In late January and early February 2022, various quotes and memes circulated as the nation continued to talk about (and argue over) a Tennessee school district’s decision to ban the Holocaust graphic novel Maus:

Among them was a quote from author Stephen King concerning the general topic of banned books.

Fact Check

Claim: A Stephen King "banned books" quote meme is properly attributed.

Description: The quote from meme format says – ‘When books are run out of school classrooms and libraries, I’m never much disturbed. Not as a citizen, not as a writer, not even as a schoolteacher … which I used to be.’. This quote is circulated in late January and early February 2022 after Tennessee school district’s decision to ban the Holocaust graphic novel ‘Maus’. The discourse led to the creation and circulation of a meme with the quote attributed to Stephen King.

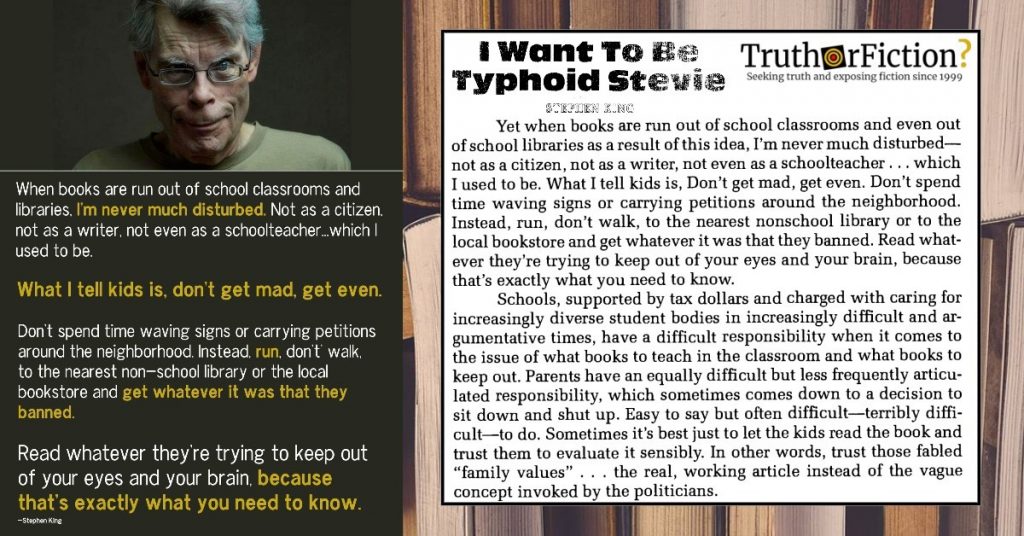

Primarily, the quote circulated in meme format. A version shared by the Facebook page “The Other 98%” on January 27 2022 had a six-figure share count, and a version shared to Twitter on the same date demonstrated strong engagement:

Underneath a photograph of King, text read:

When books are run out of school classrooms and libraries, I’m never much disturbed. Not as a citizen, not as a writer, not even as a schoolteacher … which I used to be.

What I tell kids is, don’t get mad, get even.

Don’t spend time waving signs or carrying petitions around the neighborhood. Instead, run, don’t walk, to the nearest non-school library or the local bookstore and get whatever it was that they banned.

Read whatever they’re trying to keep out of your eyes and your brain, because that’s exactly what you need to know. – Stephen King

In the midst of the extremely intense discourse, King’s purported words proved to be extremely popular. Google Trends data indicated searches for “Stephen King” in the seven-day period ending February 1 2022 correlated with searches linked to the topic. Of the top five related searches, three included “Stephen King banned books quote,” “Stephen King on banned books,” and “Stephen King banned books.”

We searched for “Stephen King” and “When books are run out of …,” and a scant 45 total results were returned. Restricting search results for anything published prior to February 1 2021 (one year prior to the meme’s popularity) narrowed the results significantly. Only ten results were returned, most misdated or originating with Tumblr users.

A Google highlight was at the top of the page, linking to an unsubstantiated version shared to Goodreads at some point before November 12 2015. As we have previously reported, Goodreads is often the earliest source for misquotes and fabricated quotes which later go viral.

