Sinead O’Connor had a short but storied life. When the Irish musician and performer (who since 2018 had called herself Shuhada’ Sadaqat after converting to Islam) — died on July 26 2023, her groundbreaking Saturday Night Live performance was commonly referenced amid the tributes.

The Sinéad O’Connor Reddit Post, and Search Interest

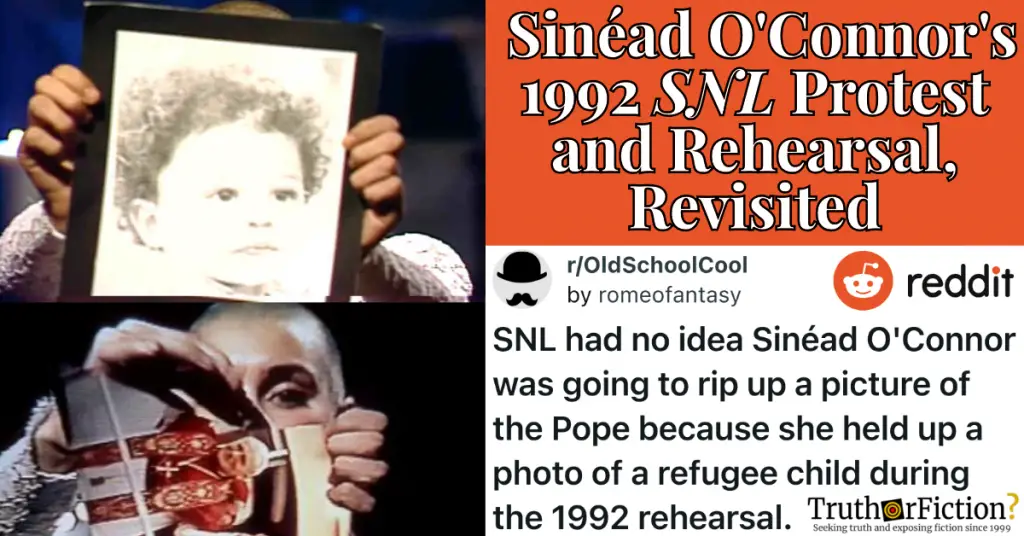

A post to Reddit’s r/OldSchoolCool on July 27 2023 featured a two-panel image of O’Connor, purportedly during a rehearsal before her 1992 SNL appearance. At the end of O’Connor’s live performance, she famously tore a photograph of Pope John Paul II to pieces:

In the post’s title, submitter u/romeofantasy claimed that “SNL had no idea Sinéad O’Connor was going to rip up a picture of the Pope because she held up a photo of a refugee child during the 1992 rehearsal.” However, the post consisted solely of the image, and did not link to anything supporting the titular claim.

Reverse image search on two separate platforms only matched the lower half’s image, of O’Connor tearing a photograph of Pope John Paul II. We were unable to locate any iterations of the top image — which appeared to depict O’Connor holding a framed photograph of a small boy.

Google Trends data showed a marked spike in interest in O’Connor’s 1992 SNL appearance. A search for “SNL” in the previous 24 hours returned searches with “Breakout” levels of interest, including: “Sinead on SNL,” “Sinead O Connor,” Sinead OConner SNL,” “SNL pope picture,” and “Sinead OConnor Pope.”

Sinéad O’Connor’s 1992 SNL Performance and Archival News Coverage

Sinéad O’Connor became internationally famous after the release of her version of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” in early 1990.

