The 5-second rule, a piece of folklore as much a part of our dining lexicon as "bon appétit," offers a curious intersection between science and superstition. This seemingly innocuous belief, that food dropped and quickly retrieved is safe to eat, bridges our understanding of microbiology with our reluctance to waste a perfectly good bite. But how does this rule hold up under the scrutiny of scientific investigation, and what does our adherence to it reveal about human nature? Let's sift through the evidence and societal implications to uncover the truth behind this enduring myth.

Understanding the 5-Second Rule

The 5-second rule is a widely recognized belief suggesting that if food dropped on the floor is picked up within five seconds, it's still safe to eat. Some sources trace the rule back to Genghis Khan, the Mongol ruler who supposedly enacted a much more generous version, allowing food to sit on the floor for hours without worry. Legend has it, this "Khan's rule" was a display of power, showcasing his might and the cleanliness of his floors. Fast forward to modern times, and we're down to a mere five seconds.

Culturally, the 5-second rule reflects our quirky human nature to bend the rules of hygiene for the sake of salvaging that delicious bite, showing just how much we hate to see good food go to waste. It's a testament to our ability to rationalize, or perhaps our hope that not all germs are quick on the draw. Whether at a bustling party or in the quiet corners of the kitchen, invoking the rule prompts nods of understanding, if not always agreement.

Various studies into the rule have given us a mixed bag of results—some say the type of food and flooring can make a significant difference in bacteria transfer, while others suggest time isn't as big a factor as we'd hope. It turns out, some microscopic party-crashers are quite fast on their feet. A study by Rutgers University found that bacteria can transfer to food in less than one second, particularly on tile and stainless steel surfaces.1

Still, despite evidence suggesting we might be better off not eating that floor-bound french fry, the rule persists. It stands as a cultural phenomenon, reflecting society's collective bargain with the microscopic world: "If we're quick enough, maybe we'll get away with it this time."

Scientific Investigations into the 5-Second Rule

Scientists have tackled the 5-second rule by setting up various real-world scenarios to scrutinize the belief's scientific standing. By meticulously dropping different types of food on assorted surface materials, from stainless steel to carpet, these trials bring light to our understanding of bacterial transfer rates. Key in these studies is the attention to detail in the selection of foods, ranging from moisture-rich watermelon to drier, harder substances like cookies, offering a broad spectrum for analysis.

One noteworthy methodology involved clocking the exact duration food items remained in contact with floors, varying timings from below one second to over 30 seconds, to see if and how the duration influenced bacterial hitchhiking from floor to snack. This method tapped into the crux of the 5-second premise by benchmarking the safety window—if any exists—for consuming dropped food.

Bacteria playing pivotal roles in these scrutinies included notorious culprits like Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, whose presence on food can spell trouble. By culturing samples after food-floor contact, researchers could concretely measure how much of these unwanted guests transferred within different time frames. Such rigorous contamination checks offer tangible proof either damning or supporting the infamous rule.

Surfaces under the microscope weren't spared scrutiny either. The experiments considered diverse environments where dropping food might occur, comparing how bacterial communities differ between, say, wooden panels and tiled flooring or how a carpet's fuzzy architecture might surprisingly act as a bacterial barrier, contra to hard, slick surfaces that seemingly invite more microbial passengers.

This deep dive into various setups mimics real-life fumbles, providing a rich database on how our home's architectural choices can stealthily influence our health when snacks go astray. As findings from these explorations weave into the public perception, they enrich our discourse on hygiene practices. Whether or not the studies collectively trash or treasure the 5-second rule, they undeniably feed our curiosity and drive an appetite for informed choices in our daily lives.

