A February 21 2021 Facebook post about the purported origins of the “peace sign” or “peace symbol” was popular almost immediately. The post stated that the hand sign was conceived on that date in 1958 by a British graphic designer and pacifist:

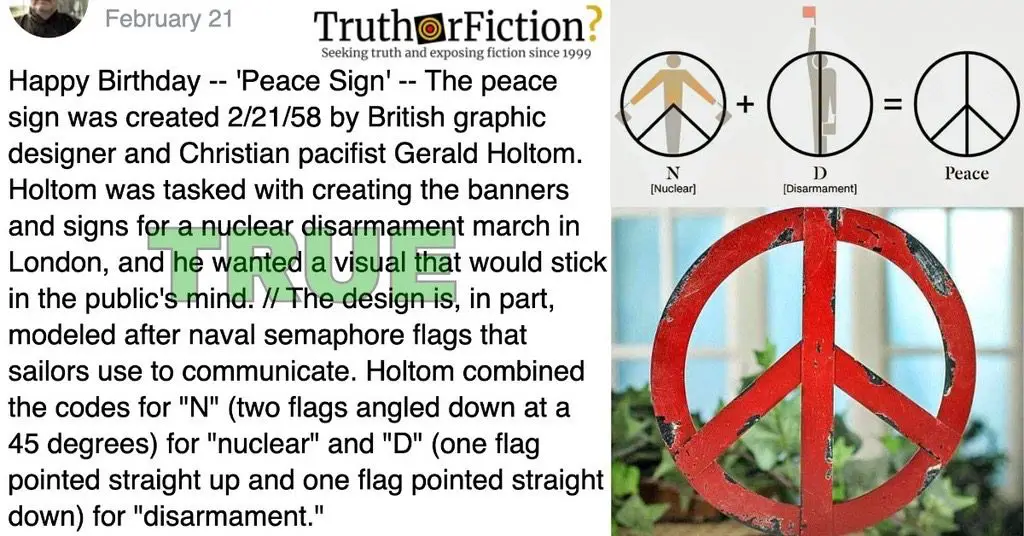

Alongside an image of the peace sign and an illustrated breakdown of its purported elements, the author wrote:

Happy Birthday — ‘Peace Sign’ — The peace sign was created 2/21/58 by British graphic designer and Christian pacifist Gerald Holtom. Holtom was tasked with creating the banners and signs for a nuclear disarmament march in London, and he wanted a visual that would stick in the public’s mind. // The design is, in part, modeled after naval semaphore flags that sailors use to communicate. Holtom combined the codes for “N” (two flags angled down at a 45 degrees) for “nuclear” and “D” (one flag pointed straight up and one flag pointed straight down) for “disarmament.”

That post was shared more than 40,000 times in two days, hinting that few readers had been aware of the symbol’s origins and meaning:

Wow! I never heard the part about the semaphore signal relationship.

Another recalled:

I remember this being an extremely controversial symbol in the 50s. You could get punched out for being a “commie.”

A Wikipedia page for “Peace symbols” (in general) identified the glyph (☮️) as the most well-recognized of all known symbols for peace, and an introductory paragraph alluded to the specific origins described in the viral Facebook post, which is perhaps where they got their information to begin with:

A number of peace symbols have been used many ways in various cultures and contexts. The dove and olive branch was used symbolically by early Christians and then eventually became a secular peace symbol, popularized by a Dove lithograph by Pablo Picasso after World War II. In the 1950s the “peace sign”, as it is known today, was designed by Gerald Holtom as the logo for the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), a group at the forefront of the peace movement in the UK, and adopted by anti-war and counterculture activists in the US and elsewhere.

A short, undated entry on Brittanica‘s “Demystified” indicated the peace sign was falsely rumored to be “a Satanic character,” and “a Nazi emblem”:

Thankfully, the [peace sign] has a clear history, and its origin is not so controversial. The modern peace sign was designed by Gerald Holtom for the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1958. The vertical line in the center represents the flag semaphore signal for the letter D, and the downward lines on either side represent the semaphore signal for the letter N. “N” and “D”, for nuclear disarmament, enclosed in a circle.

A November 2017 article about the origins of the peace sign published in The Week offered a section that provided a similar explanation, but with more detail about Holtom’s artistic inspiration:

The peace sign was created in 1958 by British graphic designer and Christian pacifist Gerald Holtom. Holtom was tasked with creating the banners and signs for a nuclear disarmament march in London, and he wanted a visual that would stick in the public’s mind.

The design is, in part, modeled after naval semaphore flags that sailors use to communicate. Holtom combined the codes for “N” (two flags angled down at a 45 degrees) for “nuclear” and “D” (one flag pointed straight up and one flag pointed straight down) for “disarmament.” But in a 1973 letter to the editor of Peace News, Holtom suggested the inspiration was also darker and more personal.

“I was in despair. Deep despair,” he wrote, according to the book TM: The Untold Stories Behind 29 Classic Logos. “I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalized the drawing into a line and put a circle round it. It was ridiculous at first and such a puny thing.”

