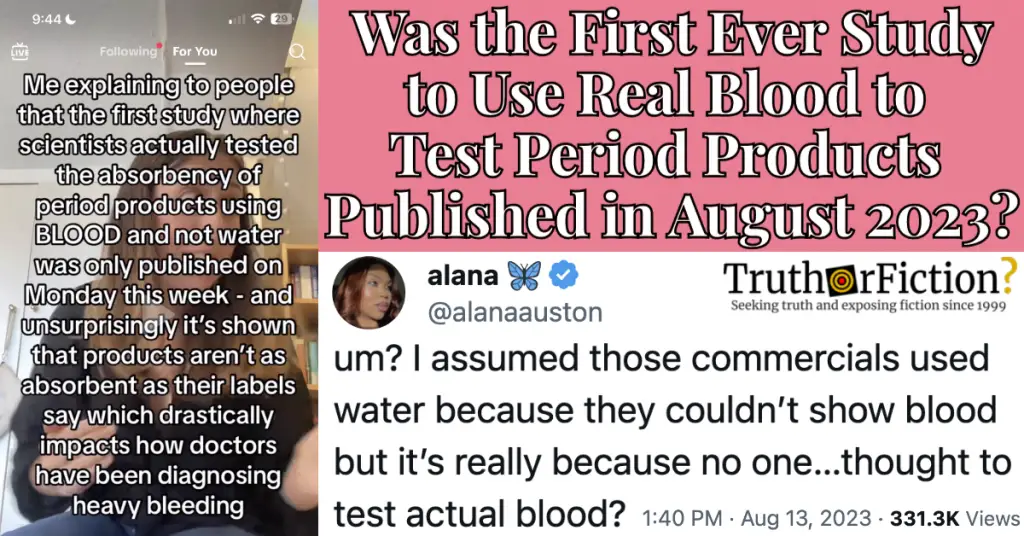

In August 2023, amid larger discussions and inauthentically organized narratives about reproductive health care such as abortion, a tweet about whether period products were “tested with real blood” swirled in the context of a claim around research about menstruation:

Period Product Testing Discourse on Social Media

On August 13 2023, Twitter user @alanaauston shared the tweet embedded above. The tweet also included an appended screenshot of an unnamed TikTok user included text.

Fact Check

Claim: The first study in which researchers used “real blood” to test period products was published in August 2023.

Description: In August 2023, a large debate arose around a study that examined the absorbency claims of period products by using real blood for the first time. The study revealed new insights into the capacity of these menstrual products, which has implications for understanding and diagnosing heavy menstrual bleeding.

Together, they read:

[@alanaauston] um? I assumed those commercials used water because they couldn’t show blood but it’s really because no one…thought to test actual blood?

[TikTok screenshot] Me explaining to people that the first study where scientists actually tested the absorbency of period products using BLOOD and not water was only published on Monday this week [August 7 2023] – and unsurprisingly it’s shown that products aren’t as absorbent as their labels say which drastically impacts how doctors have been diagnosing heavy bleeding[.]

In the tweet, @alanaauston discussed “commercials” for period products, and in the screenshot, the unidentified TikTok user made a few assertions: that the “first study where scientists actually tested the absorbency of period products using [blood]” was published in August 2023, that prior testing was deemed inaccurate by the published research, and that consequently, doctors were impeded in “diagnosing heavy bleeding.”

One commenter on the tweet tagged the purported TikTok creator behind the video:

On August 13 2023, TikTok user @unfabled.co published the clip seen in the screenshot. An appended status update read:

sorry but i’m here to tell you its taken until 2023 for scientists to study period product absorbency with blood and not just water #periodproblems #periodtok #womenshealth #genderhealthgap #womenshealthnews

Additional tweets reiterated the claim in August 2023:

Google Trends demonstrated an uptick in searches for “period products tested with blood” in the seven day period ending August 21 2023. Several Tumblr accounts shared versions of it in early and mid-August 2023.

On August 14 2023, the TikTok screenshot was shared to Reddit’s r/TrollXChromosomes, a popular companion subreddit to the subreddit r/TwoXChromosomes:

Comments on and replies to variations of these posts often made broad references to sex- and gender-based disparities in healthcare. An undated Northwell Health article, “Women have been overlooked in medical research for years,” explained:

Historically, women have gotten the short end of the stick when it comes to medical research.

For decades, male investigators published scientific articles based only on male subjects, whether they were animals or humans. A male investigator would ask a scientific question of interest to him and answer it with male data. When researchers were asked to justify those decisions in the 1940s and 1950s, they blamed it on—you guessed it— women’s hormones, claiming that females were more difficult to study because of menses and therefore should be left out of the research equation entirely.

