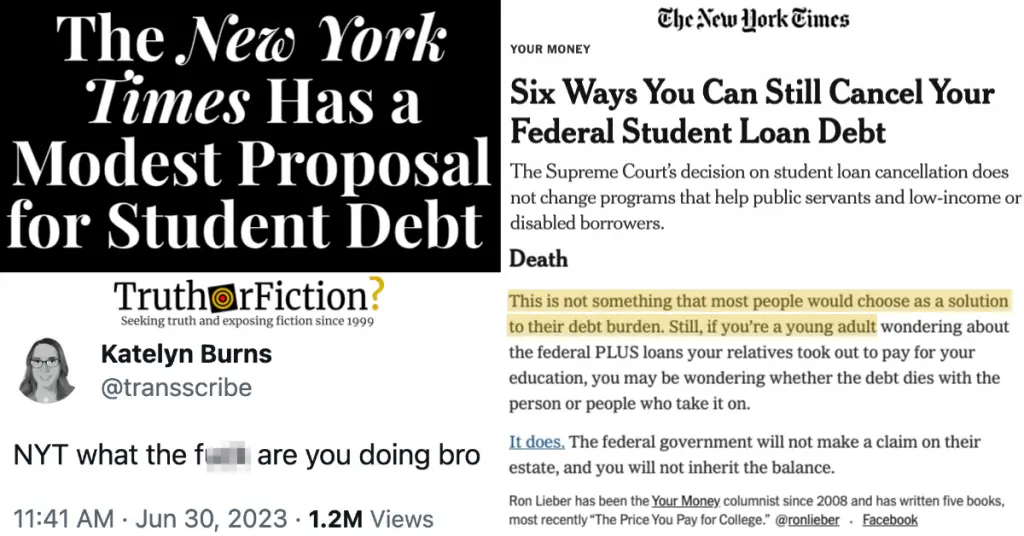

After the Supreme Court’s June 30 2023 ruling blocking the Biden administration’s student debt forgiveness program, screenshots of a New York Times article about “ways you can still cancel your student debt” were shared to Twitter by journalist Katelyn Burns:

The New York Times’ ‘Six Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt’

Burns attached two screenshots, neither of which was fully visible when embedded:

Fact Check

Claim: On June 30 2023, the New York Times published a list of “ways you can still cancel” student loan debt, including (and later eliding) a section titled “Death.”

Description: The New York Times published an article titled ‘Six Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt,’ which included a section labeled ‘Death.’ The article was later altered significantly, including changes to both content and title, without any acknowledgement indicating that an edit had been made.

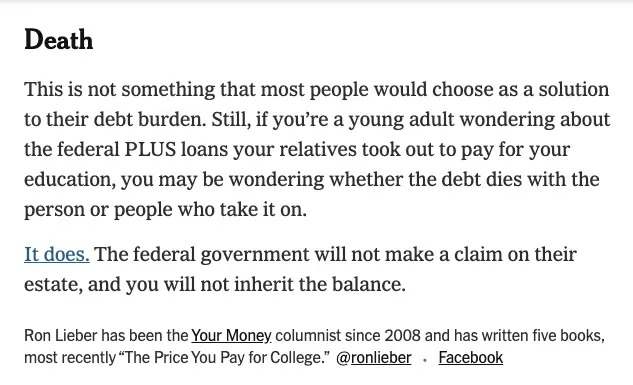

The first screenshot read in part:

Six Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt

The Supreme Court’s decision on student loan cancellation does not change programs that help public servants and low-income or disabled borrowers.

The second screenshot was more jarring; it appeared to represent one of the article’s “six ways you can still cancel” student loan debt. It said:

Death

This is not something that most people would choose as a solution to their debt burden. Still, if you’re a young adult wondering about the federal PLUS loans your relatives took out to pay for your education, you may be wondering whether the debt dies with the person or people who take it on.

It does. The federal government will not make a claim on their estate, and you will not inherit the balance.