No citation or source appeared on the Goodreads entry. That iteration of the quote was longer:

“Censorship and the suppression of reading materials are rarely about family values and almost always about controlabout [sic] who is snapping the whip, who is saying no, and who is saying go. Censorship’s bottom line is this: if the novel Christine offends me, I don’t want just to make sure it’s kept from my kid; I want to make sure it’s kept from your kid, as well, and all the kids. This bit of intellectual arrogance, undemocratic and as old as time, is best expressed this way: “If it’s bad for me and my family, it’s bad for everyone’s family.”

Yet when books are run out of school classrooms and even out of school libraries as a result of this idea, I’m never much disturbed not as a citizen, not as a writer, not even as a schoolteacher . . . which I used to be. What I tell kids is, Don’t get mad, get even. Don’t spend time waving signs or carrying petitions around the neighborhood. Instead, run, don’t walk, to the nearest nonschool library or to the local bookstore and get whatever it was that they banned. Read whatever they’re trying to keep out of your eyes and your brain, because that’s exactly what you need to know.”

Of the ten results returned in our search, one was a difficult-to-read (and apparently manually scanned) PDF document, entitled “Reading Stephen King” on the website for the Education Resources Information Center, or “ERIC.” A section titled “I Want to be Typhoid Stevie” included an even longer version of the quote:

Remember, each writer is a one-of-a kind creature, and sooner or later we all fall off the shelf and break, like the vase you liked so much and cried over because not all the King’s horses and all the King’s men could put that puppy back together again. To ask a Judy Blume or Stephen King or even an R. L. Stine or Clive Cussler to spend his or her thirty or forty years of creative life not only writing books but defending them is unfair, impractical, and, it seems to me, a little absurd.

Don’t get me wrong — I have little or no use for censorship. I’ve done public service announcements on TV defending the fundamental right to read, I’ve given money to defeat referenda aimed at restricting the free flow of information, and you’ll put a V-chip in my TV remote only when you pry it from my cold, dead fingers. I have a problem with people who want to take The Catcher in the Rye or Bastard Out of Carolina out of the high schools and keep the shotguns in Wal-Mart, just as I have a problem with legislators who, at the same time, want to outlaw abortions and federal assistance programs aimed at helping single mothers. The attitude seems to be that it’s wrong to vacuum ’em or drown ’em in saline, but perfectly okay to starve them once they’re out, named, and properly baptized. I have the same problem with politicians who inveigh heavily against drugs such as pot and heroin but continue to support business interests which spend millions of dollars to teach our kids what fun it is to freebase nicotine. I can’t think of these things too long. It makes me crazy. I Hulk out. And the Hulk doesn’t write.

People who want certain books out of schools or out of the libraries will tell you that they want to protect their children from certain ideas, certain words, and certain views of American life and the human condition. The fact that they are denying these things to all the other kids around their own . . . well, they’ll say, that’s just too bad; tough titty, said the kitty, but the milk’s not warm. Push them a little further and they’ll invoke “family values,” a phrase which more and more frequently makes me feel like collapsing in a fit of projectile vomiting.

Censorship and the suppression of reading materials are rarely about family values and almost always about control about who is snapping the whip, who is saying no, and who is saying go. Censorship’s bottom line is this: if the novel Christine offends me, I don’t want just to make sure it’s kept from my kid; I want to make sure it’s kept from your kid, as well, and all the kids. This bit of intellectual arrogance, undemocratic and as old as time, is best expressed this way: “If it’s bad for me and my family, it’s bad for everyone’s family.”

Yet when books are run out of school classrooms and even out of school libraries as a result of this idea, I’m never much disturbed not as a citizen, not as a writer, not even as a schoolteacher . . . which I used to be. What I tell kids is, Don’t get mad, get even. Don’t spend time waving signs or carrying petitions around the neighborhood. Instead, run, don’t walk, to the nearest nonschool library or to the local bookstore and get whatever it was that they banned. Read whatever they’re trying to keep out of your eyes and your brain, because that’s exactly what you need to know.

Schools, supported by tax dollars and charged with caring for increasingly diverse student bodies in increasingly difficult and argumentative times, have a difficult responsibility when it comes to the issue of what books to teach in the classroom and what books to keep out. Parents have an equally difficult but less frequently articulated responsibility, which sometimes comes down to a decision to sit down and shut up. Easy to say but often difficult — terribly difficult — to do. Sometimes it’s best just to let the kids read the book and trust them to evaluate it sensibly. In other words, trust those fabled “family values” . . . the real, working article instead of the vague concept invoked by the politicians.

