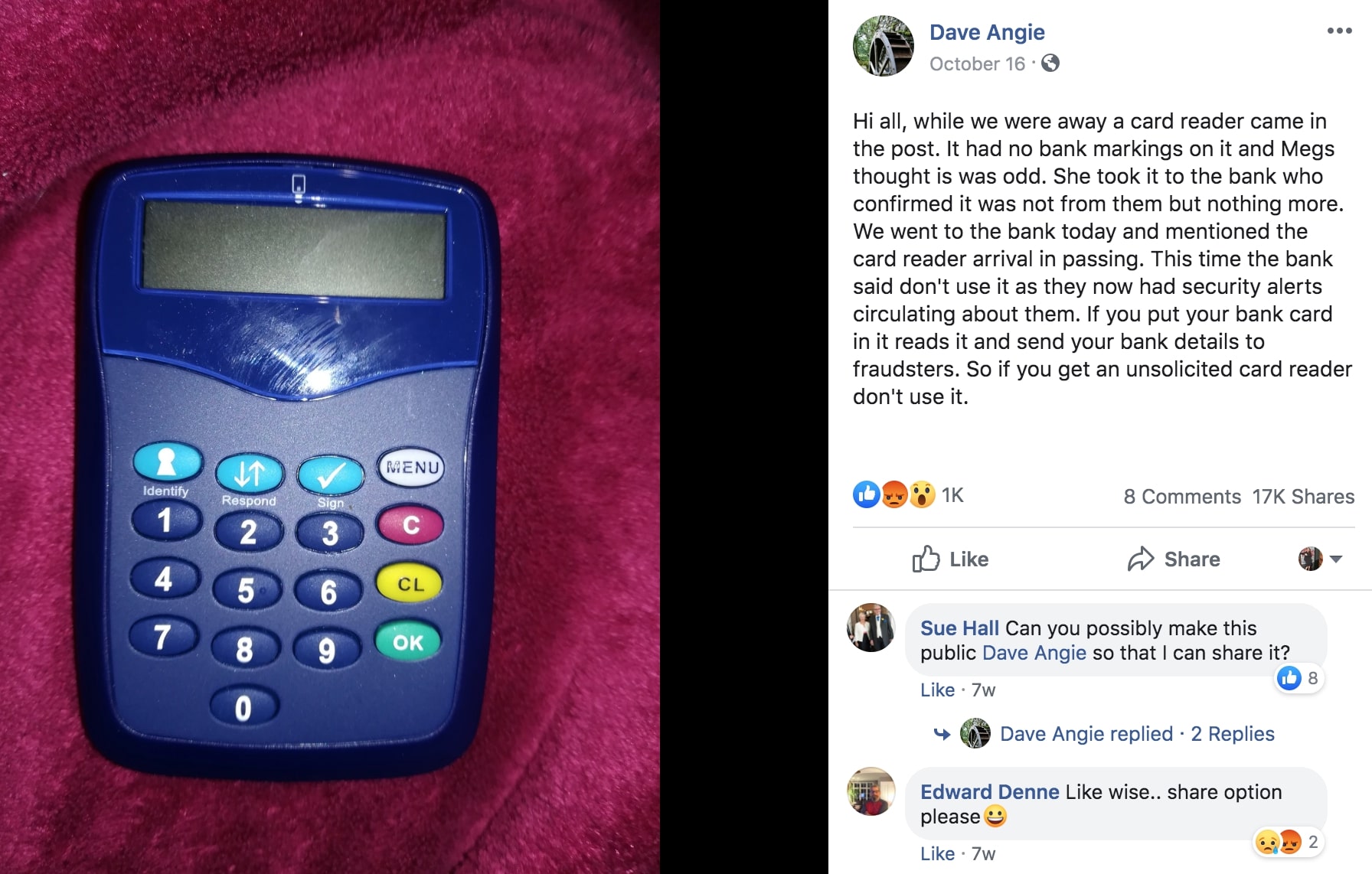

In October 2016, a Facebook user shared the following image of a purported “unsolicited card reader,” along with a nebulous warning to fellow users about the purported receipt of a an unexpected banking device in the mail:

An image shows what looks like a calculator against a purple fabric background. In the post, the user wrote:

Hi all, while we were away a card reader came in the post. It had no bank markings on it and Megs thought is was odd. She took it to the bank who confirmed it was not from them but nothing more. We went to the bank today and mentioned the card reader arrival in passing. This time the bank said don’t use it as they now had security alerts circulating about them. If you put your bank card in it reads it and send your bank details to fraudsters. So if you get an unsolicited card reader don’t use it.

