In January 2023, the death of Tyre Nichols at the hands of police in Memphis, Tennessee drew widespread outcry in the United States. Ditto for the death in Atlanta, Georgia that same month of protestor and environmental activist Tortuguita — Manuel Esteban Paez Teran — who law enforcement killed during protests over the site of a planned law enforcement training facility.

As public anger and unrest grew and spread, like clockwork, a perennial canard about the role of “outside agitators” re-emerged.

One January 27 2023 tweet simply warned people in Memphis to be mindful of agents of “chaos”:

But the phrase “out of town” appeared in several other tweets from that date, introducing the idea that protests in that city (and others) could only be the work of “outside agitators“:

Versions of that same concept came from Atlanta officials (and others):

Almost exclusively, mentions of people from “out of town” or “outside agitators” presented the concept as necessarily valid, frequently paired with a warning to avoid demonstrations completely for fear of their influence. A least one account deviated from that norm, tweeting about how effective that narrative can be:

The specter of “outside agitators” was not new in 2023 — the phrase has a storied, sordid history. It was perhaps accurate to say the concept gained further traction as part of ongoing discourse about police brutality, from the May 2020 death of George Floyd onward.

On the night of January 27 2023, a Memphis-area reporter quoted Shelby County District Attorney Steve Mulroy as warning about “outside agitators” at a press conference:

It was an oddly specific claim that is seemingly repeated without fail whenever citizens take to the streets to protest an injustice. In press conferences and on Twitter, police departments and elected officials commonly and confidently proclaimed that people from outside their jurisdiction were largely (if not wholly) responsible for all forms of unrest.

Regardless of individual iterations of the rumor, “outside agitators” as a purported phenomenon warrants inquiry; in a vacuum, the claim is odd and routine in equal measure. Why are protests so often attributed to shadowy figures, people consistently designated as “not from around here,” and how has the idea colored modern perceptions of civil rights-related movements?

‘Outside Agitators’ in 2020

After a night of unrest in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 29 2020 (in response to George Floyd’s murder), it was wholly predictable that “outside agitators” were blamed both by Gov. Tim Walz (D) and St. Paul Mayor Melvin Carter (D). As is often the case, few noticed that the claims were examined and found to be baseless:

Officials in Minnesota and Washington are claiming that outside groups are undermining the protests in Minneapolis, using them as a cover to set fires, loot stores and destroy property. But they disagree on whether far-left or far-right groups are to blame and have not offered evidence to substantiate their claims.

[In late May 2020], Governor Walz said the “best estimate” suggested that 80 percent of those arrested at the protests were not from the state. “I’m not trying to deflect in any way. I’m not trying to say there aren’t Minnesotans amongst this group,” Mr. Walz said. But “the vast majority,” he said, are from outside the state.

KARE, a Minneapolis television station, found that such claims may not be accurate. The station reviewed all of the arrests made by Minneapolis-based police agencies for rioting, unlawful assembly and burglary-related crimes from [May 29 2020] to [May 30 2020] and found that 86 percent of those arrested listed a Minnesota address.

The mayor of St. Paul, Melvin Carter, on [May 30 2020] retracted his claim that “every single person” arrested on[May 29 2020] was from out of state. A spokesman said the mayor later learned that “more than half” are from Minnesota.

In Carter’s statement, he emphatically claimed that “every single person” arrested was not just from out of town, but out of state. Walz echoed Carter, describing the “outside agitators” as the “vast majority” of those arrested.

After the September 2016 officer-involved shooting of Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, we sought to trace the folklore behind outside agitators to its origins. Here is what we found:

‘Outside Agitators’ in 2016 and 2014

The 20 September 2016 officer-involved shooting of Keith Lamont Scott led to widespread demonstrations in the city of Charlotte. During a CNN appearance on September 22 2016, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Fraternal Order of Police spokesman Todd Walther stated that the majority of protesters were bused in from other places.

Like Carter in 2020, Walther attributed a specific and similar percentage (70 percent to Carter’s 80 percent) of unrest to traveling, apparently professional agents of chaos:

This is not Charlotte that’s out here. These are outside entities that are coming in and causing these problems. These are not protestors, these are criminals … We’ve got the instigators that are coming in from the outside. They were coming in on buses from out of state. If you go back and look at some of the arrests that were made last night. I can about say probably 70% of those had out-of-state IDs. They’re not coming from Charlotte.