A companion page for the document, “Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature,” described the totality of the document and its context. It appeared to attribute the “I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie” essay to King himself:

This collection of essays grew out of the “Reading Stephen King Conference” held at the University of Maine in 1996. Stephen King’s books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including “mass market” popular literature in middle and high school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King’s fiction is among the most popular of “pop” literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King’s work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) “Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event” (Brenda Miller Power); (2) “I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie” (Stephen King) … Appended are a joint manifesto by National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and International Reading Association (IRA) concerning intellectual freedom; an excerpt from a teacher’s guide to selected horror short stories of Stephen King; and the conference program …

Separately, King’s website hosted a reprinted 1992 editorial he authored, “The Book-Banners: Adventure in Censorship is Stranger Than Fiction.” It began:

“When I came into my office last Thursday afternoon [in 1992], my desk was covered with those little pink message slips that are the prime mode of communication around my place. Maine Public Broadcasting had called, also Channel 2, the Associated Press, and even the Boston Globe. It seems the book-banners had been at it again, this time in Florida. They had pulled two of my books, “The Dead Zone” and “The Tommyknockers,” from the middle-school library shelves and were considering making them limited-access items in the high school library. What that means is that you can take the book out if you bring a note from your mom or your dad saying it’s OK.

My news-media callers all wanted the same thing — a comment. Since this was not the first time one or more of my books had been banned in a public school (nor the 15th), I simply gathered the pink slips up, tossed them in the wastebasket, and went about my day’s work. The only thought that crossed my mind was one strongly tinged with gratitude: There are places in the world where the powers that be ban the author as well as the author’s works when the subject matter or mode of expression displeases said powers. Look at Salman Rushdie, now living under a death sentence, or Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who spent eight years in a prison camp for calling Josef Stalin “the boss” and had to run for the west to avoid another stay after he won the Nobel Prize for “The Gulag Archipelago.”

Further into the column, King addressed students and book-banning parents, in commentary which closely aligned with the content of the meme:

So, just for the record, here is what I’d say if I still took time out from doing my work to defend it.

First, to the kids: There are people in your home town who have taken certain books off the shelves of your school library. Do not argue with them; do not protest; do not organize or attend rallies to have the books put back on their shelves. Don’t waste your time or your energy. Instead, hustle down to your public library, where these frightened people’s reach must fall short in a democracy, or to your local bookstore, and get a copy of what has been banned. Read it carefully and discover what it is your elders don’t want you to know. In many cases you’ll finish the banned book in question wondering what all the fuss was about. In others, however, you will find vital information about the human condition. It doesn’t hurt to remember that John Steinbeck, J.D. Salinger, and even Mark Twain have been banned in this country’s public schools over the last 20 years.

Second, to the parents in these towns: There are people out there who are deciding what your kids can read, and they don’t care what you think because they are positive their ideas of what’s proper and what’s not are better, clearer than your own. Do you believe they are? Think carefully before you decide to accord the book-banners this right of cancellation, and remember that they don’t believe in democracy but rather in a kind of intellectual autocracy. If they are left to their own devices, a great deal of good literature may soon disappear from the shelves of school libraries simply because good books — books that make us think and feel — always generate controversy.

At the bottom, a short field (“Inspiration”) read:

Stephen’s response to requests for his opinion on the banning of two of his books.

Discourse about Maus in late January and early February 2022 led to the apparent creation and circulation of a meme with a quote attributed to well-known author Stephen King on banned books. That quote was not very prominent on the internet, but we found it in a 1996 collection of essays, “Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature.” One essay, “I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie,” was attributed to King. It contained a longer version of the quote on the meme.

- Stephen King banned books quote | The Other 98%/Facebook

- Stephen King banned books quote | Twitter

- Stephen King banned books quote | Google Trends

- Stephen King "When books are run out of ..." | Google Search

- Stephen King "When books are run out of ..." | Google Search

- Stephen King banned books quote | Goodreads

- Reading Stephen King [PDF]

- Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

- The Book-Banners: Adventure in Censorship is Stranger Than Fiction