Ron Lieber has been the Your Money columnist since 2008 and has written five books, most recently “The Price You Pay for College.” @ronlieber • Facebook

Burns did not offer a link to the story, but a version of the article was accessible on the New York Times‘ website, published on June 30 2023. Its headline differed from the one in the screenshot: “Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt.”

In it, the “Death” second was gone. Instead, the word “death” appeared only a single time, in a section labeled “Disability Discharge”:

Otherwise, according to the Education Department, a doctor would need to certify that you were “unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity due to a physical or mental impairment” that could be “expected” to result in death, had been continuous for at least five years or could be expected to last for at least five years.

In the screenshots attached to Burns’ tweet, the “Death” section appeared at the end of the Times article. When we accessed the live version of the article, the same section read:

Debt Won’t Carry On

If you’re a young adult wondering about the federal PLUS loans your relatives took out to pay for your education, you may be wondering whether the debt dies with the person or people who take it on.

It does. The federal government will not make a claim on their estate, and you will not inherit the balance.

Ron Lieber has been the Your Money columnist since 2008 and has written five books, most recently “The Price You Pay for College.” More about Ron Lieber

Much of the language matched the text in the screenshot, but the section was titled “Debt Won’t Carry On” instead of “Death.” A portion of the text in the screenshot was not present in the live version of the article; in the screenshot, it read:

Death

This is not something that most people would choose as a solution to their debt burden. Still, […]

Stealth Editing and Archived Versions

A live version of the “Six Ways …” article did not match the screenshots shared by Burns on Twitter — but we were unable to find any indicators that the article had been changed after publication in a meaningful (or even minor) fashion, such as a clarification or a correction.

Nevertheless, the article was archived several times, and the screenshot on Twitter matched an archived copy of the article. A version of the same New York Times article was archived on June 30 2023, preserving the originally published article before it was edited.

Wikipedia maintained a concise entry titled “Stealth edit,” defining the term in the context of journalism:

A stealth edit occurs when an online resource is changed without any record of the change being preserved. The term has a negative connotation, as it is a technique which allows authors to attempt to retroactively change what is written.

A common scenario would be a reporter posting a diatribe against something, followed by a blogger posting that the reporter is too extreme, followed by the reporter stealth editing the original post to be less extreme. The result is that the blogger looks like the one who is too extreme, since the public can’t tell that the original post has been changed.

The existence of stealth edits may often be detected by comparing the current contents of a web page against Google’s cache of the same page. In some cases, stealth editing of online content can be manually identified by making use of a web archiving service.