Walther’s statement (echoed in the contemporaneous use of the term “agitators” by CMPD in two tweets) caused a predictable stir on social media, holding that as many as seven out of ten people demonstrating in Charlotte were affiliated with “outside entities” and citing purported arrest records to back the claim up. Assertions that any and all large-scale protests were from “outside” were hardly novel or unique; the phenomenon was often blamed for altercations at Donald Trump’s campaign rallies:

Protests in Ferguson in 2014 were plagued by similar rumors, with Jewish billionaire (and frequent target of right-wing conspiracists) George Soros perennially named as the suspect purportedly masterminding the protests. Prior to Ferguson, the rumor was leveraged against pro-union protesters in Wisconsin in 2011 and Obamacare protesters or town hall attendees in 2009:

Even more interesting is the fact that the rumor is in no way exclusive to Soros’ purported plan to destabilize the United States via Black Lives Matter demonstrations; the Clinton campaign levied the charge at former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders after he won caucuses, and numerous examples from various other countries claim whichever side is “the opposition” is busing in fake objectors:

‘Outside Agitators’ in 20th Century America

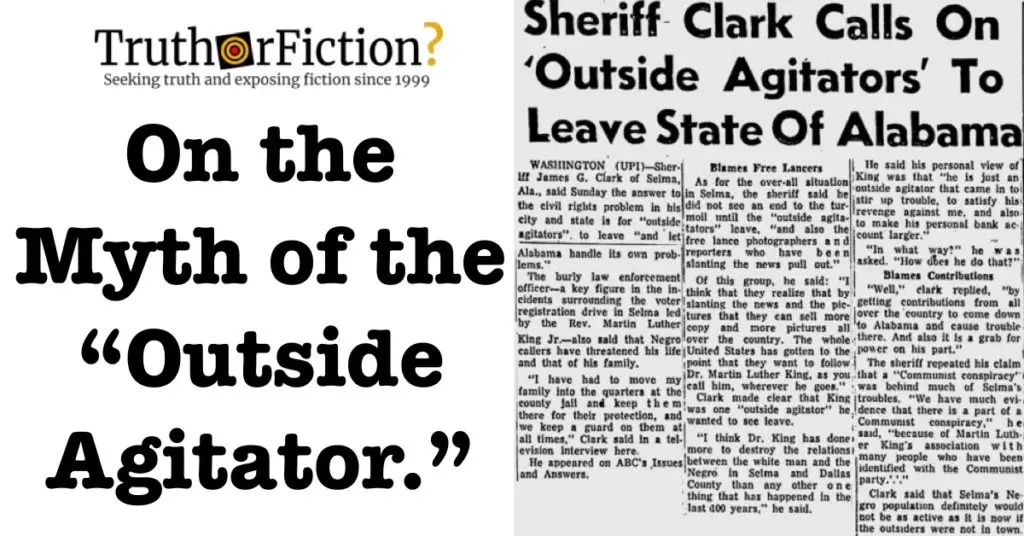

Ascribing civil rights protests to “outside agitators” far antedated social media. The phrase was entered into the Congressional Record on 12 March 1956, in a formal objection by Southern senators condemning the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education.

Notably, “outside agitators” served as something of a buffer in that context, delineating civil rights advocates as a group completely distinct from and inherently not representative of citizens affected by the ruling:

This unwarranted exercise of power by the court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the states principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through ninety years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding.

Without regard to the consent of the governed, outside agitators are threatening immediate and revolutionary changes in our public school systems. If done, this is certain to destroy the system of public education in some of the states.

With the gravest concern for the explosive and dangerous condition created by this decision and inflamed by outside meddlers.

That excerpted condemnation (“Southern Manifesto on Integration”) subsequently implored “our people” to resist provocation “by the agitators”:

In this trying period, as we all seek to right this wrong, we appeal to our people not to be provoked by the agitators and troublemakers invading our states and to scrupulously refrain from disorder and lawless acts.