In the warning, the user said “in the post” (phrasing which suggested that the poster was from outside United States), and their Facebook location was set in England. The user didn’t specify which bank they contacted, or from whom the unsolicited card reader was purportedly received.

The device shown in the photograph appears similar to one seen in an image published alongside a July 2017 Manchester Evening News article about an elderly woman falling victim to a sophisticated scam. According to that outlet, the scam hinged on her receipt of an unsolicited card reader in the mail (or post.)

However, that article appeared to source the totality of its information from an unverified Facebook post shared by an individual (rather than a bank or regulatory agency) in July 2017:

Although the article was more padded out than the Facebook post, it didn’t include any information from the bank (Royal Bank of Scotland) about unsolicited card readers specifically being sent or received by anyone. A spokesperson for that bank told the outlet indicated that devices like the one seen were used by Royal Bank of Scotland for authorization purposes.

That representative advised users not to supply third party reader codes to anyone over the phone, emphasizing that the bank will “never ask for” such codes. They also said that people who receive an unrequested card reader in the mail should report the device to the bank immediately:

A spokeswoman for The Royal Bank of Scotland, in response to the viral Facebook message, said the bank will never call and ask for card reader codes and if this happens, to end the call immediately.

She said: “The Royal Bank of Scotland uses a digital banking card reader to authorise transactions leaving your account via your digital banking. If you get a phone call saying it’s your bank, the police, or another company you trust and they ask for card reader codes, end the call immediately.

“Your bank will never ask for third party reader codes over the phone and you should not disclose these to any third party under any circumstances.

“If you receive a card reader in the post that you’ve not requested, report it to us immediately.”

In July 2017, Good Housekeeping UK also published an article about the Facebook post. It focused on “unsolicited card readers,” as well.

In April 2018, the Guardian reported that a recently widowed woman had fallen victim to what it called an “authorised push-payment scam.” Citing estimated total losses of £236 million in the United Kingdom in 2017 due to such scams, the outlet explained how a woman name Virginia Calder was victimized.

The Facebook posts both seemed to describe a specific issue: a compromised or unauthorized device. What the Guardian went on to describe was a completely different risk to consumers — phishing attacks:

The scammers usually start with a phone call purporting to be from the police or a bank, or with an email from a cloned address masquerading as a payment request from a genuine conveyancing solicitor or trader employed by the victim … In Calder’s case the timing was particularly cruel. She was widowed [in 2017] and left to juggle the care of three children with a full-time job as an academic. Also, last year, she had to take over the affairs of her mother who was diagnosed with dementia.

The fraudulent call came on the afternoon of her lumpectomy and it sounded plausible. “The caller ran through some initial security questions, such as the first line of my address and full name, then asked if I had made certain large purchases that day,” she says. “I confirmed I hadn’t because I’d been in hospital. He then told me my account had been frozen due to unusual transfers, and a large payment had been made. He promised to call back when I’d had time to log on to my account and check.”

The caller did ring back the next day, by which time Calder had established her account had, indeed, been marked “frozen” and that the £18,500 in her mother’s accounts had been transferred to her own.

When she asked the caller to verify his identity, he sent a text confirming his name and job title. “In my post-anaesthetic state, I thought it looked OK,” she says.

The fraudster explained that to protect her funds, the bank would set up a new account and she would be called to arrange for her balance to be transferred. “He told me to log into my account in the usual way, and set up a payment to V Calder for £20,000, using the sort code and account number given by him,” she says. “I did this, and used my card reader to authorise the transaction.” The next morning she called RBS to check all was OK. “I then realised they knew nothing about the transactions,” she says.

To be clear, nothing in Calder’s experience is necessarily suspicious at first glance. She received a call from what she believed was her bank, answered security questions, and received information her account had been “frozen.” After she confirmed her account was “marked ‘frozen,'” she asked the caller to verify their identity and received what she believed was a confirmation text — all immediately after she had undergone surgery, not long after losing her spouse.

According to the paper, scammers “elicit enough details to enter the victim’s account and make it look like there has been disreputable activity, by moving sums between accounts and renaming the account as ‘frozen.'” Calder logged in to confirm her “frozen” account after the thieves managed to log in and, presumably, change the name of the account to “frozen.”