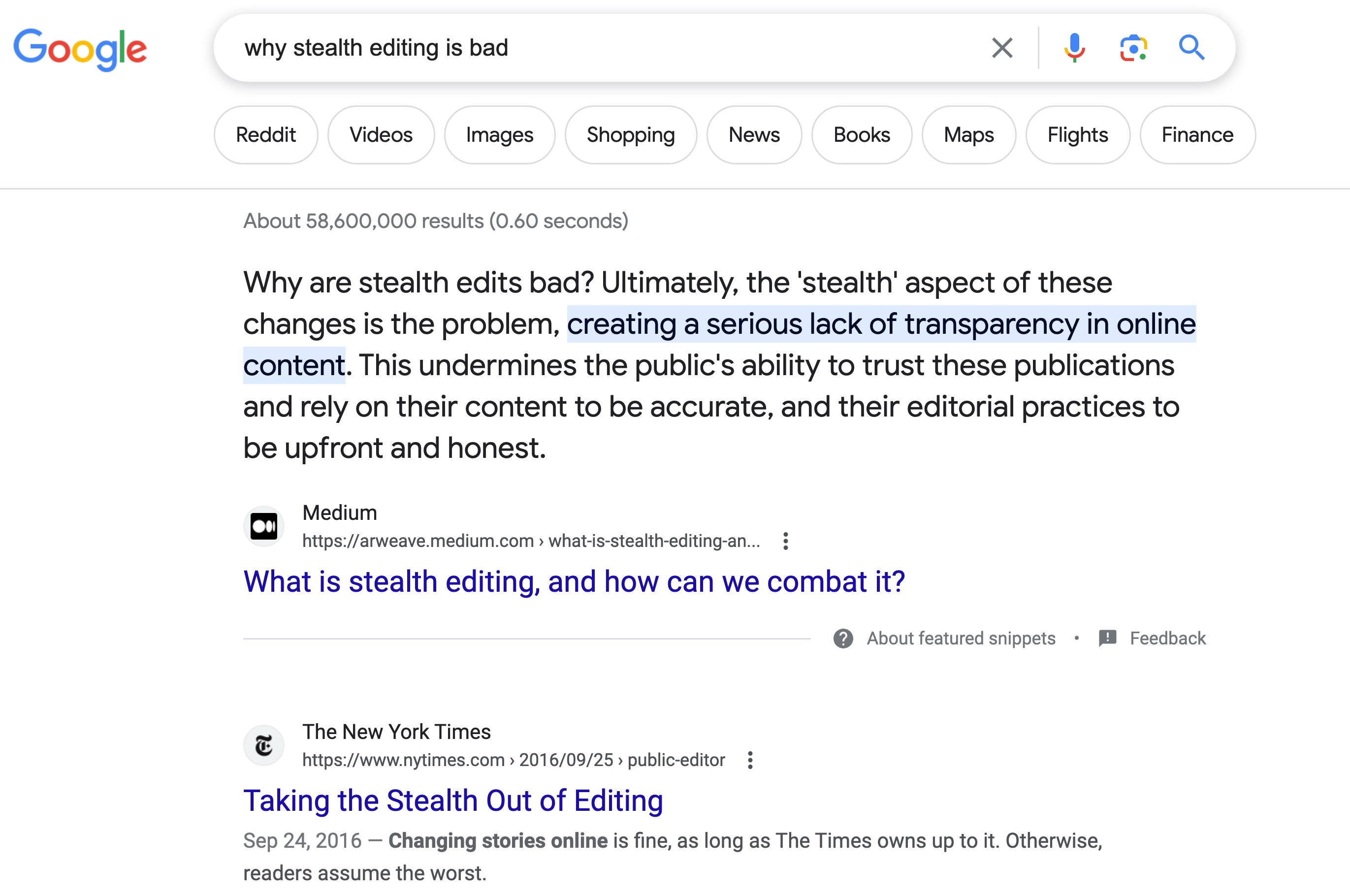

A Google search for “why stealth editing is bad” returned a New York Times article as the first matching result (beneath a Google snippet):

In September 2016, the New York Times published the article excerpted above, “Taking the Stealth Out of Editing.” The text in the Google preview did not appear in the article:

Sep 24, 2016 — Changing stories online is fine, as long as The Times owns up to it. Otherwise, readers assume the worst.

It was published in a since-discontinued column by then-current public editor Liz Spayd. Spayd opened the piece with an example of stealth editing by the New York Times in March 2013, articulating that it lacked any indicators that it had been edited:

In the history of do-overs at The New York Times, there is one example that may seem of no large consequence but nonetheless infuriated readers. It involved an obituary about a rocket scientist named Yvonne Brill. In its first incarnation, the obit referred to 88-year-old Brill in the first paragraph as a woman who “made a mean beef stroganoff, followed her husband around from job to job and took eight years off to raise three children.” In secondary fashion, it mentioned that Brill was a pioneering scientist who invented a propulsion system that kept communications satellites in orbit.

Seven hours later, after infuriated readers let loose, that version disappeared and a new story popped up with a less chauvinistic perspective emphasizing her exceptional career. No editor’s note or other explanation for the changes was given.

Spayd stated that the newspaper’s editors “have thus far rejected appeals to flag readers when stories are reworked, unless it’s a correction.” Spayd then articulated how “stealth edits” undermine reader trust in outlets and journalism in general:

“The vast majority of readers come to a story and get the best, most complete version we have. They read it and go away,” said Phil Corbett, who oversees standards and ethics in the newsroom. Billboarding changes, he says, would be unwieldy to carry out and of no interest to most readers.