One such out-of-town meddler took exception to the characterization a few years later — Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On 16 April 1963, King authored what would become the historically significant “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which he articulated the strategy behind labeling him an “outside agitator”:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” … I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in.” … Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here … Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

On 11 June 1963, Birmingham police chief George “Bull” Connor described King and associates as “outside agitator[s]” entirely at fault for civil disobedience in the city. Connor’s statement clearly implied King’s “side” of the controversy stood at odds with concerns of legitimate local citizens:

Ladies and gentlemen, for 42 days now the city of Birmingham has been under siege from outside agitators led by Martin Luther King. Now, the President has seen fit to move some 3,000 federal troops into this state for possible use in Birmingham … If the president is really sincere about wanting peace in Birmingham why doesn’t he use his great influence and ask Martin Luther King and his bunch of agitators to leave our city.

This bunch has done what they wanted to do, stir up trouble among whites and negro citizens, collected money, and have attempted to give this city a black eye to the rest of the nation. No sir, we don’t need federal troops here. What we need is for the president to show sincerity in wanting peace in Birmingham and get the outside agitators to leave us alone, and let us work out our problems locally. We will use the same tactics that we have used before.

The term was also invoked in 1964 by segregationist George Wallace in a letter to a “Ms. Martin,” in which he denied the presence of civil unrest save for the work of “outside agitators.” Wallace also posited that only the outside agitators wished to see an integrated society, and no one else supported that cause:

Despite growing conflict over race and civil rights, Wallace wrote Martin that “we have never had a problem in the South except in a few very isolated instances and these have been the result of outside agitators.” Wallace asserted that “I personally have done more for the Negroes of the State of Alabama than any other individual,” citing job creation and the salaries of black teachers in Alabama. He rationalized segregation as “best for both races,” writing that “they each prefer their own pattern of society, their own churches and their own schools.” Wallace assured Martin that Alabamans were satisfied with society as it was and that the only “major friction” was created by “outside agitators.” Increasing racial violence and the Civil Rights Movement, however, pointed toward a changing equilibrium in race relations in Alabama.

In August 1964, outside agitators were blamed for unrest in Philadelphia. Repeating the ongoing pattern, outside agitators were again identified by local authorities as responsible for civil rights-related unrest in Los Angeles in 1965, as well as concurrent protests in Alabama.

If a common thread existed in these repeated claims, it was a lack of plausible explanation as to who or what grouped and dispatched the agitating parties to various locations across the United States. Law enforcement agencies and politicians addressing the public with respect to demonstrations and similar incidents simply painted those involved as part of a shadowy network of “others” whose presence threatened the peace wherever protests or riots occurred.

Little was heard about outside agitators between the civil rights movement of the 1960s and the 2000s (when the belief was dusted off and fell back into favor), save for a 1988 study which determined if such entities indeed existed, they were unlikely to entice moderate local activists to engage in radical action. But by 2008, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) documented a reappearance of the concept in Selma during a contemporaneous controversy:

Nowadays, some of Selma’s old-school racists aren’t that old. Last May [2007], a group of high school students at Morgan Academy formed an online Facebook social networking group to protest the Freedom Foundation. The group was called “Go Back to Colorado.”

One of the first posts, dated May 4 [2007], was short and to the point: “Those damn n***** lovers can kiss my country ass!!”

White supremacist organizations are paying increasing attention to the Freedom Foundation’s controversial efforts. History is repeating itself in Selma. Even the epithets are the same: Troublemakers. Outside agitators. N***** lovers.

Summary

The enduring legend of the outside agitator has existed since at least 1956, and its original meaning remained remarkably intact when a police brotherhood spokesman blamed unrest in Charlotte on the purported mass busing-in of “instigators” during a CNN appearance on 22 September 2016. At that time, the public seemed content to accept the explanation as credible and logical despite a lack of any corroborating historical or contemporaneous evidence; Soros was the only figure cohesively fingered for fomenting imaginary dissent in a half-century of outside agitator rumors (though “Communists” sometimes were credited for the propping up of protests).

Another facet of the rumor was the insistence that paid protesters arrived on buses; without that detail, the implication that larger and more sinister forces were at play wasn’t nearly as palpable. Outside agitators could, after all, act of their own free will on purely conscience-based grounds, as described by Martin Luther King, Jr. But the introduction of buses insinuated that a bigger conspiracy was driving any and all civil disruptions.

Were outside agitators a genuine contributing factor to any unrest, surely some evidence would have emerged linking these surreptitious efforts to a cabal of sorts, given their ever-present pall over civil rights disputes over more than fifty years. When the rumor was lobbed against unions in Florida in 2011, PolitiFact investigated the claim and found it to be false. Outside agitators were blamed for unrest in Ferguson in 2014, but police later confirmed the bulk of protesters arrested during that event were from the St. Louis area.