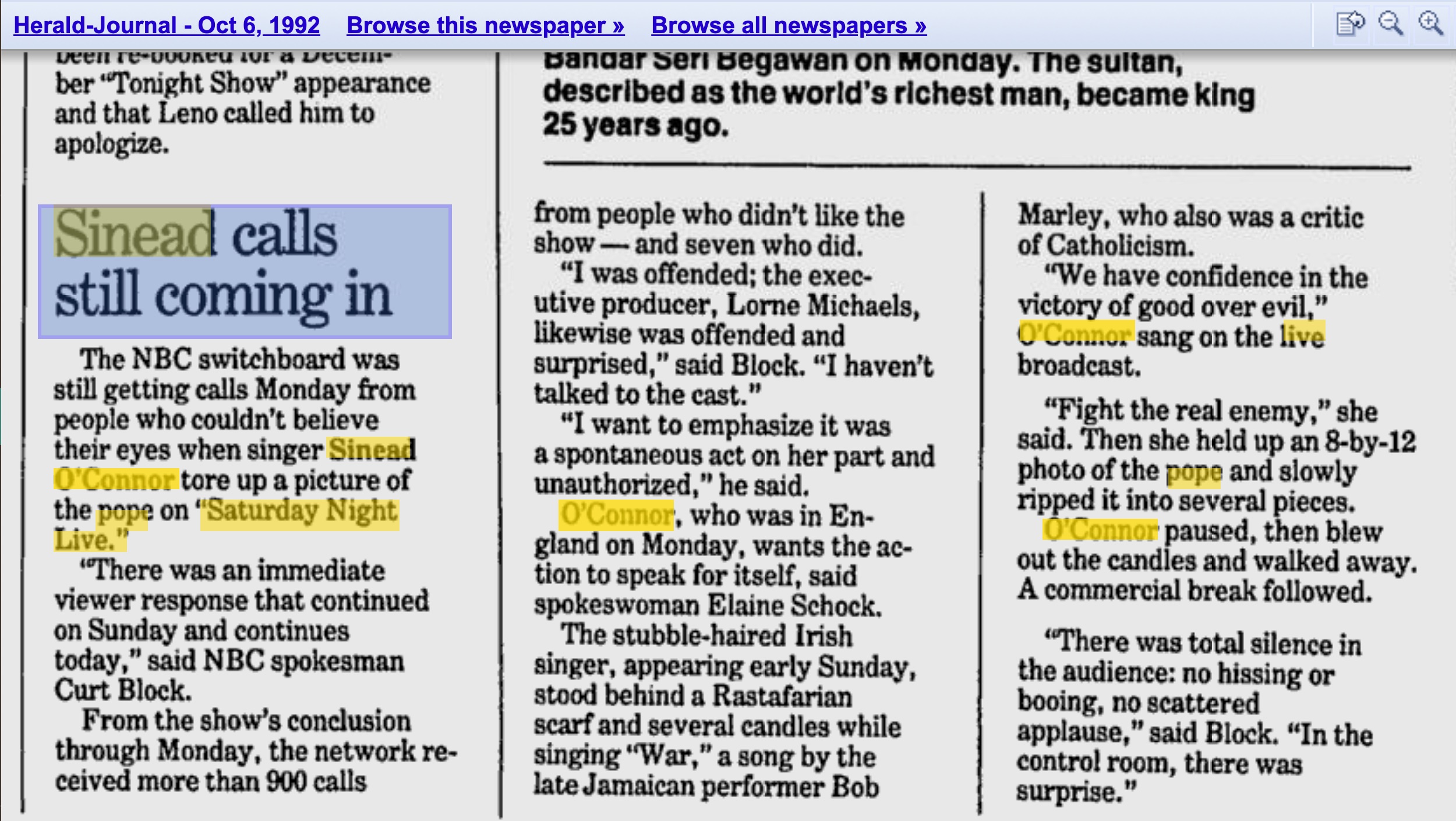

O’Connor was Saturday Night Live’s “musical guest” on October 3 1992. At the end of her set, O’Connor held up a photograph of Pope John Paul II and ripped it live on camera — a brief act that had tremendous ripple effects on her career and legacy.

A search of the New York Times archive for O’Connor’s name from 1991 through 1993 returned a small number of brief mentions of the incident in October 1992. Taken together, the string of published materials provided a retrospective view of how O’Connor’s protest was reported at that time; it primarily focusing on what she did, and rarely addressed why she did it.

An article dated October 5 1992 reported:

SINEAD O’CONNOR, the Irish singer, displayed a photograph of POPE JOHN PAUL II and tore it to bits during a live television appearance yesterday [October 3 1992].

The event occurred after an a capella song about racism, class differences, child abuse and other topics on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live.”

Wearing a long white gown and a Star of David pendant, she sang, “We have confidence in the victory of good over evil.”

Then she stated, “Fight the real enemy,” held up the 8-by-12 color photo and slowly ripped it into several pieces. As the studio audience watched in silence, The Associated Press reported, she paused, then blew out several candles and walked away.

A similar item dated October 12 1992 concerned the following week’s guest, Joe Pesci, and it quoted Pesci’s assertion that he “would have gave her such a smack”:

Remember that photo of POPE JOHN PAUL II that the singer SINEAD O’CONNOR ripped up on “Saturday Night Live” a week ago [in October 1992]? It’s back together again, at the request of last Saturday’s host, the actor JOE PESCI.

“Sinead O’Connor tore up a picture of the Pope and I thought that was wrong,” Mr. Pesci said at the start of the show. He held up the patched-up photo, to the audience’s applause.

The singer said she was protesting religious oppression. Mr. Pesci said that if it had been his show, “I would have gave her such a smack.”

An October 20 1992 column mentioned the ongoing controversy, reporting that O’Connor was publicly disinvited from an Irish culture-related event in New York City for her action:

More fallout from the furor caused by SINEAD O’CONNOR when she ripped up a photograph of the Pope on “Saturday Night Live” two weeks ago. MARY McFADDEN announced yesterday that she is rescinding an invitation to the Irish singer for the showing of her spring and summer collection at the New York Public Library on Nov. 5 [1992].

“It is with some regret that I must publicly ask Sinead O’Connor not to attend the debut of my collection dedicated to the ‘Book of Kells,’ ” Miss McFadden said. “While this fashion collection is based on the ancient religious manuscripts of Miss O’Connor’s homeland, it has become inappropriate for her to attend in light of her recent action of disrespect toward the leader of the Roman Catholic Church.”

