 | Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary, 2021 | Bureau of Labor Statistics

- America's Most Dangerous Jobs

- 25 Most Dangerous Jobs

- Common Myths About Law Enforcement Careers—Debunked!