After Calder received what she thought was a verification text, the purported bank employee advised her to use her bank-issued card reader as a means to unfreeze the funds she had in her account. Banking details were provided by the caller to Calder, and she used her “solicited” (expected and official) card reader to authorize the transaction.

According to that news story, the card reader played a role — not because it was sent or programmed by scammers, but because it was technically used in the manner it was intended to be used. Calder believed she was contacted by RBS, and like the elderly woman in the second Facebook post, she used her card reader to authorize a transfer of the money in her account to a second one:

To move funds out of her account, however, they would have needed authorisation via her card reader. RBS says it is not liable because she explicitly authorised the transfer. “The bank provides clear guidance on these scams,” it says. “Customers should never make a payment at the request of someone over the phone purporting to be from their bank. RBS would never ask a customer to move money to keep it safe from fraud.”

[…]

While customers who make payments by credit card are protected by law, those who make bank transfers have no legal right to a refund. Research by campaign group Which? found that 60% of respondents are unaware that transfers are unprotected.

The Guardian added, above, that in the United Kingdom, victims of “”authorised push-payment scams” were not protected by the same provisions entitling credit card customers to a refund of fraudulent transactions. The outlet said that new regulations in September 2018 might prevent some of that fraud from occurring, but Calder was forced to borrow money to replace the sum stolen in the fraudulent transaction.

The Royal Bank of Scotland is not the only bank to supply customers with card readers. A page on Barclays’ site tells customers not to be concerned if they unexpectedly receive a card reader in the mail, called “PINsentry”:

Why have I received a PINsentry card reader?

You’ve received this because your account has been upgraded to protect your transactions when you bank online. The PINsentry card reader is used to authenticate your identity by generating a one-off 8-digit code so that you can make use of all our Online Banking services.

Nothing on that page advises customers about push-payment scams or how to avoid being drawn into authorized push-payment scams. A separate Barclays page lists its PINsentry card reader as a protective measure against fraud. Notably, advice provided by banks to customers about card readers tends to be framed in terms of an additional layer of account security, with little immediate attention to vulnerabilities introduced by the devices (such as being misled to authorize fraudulent transactions):

Our PINsentry gives you a strong layer of protection to add to your log-in details, and helps keep your accounts even safer.

It works by asking you to insert your Barclays debit card and PIN into a card reader that we send you. The reader generates a unique security code that you’ll then need to type into Online Banking. And if you register for our app, you can get the code on your smartphone using Mobile PINsentry. That way, you get the extra security when logging in without needing to carry your card reader around.

Once again, no information about how to safely use the PINsentry card reader appears — but a first question about Barclays’ “Online and Mobile Banking guarantee” tacitly indicates that using it in the manner described by the victims would be unlikely to fall under that guarantee:

If a fraudster does manage to steal money from your account, you’re automatically protected by our Online and Mobile Banking Guarantee. This means we’ll refund your account straightaway — as long as you haven’t acted fraudulently or without reasonable care (for example, you haven’t kept your PIN written down with your card, or told someone else what it is).

Sections on Barclays’ “Fraud protection” page don’t automatically expand to show the individual answers to the questions on the page. In the second part of the fourth expandable menu, text explains:

What should I expect if someone does call?

If we do call, we’ll never ask for your passcodes, passwords, PIN, card details, PINsentry codes or sensitive account information. If we send you a text message, we’ll only ask you to reply with a ‘Y’ or an ‘N’. (These text messages are free to reply to in the UK and will cost no more than a standard text from other countries).

Although both Calder and the elderly woman scammed in authorized push-payment scams were customers of RBS, their page titled “What is a card-reader and how do I use one?” doesn’t mention the security measures necessary to avoid the scam in question. Customers who solely read that page would likely be more inclined to trust requests they use it, if they believed the request came from the bank:

A card reader gives you an extra level of security when using Digital Banking, and you may need to use it to confirm your identity when logging in if you don’t have a mobile number, or you’ve recently updated it with us.

A second page on the topic on the RBS site again encourages customers to trust the device while not emphasizing how to protect themselves when using it, going so far as to describe it as necessary:

A card reader is a security device needed by all customers when you’re banking digitally. It works with your Digital Banking service to provide an extra layer of protection against online fraud.

At the tail end of the page, RBS says:

We will never contact you to ask for your card reader details.