I disagree on all points. This strikes me as an ossified policy in clear need of modernizing. Readers, I believe, are far more sophisticated than they’re given credit for and want more transparency in stories that are shapeshifting before their eyes. When changes affect a story’s overall tone or make earlier facts obsolete, or when added context recasts a story, readers should be told.

Putting a note on every update is unnecessary. But giving readers insight into why some stories were substantively changed conveys openness and reduces suspicion that editors are trying to get away with something.

Several more examples followed, including meaningful edits on 2016 election-related news involving Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and Bernie Sanders. In the cited examples, articles about current events underwent large (and unlabeled) edits after publication:

Then there was the post-publication editing that everyone at The Times wants to forget — a piece about Bernie Sanders that was so radically changed it went from fawning to fierce in a matter of hours.

One reader, Adam Smith-Kipnis, eloquently framed the issue in an email to this office. “The kerfuffle about ‘stealth editing’ highlights a transparency problem at the intersection of journalism, ethics and user experience design,” he wrote. “This problem is not faced only by the Times, but it’s one where the Times can take the lead by automatically including links to version history.”

Clicking “The Public Editor” at the top of the piece linked to a list of articles attributed to the New York Times’ public editor, presented in reverse chronological order. Spayd’s most recent contribution was published on June 2 2017, headlined “The Public Editor Signs Off,” and bearing the following subheading:

The New York Times may no longer have a public editor, but if that role’s extinguished, who will watch the watchdog?

In Spayd’s parting column, she expressed concern about a country “calcified into two partisan halves,” in conjunction with receding public trust:

And who will be watching, on this subject or anything else, if [large newsrooms] don’t acquit themselves well? At The Times, it won’t be the public editor. As announced on Wednesday [May 31 2017], that position is being eliminated, making this my last column. Media pundits and many readers [in May and June. 2017] were questioning the decision to end this role, fearing that without it, no one will have the authority, insider perspective or ability to demand answers from top Times editors. There’s truth in that. But it overlooks a larger issue.

It’s not really about how many critics there are, or where they’re positioned, or what Times editor can be rounded up to produce answers. It’s about having an institution that is willing to seriously listen to that criticism, willing to doubt its impulses and challenge the wisdom of the inner sanctum. Having the role was a sign of institutional integrity, and losing it sends an ambiguous signal: Is the leadership growing weary of such advice or simply searching for a new model? We’ll find out soon enough.

I leave this job plenty aware that I have opinions — especially about partisan journalism — that don’t always go over well with some of the media critics in New York and Washington. I’m not prone to worry much about stepping in line with conventional thinking. I try to hold an independent voice, to not cave to outside — or inside — pressure, and to say what I think, hopefully backed by an argument and at least a few facts. In this job, I started to know which columns would land like a grenade, and I’m glad to have stirred things up. I’ll wear it like a badge.

Summary

Following a June 30 2023 Supreme Court ruling on student debt forgiveness, the New York Times published “Six Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt,” featuring a section labeled “Death.” Under “Death,” the Times article originally indicated death was “not something that most people would choose as a solution to their debt burden. Still, if you’re a young adult …” Later on June 30 2023, the Times made major edits to the content and headline of the article, but failed to acknowledge that the piece had been altered.

- Supreme Court blocks Biden’s student loan forgiveness program

- NYT what the fuck are you doing bro | Twitter

- Six Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt | New York Times (live, stealth edited version)

- Six Ways You Can Still Cancel Your Federal Student Loan Debt | New York Times (archived version)

- Stealth edit | Wikipedia

- Why stealth editing is bad | Google Search

- Taking the Stealth Out of Editing | New York Times

- Yvonne Brill, a Pioneering Rocket Scientist, Dies at 88 | New York Times

- The Public Editor Signs Off | New York Times