On October 26 1992, another brief item described a protest in support of O’Connor’s act and “her efforts to expose the Catholic hierarchy as agents of oppression and to say that there are many, many people who stand with her in this”:

SINEAD O’CONNOR, the Irish rock singer who has come under attack for tearing up a picture of Pope JOHN PAUL II, received some support [on October 25 1992] from a group that staged a demonstration in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral during which some group members also tore up pictures of the Pope.

“We are here to demonstrate our support for Sinead O’Connor in her efforts to expose the Catholic hierarchy as agents of oppression and to say that there are many, many people who stand with her in this,” MARY LOU GREENBERG, one of the demonstrators, told The Associated Press.

Ms. O’Connor has said her action, which took place on “Saturday Night Live,” was intended to draw attention to child abuse, which she believes stems in part from the teachings of the Catholic Church.

On November 1 1992, the New York Times published “Why Sinead O’Connor Hit a Nerve.” It diverged from the concise scattered articles and columns, but still painted O’Connor as hysterical and dramatic; it began:

You think it’s easy to get booed at Madison Square Garden? Maybe it is for a visiting hockey team, but at a rock concert, drawing boos qualifies as a perverse kind of achievement. Sinead O’Connor, who was booed (as well as cheered) at the Bob Dylan tribute on Oct. 16 [1992], once again showed that she has a gift that’s increasingly rare: the ability to stir full-fledged outrage. She has stumbled onto the new 1990’s taboo: taking on an authority figure.

O’Connor was booed because, 13 days earlier, she had torn up a photograph of Pope John Paul II on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live,” saying, “Fight the real enemy.” Compounding her impropriety, she dropped her scheduled Dylan song and reprised “War,” the anti-racism song by Bob Marley and Haile Selassie. Her expression was timorous, defiant, martyred, and she made all the late-edition newspapers and television news.

Meanwhile, the tabloids happily reported, Madonna (no stranger to recontextualized Christian symbols) told The Irish Times: “I think there is a better way to present her ideas rather than ripping up an image that means a lot to other people.” She added, “If she is against the Roman Catholic Church and she has a problem with them, I think she should talk about it.”

She did: [In October 1992], O’Connor released an open letter, linking her being abused as a child to “the history of my people” and charging, “The Catholic church has controlled us by controlling education, through their teachings on sexuality, marriage, birth control and abortion, and most spectacularly through the lies they taught us with their history books.” The letter concluded, “My story is the story of countless millions of children whose families and nations were torn apart for money in the name of Jesus Christ.” Proselytizing as imperialism as child abuse — quite a leap.

From there, the author continued in the same vein, accusing Madonna of “professional jealousy” over O’Connor’s protest. Later in the article, O’Connor’s then-latest album was described as “a terrified child who believes every unhappy word,” and its concluding paragraphs read in part:

Yet for all O’Connor’s sincerity — and I don’t doubt that she means everything she blurts — she also has superb opportunistic reflexes; she hits nerves almost despite herself. She has achieved wide recognition, though notoriety doesn’t seem likely to pay off for her. Even her most ardent fans are likely to be disgusted by some of her statements in the current issue of Rolling Stone, like her contention that Mike Tyson was used by the woman he raped.

[…]

From O’Connor’s follow-up letter, it’s clear that she has the attitude that afflicts all post-Romantic artists: the conviction that her private problems are the world’s concern. From the unwillingness or inability to distinguish between private torments and public affairs come great statements and petty ones, raw nuttiness and carefully honed masterpieces. It’s easy to disagree with O’Connor’s latest outbursts. But better the occasional passionate, off-the-wall eruption — taking the chance that might stir up outrage — than a culture of safety and calculation.

That article twice referenced an open letter published by O’Connor in October 1992 explaining her actions. A Google search for one excerpt (““My story is the story of countless millions of children whose families and nations were torn apart in the name of Jesus Christ”) returned only 14 results.

Sinéad O’Connor’s October 1992 Open Letter, Why She Protested on SNL, and Additional Context

One result was dated October 24 1992, and included the full text of O’Connor’s open letter, which read:

Dear whoever,

My name is Sinead O’Connor. I am an Irish woman. And I am an abused child. The only reason I ever opened my mouth to sing was so that I tell my story and have it heard.

The cause of my abuse is the history of my people, whose identity and culture were taken away from them by the British with full permission from The “Holy” Roman Empire. Which they gave for money and in the name of Jesus Christ.

The only hope for me as an abused child was to look back into my childhood and face some very difficult memories and some desperately painful feelings and a lot of very tricky conversations! I had to have it acknowledged what was done to me so that I could forgive and be free.

So, it has occurred to me that the only hope of recovery for my people is to look back into our history. Face some very difficult truths and some very frightening feelings. It must be acknowledged what was done to us so we can forgive and be free.

If the truth remains hidden then the brutality under which I grew up will continue for thousands of Irish children. And I must by any means necessary WITHOUT the use of violence prevent that happening because I am a Christian.

Child abuse is the highest manifestation of evil. It is the root and effect of every addiction. Its presence in a society shows that there is not contact with God. And God is truth to me.