Factors Influencing Bacterial Transfer

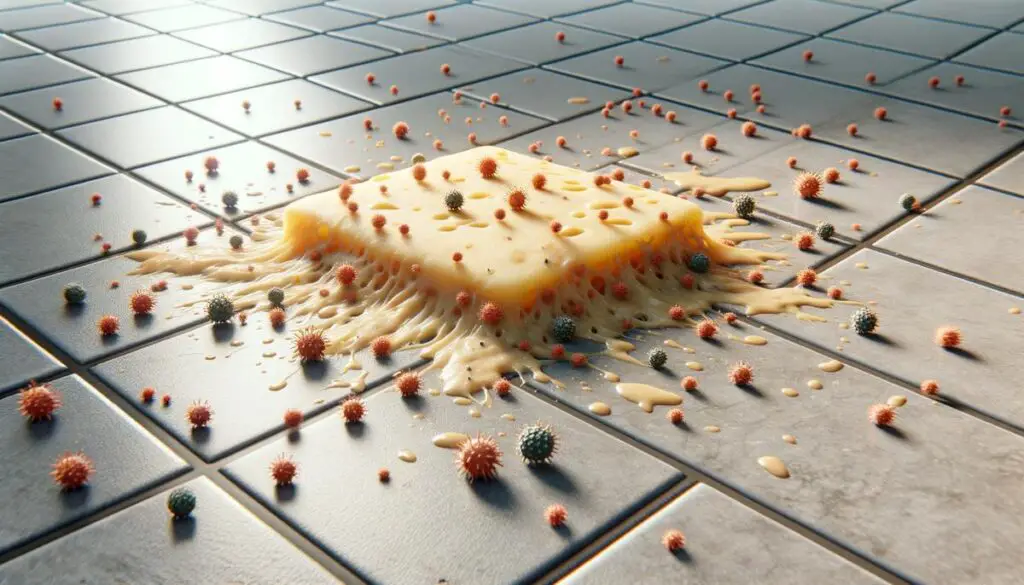

Flooring types play a massive role in how much bacteria hops onto your snack. Picture this: a juicy grape rolls off the table. If it lands on a plush carpet, less bacteria will likely make it a new home compared to if it smacks onto the kitchen tiles. Carpets, with their fibers, might seem like bacteria's best hideout, but they don't pass on as many germs to the food. That's because the carpet fibers decrease the actual surface area touching the food. On the flip side, hard surfaces like tiles give bacteria the red carpet treatment straight onto whatever dropped.

Now, let's talk about wet versus dry foods. If you drop something dry, like a cracker, the bacteria are less likely to hitch a ride on it. Think of the cracker as a desert – not much sticks in a dry environment. But let's say you drop a slice of watermelon. That's practically a pool party for bacteria. The moisture steers bacteria onto and into the food much quicker, making wet or moist foods more likely to grab a bunch of unwanted microscopic guests.

The seconds are ticking, but how many seconds until it's too late? You've heard the rule: "5 seconds, safe to eat; more than that, defeat." However, the grim reality is bacteria transfer can happen in less than those famous five seconds, especially on those non-carpeted, unforgiving surfaces. The length of time food dances with the floor does more than just decide its fate—it ramps up the bacterial count the longer it stays down there. A study published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology found that Salmonella Typhimurium can survive for up to four weeks on dry surfaces and can be transferred to food immediately upon contact.2

Given these tidbits of knowledge, the next time your favorite snack decides to take a tumble, you might weigh your next move a bit more carefully. Whether it's the heartbreak of saying goodbye to that last piece of pizza or the quick snatch and eat, remembering these key factors about moisture content, surface type, and contact time could make all the difference in the microscopic jungle we call home. So next time something drops, think fast, assess the scene, and maybe, just maybe, let that 5-second rule slide in favor of safety.

Health Risks Associated with the 5-Second Rule

When food gets cozy with the floor, it's like inviting microbes to a party. Think about the last time you dropped a slice of apple. Chances are, microscopic gate-crashers didn't wait for five seconds to hitch a ride. These unwanted guests can include more than just E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus, which were mentioned earlier. Here's a list of other potential party-crashers:

- Salmonella: Found mostly in raw poultry and eggs, it can make camp on countertops and floors, waiting for a free ride. Got an upset stomach, fever, or worse after eating that floor-touching pretzel? Salmonella could be the culprit.

- Listeria: Notorious for living it up in cooler temps, it's that uninvited guest that doesn't need much to thrive and is particularly fond of deli meats and soft cheeses.

- Norovirus: Often dubbed the stomach flu, this highly contagious virus needs but a brief encounter to spread. A chip falling on an area previously touched by an infected person can become a vehicle for this virus.