Baltimore mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake trotted the claim out during 2015 protests after the death of Freddie Gray, but records indicated that only three of 31 people arrested during protests in the city were not from the area.

And as for Charlotte in 2016, Walther firmly maintained that upwards of 70 percent of arrestees taken into custody at the protest were “instigators” arriving on “buses from out-of-state.”

But comments on a clip of the segment told a different story, linking to a Charlotte Observer article published on the same date Walther made the claim to a national audience on CNN. The paper completely shattered the claim, reporting:

Most of the people arrested by Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police [in 2016] during the sometimes violent protests uptown were from Charlotte, and most did not have criminal records.

The Observer reviewed CMPD arrest reports between midnight and 2 a.m. [the night of the arrests]. There were 31 people arrested for failure to disperse, six people arrested for breaking and entering, one for assault on a government official; two for larceny after break-in; two for resisting an officer and disorderly conduct; and one arrest for larceny and injury to property.

Of those 42 people arrested, 32 live in Charlotte, according to their arrest records. The others mostly live nearby, in Albemarle, Gastonia, Greensboro and Raleigh.

We contacted the CPMD in 2016 to ask about Walther’s claim, but our calls and emails were never returned. We also reached out to the SPLC at that time to ask about the role of the “outside agitators” myth, with respect to the civil rights movement and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Senior Fellow Mark Potok confirmed that the myth of “outside agitators” was a “propaganda scam” consistently used to delegitimize genuine localized dissent:

Nine times out of 10, when local officials complain about ‘outside agitators’ stirring up trouble in their communities, what they really are objecting to is that local people have actually risen up in response to their very real oppression. This bogus claim has been leveled at Martin Luther King Jr., the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and just about every other organization fighting for social justice. It is a propaganda scam, aimed at pointing the finger of blame precisely where it does not belong.

Much like the Black Lives Matter movement itself, the myth of outside agitators (largely advanced by police departments, lawmakers, and segregationists) originated with the civil rights movement. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., now a figure of largely undisputed acclaim, was consistently described as an outside agitator by authorities and opponents of integration in Birmingham during acts of civil disobedience in 1963 and 1964. Invariably, large acts of dissent (particularly race-related) conjure up tales of the same invisible, powerful cabal sending paid protestors on buses to manufacture chaos in a variety of locations that would otherwise (it is heavily implied) remain peaceful.

But time and again, both in research and by records, data demonstrates that protests and demonstrations are largely the work and dominion of the communities in which they occurred, not a network of paid for and bused-in disruptors causing havoc for a larger and more nefarious purpose. And aside from the fact that we hear new references to “outside agitators” every year, nothing that has taken place since Ferguson has done anything to change our understanding of the phrase, or its underlying meaning.

- Death of Tyre Nichols | Wikipedia

- Memphians: Please be weary of outside agitators who'd like to use this tragedy to stir chaos and tear up the city. Folks are fomenting violent protest from as far away as Arizona. | Twitter

- 2020–2022 United States racial unrest

- DA mulroy: if any outside agitators plan to not protest peacefully… he says you’re making it about you and not Tyre Nichol’s or police reform | Twitter

- Fiery Clashes Erupt Between Police and Protesters Over George Floyd Death

- Minnesota governor and mayors blame out-of-state agitators for violence and destruction

- Shooting of Keith Lamont Scott

- Criminals, Terrorists, and Outside Agitators: Representational Tropes of the ‘Other’ in the 5 July Xinjiang, China Riots

- The only 'outside agitators' left in Ferguson are the white cops who don't live here

- Five myths about riots

- Southern Manifesto on Integration (March 12, 1956)

- "Letter from a Birmingham Jail [King, Jr.]"

- Bull Connor Statement

- George Wallace on segregation, 1964

- DA attributes rioting to 'outside agitators

- Watts Riots

- “Outside Agitators” and Crowds: Results from a Computer Simulation Model

- ACTIVISTS CONFRONT HATE IN SELMA, ALA.

- Says "union bosses" bused protesters to a Central Florida education protest.

- No, ‘outside agitators’ have not been dominating the unrest in Ferguson