One result of this lopsided research protocol: a belief that males are the standard and females are the aberration. As a result, women have been underdiagnosed, undertreated, and even given the wrong treatment regimens entirely for diseases as diverse as COPD, autoimmune disorders and heart disease.

On June 12 2023, an editorial on the topic (“Ending the neglect of women’s health in research”) was published in medical journal BMJ. It asserted in part that “dedicated funding and education for all researchers” were “urgently needed” to combat research gaps disproportionating affecting women and the care they receive.

Did a Study Confirm Period Products Weren’t ‘Tested with Real Blood’ in August 2023?

While several of the posts or comments on the referenced a specific study published on or around August 7 2023, details about that research rarely appeared.

In a threaded tweet, @alanaauston linked to an August 8 2023 article by The Guardian, “Menstrual discs may be better for heavy periods than pads or tampons – study.” Its headline didn’t align perfectly with the claim, but it began:

The first study to compare the absorption of period products using human blood suggests diaphragm-shaped menstrual discs may be better than traditional pads or tampons for dealing with heavy monthly blood flow.

The findings could also help doctors better assess whether heavy menstrual bleeding could be a sign of underlying health problems, such as a bleeding disorder or fibroids.

Manufacturers have traditionally used saline or water to estimate the absorption of their products, even though menstrual blood is more viscous and includes blood cells, secretions and tissue from the shed endometrial lining, all of which affect how it is absorbed.

Also, with the exception of tampons, there is no regulation on the labelling of period products, which makes it it difficult to assess whether one product is likely to be more absorbent than another.

The Guardian linked to an abstract for research published on August 7 2023 in the journal BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health: “Red blood cell capacity of modern menstrual products: considerations for assessing heavy menstrual bleeding.” The study itself existed behind a paywall, and the sum of the visible content read:

Abstract

Background Heavy menstrual bleeding affects up to one third of menstruating individuals and has a negative impact on quality of life. The diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding is based primarily on history taking, which is highly dependent on traditional disposable menstrual products such as pads and tampons. Only tampons undergo industry-regulated testing for absorption capacity. As use of alternative menstrual products is increasing, there is a need to understand how the capacity of these products compare to that of standard products.

Methods A variety of commercially available menstrual products (tampons, pads, menstrual cups and discs, and period underwear) were tested in the laboratory to determine their maximal capacity to absorb or fill using expired human packed red blood cells. The volume of blood necessary for saturation or filling of the product was recorded.

Results Of the 21 individual menstrual hygiene products tested, a menstrual disc (Ziggy, Jiangsu, China) held the most blood of any product (80 mL). The perineal ice-activated cold pack and period underwear held the least (<3 mL each). Of the product categories tested, on average, menstrual discs had the greatest capacity (61 mL) and period underwear held the least (2 mL). Tampons, pads (heavy/ultra), and menstrual cups held similar amounts of blood (approximately 20–50 mL).

Conclusion This study found considerable variability in red blood cell volume capacity of menstrual products. This emphasises the importance of asking individuals about the type of menstrual products they use and how they use them. Further understanding of capacity of newer menstrual products can help clinicians better quantify menstrual blood loss, identify individuals who may benefit from additional evaluation, and monitor treatment.

No part of the available abstract mentioned the use of saline for testing, nor did it indicate whether testing with blood or blood-like substances was uncommon. On August 7 2023, medical news outlet StatNews assessed the research and reported:

“These guys did something that I thought was very innovative and inventive,” said Paul Blumenthal, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University and one of the authors of the editorial accompanying the paper. He was not a part of this study. “I remember reflecting to myself when this paper came through … ‘Oh my goodness, after all this time, we don’t have good data on menstrual pads or menstrual products and their capacities?’”

[…]

Blumenthal added that the researcher’s use of red blood cells truly proves that “blood is thicker than water,” since they found different capacities than were advertised. In industry (and in commercials), companies usually use saline water to test the capacity of products.

The researchers used expired packed blood cells, the bagged kind found in blood banks, which are just red blood cells separated from whole blood. Neither form is really the same as menstrual blood, which also includes endometrial cells and vaginal secretions, but it is better than just using water or saline. And blood in its whole form is just harder to find. Doing this study using menstruating people would have also been very difficult since people bleed differently and their level of comfort might have affected results. According to Bannow, though, there is an ongoing study comparing the use of menstrual cups and period underwear in people with heavy menstrual bleeding.

An August 15 2023 Newsweek.com article (“Period Product Absorbency Test Uses Blood for the First Time”) included verbiage about the “first study” to use blood to test period products, purportedly quoting paywalled aspects of the study. It was not clear whether the claim originated with the research itself, or with the viral tweet embedded above:

Menstrual hygiene products like tampons and pads have now been compared by using blood during testing for the first time.

A study published in the journal BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health on August 7 [2023] is the first to compare the absorption of period products using human blood, finding that diaphragm-shaped menstrual discs may be better than pads or tampons at absorbing menstrual flow.