Holtom’s commentary referenced Francisco Goya’s 1814 painting The Third of May 1808, which depicts a man with his arms raised upwards in surrender. In Holtom’s symbol, the stance is inverted, with its “arms” directed downward rather than upward:

The Third of May 1808 is set in the early hours of the morning following the [Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s armies during the occupation of 1808 in the Peninsular War] and centers on two masses of men: one a rigidly poised firing squad, the other a disorganized group of captives held at gunpoint. Executioners and victims face each other abruptly across a narrow space; according to Kenneth Clark, “by a stroke of genius [Goya] has contrasted the fierce repetition of the soldiers’ attitudes and the steely line of their rifles, with the crumbling irregularity of their target.” A square lantern situated on the ground between the two groups throws a dramatic light on the scene. The brightest illumination falls on the huddled victims to the left, whose numbers include a monk or friar in prayer. To the immediate right and at the center of the canvas, other condemned figures stand next in line to be shot. The central figure is the brilliantly lit man kneeling amid the bloodied corpses of those already executed, his arms flung wide in either appeal or defiance. His yellow and white clothing repeats the colors of the lantern. His plain white shirt and sun-burnt face show he is a simple laborer.

In 2014, Fast Company’s “The Untold Story of the Peace Sign” described the global adoption of the symbol (“internationally it has taken on a broader message signifying peace”), as well as some of its original nuance that had been lost in its rendering:

The symbol itself became more formalized as its usage became more widespread. The earliest pictures of Holtom’s design reproduce the submissive “individual in despair” more clearly: the symbol is constructed of lines that widen out as they meet the circle, where a head, feet and outstretched arms might be. But by the early 1960s the lines had thickened and straightened out and designers such as Ken Garland, who worked on CND material from 1962 to 1968, were able to use a bolder incarnation of the symbol in their work.

[…]

[Holtom] realized, [Professor Andrew] Rigby writes, that if he inverted the symbol “then it could be seen as representing the tree of life, the tree on which Christ had been crucified and which, for Christians like Gerald Holtom, was a symbol of hope and resurrection. Furthermore, that inverted image of a figure with arms stretched upwards and outwards also represented the semaphore signal for U–Unilateral.”

A 2019 CNN article about the peace sign’s origin, adoption, and evolution provided further context about the symbol’s enduring popularity and nascent form:

“It’s a minor masterpiece with major evocative power,” said design guru and cultural critic, Stephen Bayley, in an email. “It speaks very clearly of an era and a sensibility.

“It is, simply, a fine period piece: the ordinary thing done extraordinarily well.”

[…]

Ken Kolsbun, a peace symbol historian, believes the design’s simplicity played a role in its continued success. “You can have a 5-year-old draw it,” he said in a phone interview. “It’s such a powerful symbol with a sort of hypnotic appeal.”

Kolsbun has spent decades photographing the symbol, starting in the 1960s in California. “It came at the right time,” he said. “It also kept adapting, like a chameleon, taking on many different meanings for peace and justice.

“It’s an amazing design. Big corporations would die for something like this — just look at how many have their logos in a circle. Not surprisingly, some people draw it incorrectly, without the bottom line, and unwittingly draw the Mercedes logo.”

That profile also traced the peace sign’s migration from that 1958 march in London to a burgeoning counterculture movement in the United States, crediting the civil rights movements for introducing the symbol to Americans via a participant in both the movement in the U.S. and the event in the UK.

Likewise, CNN identified an early opponent of the symbol — the far-right John Birch Society, whose racist and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories are still used as disinformation today:

In the US, the symbol was first used by the civil rights movements. It was probably imported by Bayard Rustin, a close collaborator of Martin Luther King Jr., who had participated in the London march in 1958. Crossing the Atlantic, the symbol lost its association with nuclear disarmament and came to signify, more generally, peace: “In the 1960s in the US, it was mainly anti-war,” said Kolsbun. “I didn’t even know it meant nuclear disarmament.”

As the Vietnam War escalated in the mid-1960s, the peace symbol was adopted by anti-war protesters and the counterculture movement, finding its stereotypical place on Volkswagen buses and acid-wash T-shirts. Intentionally kept free from copyright, it traveled far and wide, appearing in the former Czechoslovakia as a symbol against Soviet invasion, and in South Africa to oppose Apartheid.

As the symbol grew in popularity, it also faced opposition. “Some really hated (it), like the far-right group John Birch Society,” said Kolsbun. “They put out a monthly magazine and, in 1969, they did a story denouncing the symbol, saying that it was a sign of the devil. It ended up all over America and the New York Times picked up on it. It got so much publicity that some people still see it as satanic sign after all these years.”

In sum, the Facebook post accurately conveyed the origin and initial meaning behind the still-common peace sign — “in part, modeled after naval semaphore flags that sailors use to communicate.” Gerald Holtom blended semaphore signals for “N” (nuclear) and “D” (disarmament) to create the design. Its widespread adoption and rapid spread led to backlash and falsehoods about it being a “Satanic” sign, but as Brittanica’s explanation observed, the design “has a clear history, and its origin is not so controversial.”

- Happy Birthday -- 'Peace Sign' -- The peace sign was created 2/21/58 by British graphic designer and Christian pacifist Gerald Holtom. Holtom was tasked with creating the banners and signs for a nuclear disarmament march in London, and he wanted a visual that would stick in the public's mind. // The design is, in part, modeled after naval semaphore flags that sailors use to communicate. Holtom combined the codes for "N" (two flags angled down at a 45 degrees) for "nuclear" and "D" (one flag pointed straight up and one flag pointed straight down) for "disarmament."

- Peace symbol | Origin

- Where Did the Peace Sign Come From?

- The origin story of the peace sign

- Goya, Third of May, 1808

- The Third of May 1808

- The Untold Story Of The Peace Sign

- Three lines and a circle: A brief history of the peace symbol