Going back to Calder’s experience, we quoted the Guardian‘s reporting above:

The fraudster explained that to protect her funds, the bank would set up a new account and she would be called to arrange for her balance to be transferred. “He told me to log into my account in the usual way, and set up a payment to V Calder for £20,000, using the sort code and account number given by him,” she says. “I did this, and used my card reader to authorise the transaction.”

It’s difficult to say for sure, but careful re-reading of Calder’s story suggested that no one had ever asked for her “card reader details.” By all accounts, Calder’s “mistake” was doing what she was advised by the actual bank and then scammers successfully posing as the bank to do — authorize transactions using her card reader. Moreover, Calder stated that “caller ran through some initial security questions, such as the first line of my address and full name,” suggesting she confirmed, but did not provide, that information to the scammer.

In all the card reader security pages from Barclays and RBS, customers are advised not to give out information about their card reader or their accounts or personal details over the phone. Calder did neither, and seemed to follow the Royal Bank of Scotland’s advice for using the device — to confirm transactions to the bank. All of that detail affirmed the title of the Guardian‘s reporting on the theft: “Uncovered: cruel scam so slick even the vigilant can be duped.”

Card-reader related warnings from banks in the United States tended to be issued in relation to public card-reading devices, like ATMs and retail pin pads. We were unable to locate any indication devices like Barclays’ PINSentry that were in widespread use in the United States, or that American banking customers were as susceptible to the authorized push-payment scam described in the reporting or the Facebook posts.

According to a Wikipedia page about the Chip Authentication Program (CAP), personal card readers were primarily in use in the United Kingdom and Sweden. That page cites 2009 research into the implementation and relative security value of handheld personal card readers [PDF], and in its abstract underscores a shift in the burden of fraudulent transactions from the banks to their customers:

We found numerous weaknesses that are due to design errors such as reusing authentication tokens, overloading data semantics, and failing to ensure freshness of responses. The overall strategic error was excessive optimisation. There are also policy implications. The move from signature to PIN for authorising point-of-sale transactions shifted liability from banks to customers; CAP introduces the same problem for online banking. It may also expose customers to physical harm.

That paper referenced an early attack in which scammers collected sufficient data to engage a successful phishing scam, and described ways that compromised public terminals could generate information to arm scammers with information about victims’ most recent bank card transactions (to claim the previous transaction was flagged.) Vulnerabilities described in the paper were of the sort to create a convincing impression of legitimacy when calls, texts, or emails are received by putative victims:

One example is an attack against the Novalis Ubuntu Institute in South Africa. Here, a phishing or malware attack collected the CFO’s account credentials. In themselves, these are not sufficient to place a transaction, because an authorisation code is also sent to the registered account holder’s mobile phone. So one criminal went to the mobile phone shop impersonating her driver, offered a counterfeit ID and the phone number of a female accomplice who impersonated the CFO herself, and requested a new SIM for the CFO’s account. He used this, along with the account credentials, to empty the institute’s account of R90 460 (approximately £6 000). We understand that the bank and phone company are disputing liability for this fraud.

A similar attack could be performed with CAP. The customer, using a tampered Chip & PIN terminal, would insert their card and enter their PIN as usual. The terminal would then generate the necessary CAP responses, and optionally also carry out the legitimate transaction. Shortly after, the customer would receive a personalised phone call or email, stating that a suspicious transaction had been noticed (stating the shop name they just used), asking for their online banking credentials. Since Barclays only uses identify and sign mode, there is no server-provided freshness or a timestamp, so the previously collected responses can be used, provided the customer had not logged into online banking in the meantime.

British banks commonly issue card readers to customers, and scammers have used the readers to breach security and empty accounts. Most official guidance on card readers issued by banks in the UK described them as enhanced security, not a source of increased vulnerability. We found no information outside of a 2017 Facebook post and reporting on it to suggest that unauthorized or unsolicited card readers were the primary problem when it came to card reader security.

A popular Facebook post warned users about receiving an “unsolicited card reader in the post,” and a 2017 version made similar claims. The older post prompted a number of news items about it, but the details were sufficiently fuzzy to be of little use. In the single detailed case of fraud we found, the victim was defrauded through her official, bank-issued card reader — not one received in the mail unexpectedly. In order to avoid the prevalent version of the scam, it was imperative for banking customers to understand that vulnerabilities were not necessarily posed by unknown card readers, but by convincing phishing attacks by entities or individuals skilled at posing as the bank itself. Victims of the scam appeared not only to have not provided information to scammers, merely confirmed it, but suffered losses when using their card readers in a manner seemingly consistent with bank guidelines.