The Catholic Church have controlled us by controlling education. Through their teachings on sexuality, marriage, birth control and abortion. And most spectacularly through the lies they taught us with their history books.

The story of my people is the story of the African people, the Jewish people, the Amer-Indian people, the South American people.

My story is the story of countless millions of children whose families and nations were torn apart for money in the name of Jesus Christ.

God IS Truth.

SINEAD O’CONNOR

In July 2023, O’Connor’s words appeared to speak directly to what is now known as the “Catholic Church abuse scandal,” a wide-ranging and by now, well-documented pattern of worldwide abuse — which largely came to light in the years immediately following O’Connor’s protest.

“Timeline” style coverage of the Catholic Church abuse scandal was not consistent with respect to exactly when the matter came to light, and much of it was recently published with the benefit of hindsight. An April 2010 NPR article, “Timeline: Priest Abuse Claims Date Back Decades,” described scattered cases before the 1990s. In that reporting, 1992 was around the time that clusters of reports began making the news:

1985 — In one of the first major abuse cases to become public, Louisiana priest Gilbert Gauthe pleads guilty to 11 counts of molesting boys. He serves 10 years in prison.

1992 — Massachusetts priest James Porter is charged with sexually abusing more than two dozen boys and girls. Porter, who pleads guilty and is sentenced to 18 to 20 years in prison, is the first case in what becomes a major scandal in the Boston diocese.

1992 – At a meeting in South Bend, Ind., the U.S Conference of Catholic Bishops acknowledges that some bishops have attempted to cover up abuse.

1996 — Milwaukee’s archbishop writes to Cardinal Ratzinger calling for canonical trials for two priests in his diocese who are accused of sexual abuse, including Murphy. He receives no response. Over the next two years, Wisconsin bishops will press for Murphy’s dismissal but receive no encouragement from the Vatican.

1997 — Maciel is charged with sexually abusing seminarians and boys in his care. Ratzinger orders the investigation closed.

1999 — A Massachusetts court brings child rape charges against former priest John Geoghan. Throughout his career, Geoghan had been repeatedly accused of sexually molesting boys but was transferred from parish to parish until 1998, when he was finally defrocked.

NPR used chronological order, whereas a 2017 CNN.com timeline described cases in reverse chronological order:

Ireland, 2009

A bombshell report commissioned by the Irish government concluded that the Archdiocese of Dublin and other Catholic Church authorities in Ireland covered up clerical child abuse.The Dublin Archdiocese Commission of Investigation’s 720-page report said that it has “no doubt that clerical child sexual abuse was covered up” from January 1975 to May 2004, the time covered by the report. The commission had been set up in 2006 to look into allegations of child sexual abuse made against clergy in the Irish capital.

The report named 11 priests who had pleaded guilty to or were convicted of sexual assaults on children. Of the other 35, it gave pseudonyms to 33 of them and redacted the names of two.

USA, 2004

Children accused more than 4,000 priests of sexual abuse between 1950 and 2002, according to a report compiled by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.USA, 2002

Former priest John Geoghan became a central figure in the clergy sexual abuse crisis in Boston, along with Cardinal Bernard Law who admitted receiving a letter in 1984 outlining allegations of child molestation against Geoghan. Law assigned Geoghan to another parish despite the allegations.From 1962 to 1995, Geoghan sexually abused approximately 130 people, mostly grammar school boys, according to victims. Church officials ordered him to get treatment or transferred him, but kept him on as a priest. The Boston Globe coverage on sexual abuse by clergy brought the issue to the forefront. The story was later adapted into the award-winning movie Spotlight.

Geoghan was found guilty of molesting a boy in a swimming pool and sentenced to prison in 2002. A year later, he died after an attack by another inmate at the state prison.

Law resigned as archbishop of Boston in 2002.

Austria, 1998

Cardinal Hans Hermann Groër of Vienna was forced to give up all his duties amid allegations he molested young boys. A statement by Groer asked for forgiveness but made no admission of guilt, reported the BBC.

In October 2021, the BBC published a similar retrospective. Its more generalized timeline held:

How did this all come to light?

Although some accusations date back to the 1950s, molestation by priests was first given significant media attention in the 1980s, in the US and Canada.In the 1990s the issue began to grow, with stories emerging in Argentina, Australia and elsewhere. In 1995, the Archbishop of Vienna, in Austria, stepped down amid sexual abuse allegations, rocking the Church there.

Also in that decade, revelations began of widespread historical abuse in Ireland. By the early 2000s, sexual abuse within the Church was a major global story.

In the U.S., determined reporting by the Boston Globe newspaper (as captured in the 2015 film Spotlight) exposed widespread abuse and how paedophile priests were moved around by Church leaders instead of being held accountable. It prompted people to come forward across the US and around the world.

A Church-commissioned report in 2004 said more than 4,000 US Roman Catholic priests had faced sexual abuse allegations in the last 50 years, in cases involving more than 10,000 children – mostly boys.