Manufacturers of period products have previously used saline or water to measure how absorbent they are. Menstrual blood, however, is much thicker than water, and contains endometrial tissue, mucus and other secretions, and is therefore absorbed at a different rate, according to the paper.

“No study exists comparing the capacity of currently available menstrual hygiene products using blood,” the study’s authors wrote. “Utilizing actual menstrual blood to test the collection capacity of menstrual hygiene products would be challenging, but blood products are a closer approximation than water or saline.”

A post explaining that this was the first study to use real blood to compare period products went viral on X, formerly Twitter.

Without access to the study itself, it was difficult to say for sure whether the claim was accurate. In the excerpted portion above, the study referenced “currently available menstrual hygiene products,” possibly describing the rising popularity of menstrual cups and disks.

A far less virally popular August 10 2023 article about the research (“Study assesses capacity of modern menstrual products to better diagnose heavy menstrual bleeding”) went into detail about the study. However, it did not mention the research being the “first” to use “real blood” to test menstrual products.

We contacted lead author of the study, Bethany Samuelson Bannow, M.D., assistant professor of medicine, division of hematology/medical oncology at the OHSU School of Medicine. Dr. Samuelson Bannow confirmed that the research was the first of its kind:

Our study was the first-ever analysis of the maximum absorbency of period products that was conducted with blood. Our original plan was to look into the capacity of sustainable products like menstrual cups, discs and period underwear, as these have not been incorporated into our diagnostic tools for heavy menstrual bleeding. We decided it would be best to look at the testing procedures for disposable products, and found nothing in the existing academic literature measuring the absorbency with blood; previous studies use the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s standard of gram of water or saline.

The standard of gram weight of saline was developed by the FDA in the 1980s for the Tampon Task Force, which was developed to standardize the absorption ratings of tampons to permit consumers to select the minimum absorption level for their needs, thus reducing risk of toxic shock syndrome. The goal was not about quantifying blood loss, but rather about standardizing options.

Note that blood is a precious resource that is difficult to obtain and requires precautions to work with that probably don’t fall within most period product companies’ standard operating procedures. Our study used expired units from our hospital’s blood bank. The blood bank has to stock all blood types and, while they do their best to minimize waste, some of the rare blood type products eventually expire. We simply asked the blood bank to provide expired units to us instead of disposing of them.

These factors have led to a gap in medical knowledge that we hope to ameliorate with this and other ongoing studies.

For us, the most important takeaway from our study is that people who require high-capacity period products need to be evaluated by their physicians for heavy bleeding.

Summary

A viral August 13 2023 tweet claimed that a study on the capacity of “period products” was the first of its kind to ever use “real blood” in testing. On August 7 2023, “Red blood cell capacity of modern menstrual products: considerations for assessing heavy menstrual bleeding” was published in the journal BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health. That research was largely paywalled, but its abstract asserted diagnoses of heavy bleeding were “highly dependent on traditional disposable menstrual products such as pads and tampons.” It further referenced “the capacity of currently available menstrual hygiene products,” which may have been a reference to the rising popularity of reusable products like cups, disks, and underwear.

The study’s lead author, Dr. Bethany Samuelson Bannow, responded to our statement, confirming that the study was the first of its kind to use blood to test the capacity of period products. The study can be read in its entirety here.

- um? I assumed those commercials used water because they couldn’t show blood but it’s really because no one…thought to test actual blood? | Twitter

- More than 12 million people have seen and are talking about our latest tiktok - and it’s no surprise. It’s taken until 2023 for scientists to study period product absorbency using actual blood? Let’s ???? do ???? better ???? | Twitter

- Testing period products with blood | TikTok

- Apparently the first ever study on period products using blood to test absorbency instead of water just came out this Monday. And guess what? Absolutely NONE of the period products on the market absorb anywhere CLOSE to what they say on the fucking packaging. | Twitter

- The year is 2023 & period products have now been tested w/ blood (instead of water or saline) for the 1st time EVER! Menstrual blood is thicker than water & contains other secretions. Menstrual discs better than pads or tampons at absorbing menstrual flow. | Twitter

- Testing period products with blood | Tumblr

- Testing period products with blood | Tumblr

- Testing period products with blood | Tumblr

- Women have been overlooked in medical research for years

- Ending the neglect of women’s health in research

- Testing period products with blood | Reddit

- Period products tested with blood | Google Trends

- Menstrual discs may be better for heavy periods than pads or tampons – study

- Red blood cell capacity of modern menstrual products: considerations for assessing heavy menstrual bleeding

- A new study put period products through the wringer. Discs came out a winner

- Period Product Absorbency Test Uses Blood for the First Time

- Study assesses capacity of modern menstrual products to better diagnose heavy menstrual bleeding