- Campylobacter: Mostly lurking around raw and undercooked poultry, it's got a talent for causing diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramps.

- Hepatitis A: Spread through microscopic bits of poop, it loves the low-key lifestyle on surfaces waiting for a lift. Reach for that floor-touched apple slice and you might just get more than you bargained for.

- Giardia: This parasite prefers the water to party in but won't say no to a quick mingle on your kitchen floor, especially around pet food bowls.

Bottom line: When your food hits the deck, think beyond the 5-second rule. These tiny intruders don't play by the rules and can gate-crash within milliseconds. Whether it's a tile or carpet, a piece of hard candy or a slice of bread hitting the floor spells bad news in terms of hygiene. It's always better to err on the side of caution than to invite these unseeable party-ruiners into your system. So next time, maybe let that piece of food go and spare yourself a possible trip down sick lane.

Public Perception vs. Scientific Reality

Despite the wealth of evidence challenging the validity of the 5-second rule, many continue to follow it based on tradition or convenience. This disconnect between scientific findings and public behavior reveals underlying factors that propel people to stick with the rule. One such factor is the overestimation of personal hygiene – individuals may assume their homes are cleaner than average, reducing perceived risks. Psychological comfort plays a role too; the minor rebellion of breaking a 'food safety' rule without immediate consequences can provide a sense of thrill. Social pressures also influence decisions. In a group setting, someone might apply the 5-second rule to avoid wasting food or to seem laid-back.

Risk assessment varies; people may consider the nutritional value of the dropped item and its scarcity before deciding. The allure of a delicious piece of food might outweigh hygiene concerns for some, underlining the clash between desire and rational health precautions. Humans show a remarkable willingness to engage in 'magical thinking,' where arbitrary rules are believed to provide control over uncontrollable situations. This cognitive bias assures some that a quick response can magically prevent contamination.

Disparities in education about food safety can lead people to underestimate risks. Misinformation or lack of awareness about how quickly bacteria can transfer to food often leads to misplaced confidence in the 5-second rule's effectiveness. People's faith in their immune systems also sways decisions; those who believe in their body's ability to fight off germs might see little harm in eating dropped food. These psychological and social constructs explain why the 5-second rule persists despite scientific debunking.

Curiosity about the truth of this rule doesn't necessarily lead to behavior change, evidencing the complex relationship between knowledge and action. Education on the subject often meets cognitive dissonance, where conflicting beliefs create discomfort, leading individuals to disregard new information that contradicts their prior habits. This psychological phenomenon solidifies adherence to the rule, as it's easier to dismiss scientific evidence than reevaluate personal beliefs and behaviors. A survey conducted by the Food and Brand Lab at Cornell University found that women were more likely to eat food dropped on the floor, with 55% of women versus 38% of men invoking the 5-second rule.3

Addressing this gap requires more than sharing facts; it calls for nuanced understandings of human behavior, aimed at reshaping norms around food safety from the ground up—literally. Providing practical, relatable alternatives to the rule, like quickly rinsing the dropped item, if appropriate, could bridge this divide, aligning public behavior with scientific advice for healthier eating practices.

In the grand scheme of things, the 5-second rule serves as more than just a decision-making tool for eating dropped food; it's a mirror reflecting our complex relationship with hygiene, risk, and waste. Despite the clear warnings from science, our collective willingness to gamble with microscopic dangers underscores a fascinating aspect of human behavior. Perhaps the most crucial takeaway is not whether we should eat food off the floor, but rather understanding why we're tempted to in the first place. This insight into our psyche may just be the key to fostering healthier, more informed decisions about what we choose to put in our mouths.

- Miranda, R. & Schaffner, D. (2016). Longer Contact Times Increase Cross-Contamination of Enterobacter aerogenes from Surfaces to Food. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 82 (21), 6490-6496.

- Dawson, P., Han, I., Cox, M., Black, C., & Simmons, L. (2007). Residence time and food contact time effects on transfer of Salmonella Typhimurium from tile, wood and carpet: testing the five-second rule. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 102(4), 945-953.

- Spizman, R. E. (2003). Survey: women more likely than men to eat food fallen on floor. Shape Magazine.