Clusters of abuse cases began appearing in the public consciousness in the early 1990s, persisting through the mid-to-late portion of that decade. O’Connor’s home country of Ireland was one of the most notable in the scandal, which amounted to a “major global [news] story” as of “the early 2000s.”

In the excerpted BBC article, the outlet said “mostly boys” were victimized. However, O’Connor’s Wikipedia entry included a rarely mentioned detail about her own abuse at the hands of the Catholic Church in Ireland. In that excerpt, Wikipedia editors explained that O’Connor was remanded to a facility at the age of 15, due to her “shoplifting and truancy.” It went on to suggest O’Connor “thrived there … in some ways,” but quoted her as describing “panic and terror and agony”:

In 1979, O’Connor left her mother and went to live with her father, who had married Viola Margaret Suiter (née Cook) in Alexandria, Virginia, United States, three years prior in 1976. At the age of 15, her shoplifting and truancy led to her being placed for 18 months in a Magdalene asylum called the Grianán Training Centre run by the Order of Our Lady of Charity. In some ways, she thrived there, especially in the development of her writing and music, but she also chafed under the imposed conformity. Unruly students there were sometimes sent to sleep in the adjoining nursing home, an experience of which she later commented, “I have never—and probably will never—experience such panic and terror and agony over anything.”

Wikipedia described the facility as a “Magdalene asylum called the Grianán Training Centre run by the Order of Our Lady of Charity.”

Sinéad O’Connor and ‘Magdalene Laundries’ in Ireland

“Magdalene asylums” or “Magdalene laundries” were, as with the church scandals, the subject of scrutiny followed by myriad reports in the 1990s and 2000s.

Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) is an organization created in 2003, as their “About” page explained:

Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) was established in 2003. The group had two main objectives, which were: i) to bring about an official apology from the Irish State, and ii) the establishment of a compensation scheme for all Magdalene survivors. JFM was a not-for-profit, totally volunteer-run survivor advocacy group, advocating on behalf of women who spent time in Magdalene Laundries. JFM exited the political arena in May 2013 having achieved its aims of a State Apology and the establishment of a commission led by Mr Justice Quirke to establish a State Redress Scheme. At this point Justice for Magdalenes Research (JFMR) was established. The members of JFMR have been assisting survivors in a personal capacity since before May 2013 and continue to do this work. Click here to learn about the JFM political campaign from 2009-2013.

Another page on the organization’s website explained the facilities in harrowing detail:

WHAT WERE THE MAGDALENE LAUNDRIES?

From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until 1996, at least 10,000 (see below) girls and women were imprisoned, forced to carry out unpaid labour and subjected to severe psychological and physical maltreatment in Ireland’s Magdalene Institutions. These were carceral, punitive institutions that ran, commercial and for-profit businesses primarily laundries and needlework. After 1922, the Magdalene Laundries were operated by four religious orders (The Sisters of Mercy, The Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, the Sisters of Charity, and the Good Shepherd Sisters) in ten different locations around Ireland (click here for a map). The last Magdalene Laundry ceased operating on 25th October, 1996. The women and girls who suffered in the Magdalene Laundries included those who were perceived to be ‘promiscuous’, unmarried mothers, the daughters of unmarried mothers, those who were considered a burden on their families or the State, those who had been sexually abused, or had grown up in the care of the Church and State. Confined for decades on end – and isolated from their families and society at large – many of these women became institutionalised over time and therefore became utterly dependent on the relevant convents and unfit to re-enter society unaided.

[…]

It is true that some women and girls were committed to the laundries by non-State actors, including their families, or church groups, such as the Legion of Mary. This happened for an array of reasons – they feared scandal related to unmarried motherhood and illegitimacy, sexual abuse, incest, domestic abuse, disability and mental illness. Although the State was not directly involved in incarcerating these women and girls, it failed to protect and defend their individual liberty and human rights, as they had a right to expect in a democratic State governed by the rule of law. Whatever the reasons why women and girls were sent to the Magdalene Laundries, the State had duties to all of the women and girls in the Laundries (a) to prevent them from being held against their will, (b) not to exploit or benefit from their forced labour or servitude and (c) to care for these women and girls in terms of their rights to a safe workplace, to social welfare and (in terms of school-age girls) an education.

Another section described what life was life for the thousands of Irish girls and women indefinitely imprisoned and forced to work without compensation:

WHAT WERE CONDITIONS LIKE IN THESE INSTITUTIONS?

Once inside the convents, girls and women were imprisoned behind locked doors, barred or unreachable windows and high walls (oftentimes with broken glass cemented at the apex). They were usually given no information as to when or whether they would be released. Upon entry, their names were often changed and they were given an identification number. Many women recall being instructed not to speak about their home-place or family. Their hair was cut and their clothes were taken away and replaced with a drab uniform. A rule of silence was imposed at almost all times in Magdalene Laundries and, in many women’s experiences, friendships were forbidden. Correspondence with the outside was often intercepted or forbidden. Visits by friends or family were not encouraged and were monitored by nuns when they did occur.

The girls and women were forced to work from morning until evening – washing, ironing or packing laundry, and sewing, embroidering or doing other manual labour. These Laundries were run on a commercial, for-profit basis, but the girls and women received no pay. No contributions (‘stamps’) were paid on their behalf to statutory pension schemes. The laundry they washed came not only from members of the public, local businesses and religious institutions, but also from numerous government Departments, the defence forces, public hospitals, public schools, prisons and other State entities such as the parliament,, the Chief State Solicitor’s Office, the Office of Public Works, the Land Commission, CIE and Áras an Uachtaráin (the President’s Residence)(to name but a few).

Punishments for refusal to work included deprivation of meals, solitary confinement, physical abuse, forced kneeling for long periods or humiliation rituals, including shaving of hair. Survivors speak of constantly being under surveillance, being verbally insulted, feeling cold, having a poor diet and enduring humiliating and inadequate hygiene conditions. None of the girls received an education, and survivors dwell on this fact as determining their ‘loss of opportunity’ in later life.

It was common for the girls and women to believe that they would die inside. Many did: comparison of electoral registers against grave records at the Donnybrook location shows that over half of the women on electoral registers between 1954 and 1964 died in that institution. If girls or women escaped – perhaps in the back of a laundry van, out an open door at delivery or collection time, or by scaling the wall – they were often captured and returned by the local Gardaí [police in Ireland]. The nuns punished escapees, in many cases, by transferring them to a different Magdalene Laundry. If and when a girl or women was released, it was invariably without warning, without money and with only the clothes she was wearing. Some girls and women were given jobs in other institutions run by nuns; many fled abroad as soon as they could.

The State never regulated the Magdalene Laundries, despite its use of the institutions both as places of detention and care, its commercial dealings with them, its knowledge of the detention of young girls of school-going age, and its awareness that the girls and women were working for no pay. The IDC noted that the commercial laundry premises were subject to the Factories Acts, and that Factories Inspectors visited the Laundries from 1957 onwards. According to the IDC’s report, however, the inspectors were concerned with machinery and factory premises only. They did not question the age of the girls or the conditions under which the girls and women were forced to work and lived.

A 2018 New York Times profile on the Magdalene laundries reiterated that many detained women were “confined to the laundries for life and were forced to work long hours in poor conditions with bad food, no pay and little or no medical or educational support,” and “told they should toil as penance for their sins.” History.com examined the facilities in 2019, first describing their survivors as “pregnant or promiscuous women.”

Further into the piece, a woman incarcerated for the crime of being raped was quoted:

[Survivor Mary] Smith was incarcerated in the Sundays Well laundry in Cork after being raped; nuns told her it was “in case she got pregnant.” Once there, she was forced to cut her hair and take on a new name. She was not allowed to talk and was assigned backbreaking work in the laundry, where nuns regularly beat her for minor infractions and forced her to sleep in the cold. Due to the trauma she suffered, Smith doesn’t remember exactly how long she spent in Sundays Well. “To me it felt like my lifetime,” she said.

A passing mention of an infamous mass grave for infants in Tuam also appeared:

Some pregnant women were transferred to homes for unwed mothers, where they bore and temporarily lived with their babies and worked in conditions similar to those of the laundries. Babies were usually taken from their mothers and handed over to other families. In one of the most notorious homes, the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, scores of babies died. In 2014, remains of at least 796 babies were found in a septic tank in the home’s yard; the facility is still being investigated to reconstruct the story of what happened there.

As it turned out, “mass graves” were how the system was finally challenged and ended in the 1990s — with a 1992 and 1993 real estate transaction, not an investigation:

… the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity decided to sell some of its land in 1992. They applied to have 133 bodies moved from unmarked graves on the property, but the remains of 155 people were found. When journalists learned that only 75 death certificates existed, startled community members cried out for more information. The nuns explained there had been an administrative error, cremated all of the remains, and reburied them in another mass grave.

The discovery turned the Magdalene laundries from an open secret to front-page news. Suddenly, women began to testify about their experiences at the institutions, and to pressure the Irish government to hold the Catholic Church accountable and to pursue cases with the United Nations for human rights violations. Soon, the UN urged the Vatican to look into the matter, stating that “girls [at the laundries] were deprived of their identity, of education and often of food and essential medicines and were imposed with an obligation of silence and prohibited from having any contact with the outside world.”

Even in retrospect, it was difficult to say for sure whether Sinéad O’Connor’s SNL protest moved the needle in exposing Magdalene laundries — but it was likewise difficult to say it didn’t, as the facilities disappeared in 1996. On July 27 2023, IrishCentral.com republished “Sinéad O’Connor’s torment as a victim of the Catholic Church’s Magdalene Laundries,” an updated 2013 article that reported:

Sinead O’Connor’s 2013 interview was published just 24 hours after the release of a damning report on the Catholic Churches’ “Magdelene Laundries”, which highlighted state collusion with the Nuns who ran them.

O’Connor described how she was just 14 years old when she was sent to the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity laundry, in Dublin, after she was labeled a “problem child.” This particular Magdalene Laundry only shut its doors in 1996.

Original material from the 2013 version of the piece connected O’Connor’s protest with her incarceration:

The rock star explained how her 18 months in High Park in the Drumcondra suburb of Dublin left her so angry at the injustice that it was part of the reason she caused worldwide controversy by tearing up a picture of the Pope on live television.

She added: “It wasn’t the only reason, but it was one of them.”

Did Sinéad O’Connor ‘Hold Up a Photo of a Refugee Child’ at Her 1992 Rehearsal?

A second reverse image search for only the top portion of the Reddit image returned one match, a series of images titled “Sinead O’Connor Pope Incident Image Gallery Saturday Night Live October 3, 1992.”

No text appeared on that page, and no source or context beyond the title were provided for the image gallery. A July 26 2023 Cracked.com article about O’Connor’s SNL appearance recapped the night of the protest from a then-current perspective:

On Saturday, October 3, 1992 O’Connor joined host Tim Robbins as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live. O’Connor had just released her third album, Am I Not Your Girl?, the month prior, and the Dublin-born songbird seemed set to continue her meteoric rise in the music world. Then, at the end of a somber, solo performance of Bob Marley’s song “War,” O’Connor held a photograph of then-Pope John Paul II up to the camera before tearing it to shreds, imploring the SNL audience to “fight the real enemy.” O’Connor’s intent was to draw attention to the sexual abuse of children within the Catholic Church, an issue which, at the time, was poorly publicized and rarely discussed.

O’Connor’s image and career would be tarnished, trashed and all-but-destroyed in the months following the protest. Not only would Lorne Michaels ban her from SNL, but, for the rest of Season 18, hosts and musical guests, including Joe Pesci and Madonna, would use their time on the show to take pot shots at O’Connor, with the former even bragging that, if he were in the studio at the time of the protest, he would have beaten O’Connor for the offense. Thirty years later, let’s make something clear – nothing that SNL has done since O’Connor’s final appearance has been remotely as meaningful as her protest.

A 2021 Insider.com piece about the backlash (“Sinead O’Connor reveals she was pelted with ‘a load of eggs’ outside 30 Rock after ripping up a photo of the pope on ‘SNL'”) quoted O’Connor’s memoirs:

The “Nothing Compares 2 U” singer said NBC permanently banned her from appearing on the network ever again. She said being blacklisted hurt “a lot less than rapes hurt those Irish children.”

[…]

Despite the polarized reactions to her behavior on “SNL” (some have applauded O’Connor for drawing attention to abuse in the Catholic Church nearly a decade before the pope addressed it in 2001), the musician stands by her actions.

“I’m not sorry I did it. It was brilliant,” she told The New York Times in May ahead of the “Rememberings'” release, adding, “But it was very traumatizing.”

“It was open season on treating me like a crazy b—-,” O’Connor said.

Broadly, O’Connor’s 1992 SNL performance was one of the most (if not the most) well documented aspect of her life and career. But a Google search for “Sinéad O’Connor SNL rehearsal ‘refugee child'” once again returned few results.

One was a February 2013 Today.com listicle about the Catholic Church in pop culture:

It’s perhaps the most famous time the papacy met entertainment. In 1992, singer Sinead O’Connor tore up a photo of Pope John Paul II while singing Bob Marley’s “Evil” on “Saturday Night Live.” O’Connor first changed a lyric about racism to be about child abuse, referencing the church’s abuse scandals. She tore the picture while singing the word “evil,” then threw the pieces of the photo at the camera and said, “Fight the real enemy.” The gesture came as a shock to the show — during dress rehearsal, O’Connor simply held up a photo of a refugee child. On the following week’s show, host Joe Pesci held up the taped-back-together photo and instead ripped up one of O’Connor.

Another mention was a 2020 DublinLive.ie article, “In 1992, Sinéad O’Connor forced us all to confront the horrors of child abuse — and paid the price”:

Nobody has known this was going to happen — in the dress rehearsal, O’Connor had held up a picture of a child — but when he saw the singer going off-script, NBC Vice-President of Late Night Rick Ludwin said he “jumped out of [his] chair”, adding “I just knew we were in trouble”.

That claim did appear in O’Connor’s Wikipedia entry, but no source or citation accompanied it. It also appeared in a draft of a proposed page devoted solely to the incident:

Saturday Night Live had no foreknowledge of O’Connor’s plan; during the dress rehearsal, she held up a photo of a refugee child. NBC Vice-president of Late Night Rick Ludwin recalled that when he saw O’Connor’s action, he “literally jumped out of [his] chair”. SNL writer Paula Pell recalled personnel in the control booth discussing the cameras cutting away. The audience was completely silent, with no booing or applause; executive producer Lorne Michaels recalled that “the air went out the studio”. He ordered that the applause sign not be used …

… Saturday Night Live had no foreknowledge of O’Connor’s plan; during the dress rehearsal, she held up a photo of a refugee child. NBC Vice-president of Late Night Rick Ludwin recalled that when he saw O’Connor’s action, he “literally jumped out of [his] chair”. SNL writer Paula Pell recalled personnel in the control booth discussing the cameras cutting away. The audience was completely silent, with no booing or applause; executive producer Lorne Michaels recalled that “the air went out the studio”. He ordered that the applause sign not be used.

Both excerpts cited an archived, scanned copy of an October 1992 article about the incident in a regional newspaper. In that early reporting, Saturday Night Live executives repeatedly emphasized their purported lack of “foreknowledge” — but an exculpatory mention of the purported rehearsal photograph swap was curiously absent:

A partly paywalled 2002 Salon.com article by CNN’s Jake Tapper (“Sinéad Was Right”) made no visible mention of the rehearsal, reading in part:

Oct. 12, 2002 | NEW YORK — Roughly 10 years before I meet with her, Sinéad O’Connor, the shorn, angry, alt-rock balladeer, committed what seemed like career suicide. On “Saturday Night Live” the night of October 3, 1992, O’Connor implored the audience to “fight the real enemy,” whereupon she tore up a photograph of His Holiness Pope John Paul II.

I’ve come to talk to O’Connor [in October 2002] to discuss what almost no one seems to remember: She tore up that picture of the Pope to protest pedophilia in the Catholic Church and the complicity of church hierarchy.

Not that O’Connor didn’t try to make that clear. By singing the Bob Marley song “War” — and changing the line “fight racial injustice” to “fight sexual abuse” — she thought she would be bringing the issue of child sexual abuse to the national consciousness. But however widespread they may have been back in Dublin, revelations that various Catholic dioceses were defending pedophile priests, and shuffling them from parish to parish, were eons away from the American consciousness.

So instead she set off a firestorm of anti-O’Connor protests. Stunned, SNL executives didn’t know how to react as the switchboard lit up. Thousands of irate calls poured in. In the NBC control room, the director, Dave Wilson, purposely did not press the “applause” button. Less than two weeks later, O’Connor — whose 1990 Grammy-nominated album “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got,” with the hit single “Nothing Compares 2 U,” was No. 1 in Billboard for eight weeks — was booed off the stage at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at Madison Square Garden.

With the exception of one unattributed photograph, we were unable to locate any footage or direct accounts confirming the claim O’Connor’s SNL rehearsal involved a different photograph “of a refugee child.” Saturday Night Live‘s immediate condemnation of the protest was such that the story was difficult to accept at face value.

Summary

After Sinéad O’Connor died in late July 2023, claims she “held up a photo of a refugee child” at her Saturday Night Live dress rehearsal circulated on social media. O’Connor was intensely castigated for the protest, banned from future performances, and mocked; her accusations were later proven to be completely correct. An image supporting the claim existed, but we were unable to find any credible citations for the claim about O’Connor’s SNL rehearsal.

- Sinéad O’Connor, acclaimed Dublin singer, dies aged 56

- SNL had no idea Sinéad O'Connor was going to rip up a picture of the Pope because she held up a photo of a refugee child during the 1992 rehearsal. | Reddit

- Sinead O'Connor SNL rehearsal | Google Trends

- "SINEAD O'CONNOR, the Irish singer, displayed a photograph of POPE JOHN PAUL II and tore it to bits during a live television appearance yesterday." | NYT Archive

- "Remember that photo of POPE JOHN PAUL II that the singer SINEAD O'CONNOR ripped up on "Saturday Night Live" | NYT Archive

- "More fallout from the furor caused by SINEAD O'CONNOR when she ripped up a photograph of the Pope ...

- "SINEAD O'CONNOR, the Irish rock singer who has come under attack for tearing up a picture of Pope JOHN PAUL II ..." | NYT Archive

- Why Sinead O'Connor Hit a Nerve | NYT Archive

- Sinead O'Connor open letter 1992 | Google Search

- Sinead O'Connor open letter 1992 | Los Angeles Times

- Timeline: Priest Abuse Claims Date Back Decades

- Timeline: A look at the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandals

- Catholic Church child sexual abuse scandal

- Sinéad O'Connor | Wikipedia

- Justice for Magdalenes (JFM)

- ABOUT THE MAGDALENE LAUNDRIES | JFM

- These Women Survived Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries. They’re Ready to Talk.

- How Ireland Turned ‘Fallen Women’ Into Slaves

- Magdalen plot had remains of 155 women

- Sinéad O’Connor's torment as a victim of the Catholic Church's Magdalene Laundries

- Sinead O'Connor Pope Incident Image Gallery Saturday Night Live October 3, 1992

- The Late Sinéad O'Connor's 'Saturday Night Live' Protest Is An Important Part Of The Show's Legacy

- Sinead O'Connor reveals she was pelted with 'a load of eggs' outside 30 Rock after ripping up a photo of the pope on 'SNL'

- Sinéad O'Connor SNL rehearsal 'refugee child' | Google Search

- Sinéad O'Connor SNL rehearsal 'refugee child' | Today.com

- In 1992, Sinéad O'Connor forced us all to confront the horrors of child abuse - and paid the price

- Draft:Sinéad O’Connor Saturday Night Live performance | Wikipedia