On May 2 2022, an Imgur user shared a screenshot of a tweet which claimed that on April 25 1886, the New York Times called the eight-hour workday movement “un-American,” and “blamed the ‘labor disturbances’ on ‘foreigners'”:

The post was titled “Look familiar?” It was shared to Imgur on May 2 2022, but the tweet was published on April 25 2022:

Fact Check

Claim: “Today in Labor History 4/25/1886: The New York Times called the eight-hour workday movement ‘un-American.’ and blamed the ‘labor disturbances’ on ‘foreigners.’ Other media predicted that the eight-hour day would cause loafing, gambling, rioting and drunkenness.'”

Description: The claim refers to a specific article published by The New York Times on April 25, 1886, which reportedly used the term ‘un-American’ to describe the eight-hour workday movement and blamed the ‘labor disturbances’ associated with the movement on ‘foreigners’. The term ‘labor disturbances’ could be interpreted as referring to strikes, protests, or other actions taken by workers in support of the movement.

Alongside the text of the tweet, a woodcut style triptych print was appended. Its three panels were all labeled “8 Hours,” and each third was labeled — “for work,” “for rest,” and “for what we will,” i.e. “free time.”

For additional context, the Library of Congress’s “Today in History” entry for “August 20” was titled “8-Hour Work Day,” and it began:

On August 20, 1866, the newly organized National Labor Union called on Congress to mandate an eight-hour workday. A coalition of skilled and unskilled workers, farmers, and reformers, the National Labor Union was created to pressure Congress to enact labor reforms. It dissolved in 1873 following a disappointing venture into third-party politics in the 1872 presidential election.

Efforts to introduce an eight hour workday had been ongoing for two decades as of 1886. That entry chronicled a lengthy labor effort to constrain work days to eight hours, explaining in its penultimate paragraph:

Progress toward an eight-hour day was minimal until June 1933 when Congress enacted the National Industrial Recovery Act, an emergency measure taken by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to the economic devastation of the Great Depression. The Act provided for the establishment of maximum hours, minimum wages, and the right to collective bargaining. Struck down by the Supreme Court in May 1935, the Recovery Act was soon replaced by the Wagner Act, which assured workers the right to unionize.

A very helpful “1886 in the United States” Wikipedia timeline shed a bit more light on the issues of April 1886. A bullet point for that period explained that just days later, events which eventually led to an eight-hour workday would unfold:

May 1 [1886] – A general strike begins in the United States, which escalates on May 4 [1886] into the Haymarket affair in Chicago and eventually wins the eight-hour workday in the U.S.

Tweet author Michael Dunn did not provide a direct link, but he did provide a specific newspaper (The New York Times), and a very specific date (April 25 1886). We searched for “unAmerican,” and one result was returned:

Clicking the link led to a page with the same headline (“Our Un-American Citizens.”) Under the headline, text indicated that the printed material was inaccessible to most readers:

The New York Times Archives

Full text is unavailable for this digitized archive article. Subscribers may view the full text of this article in its original form through TimesMachine.

A brief preview read:

It is a very common comment upon the labor troubles throughout the country that they are “un-American,” and it is as true as it is frequent …

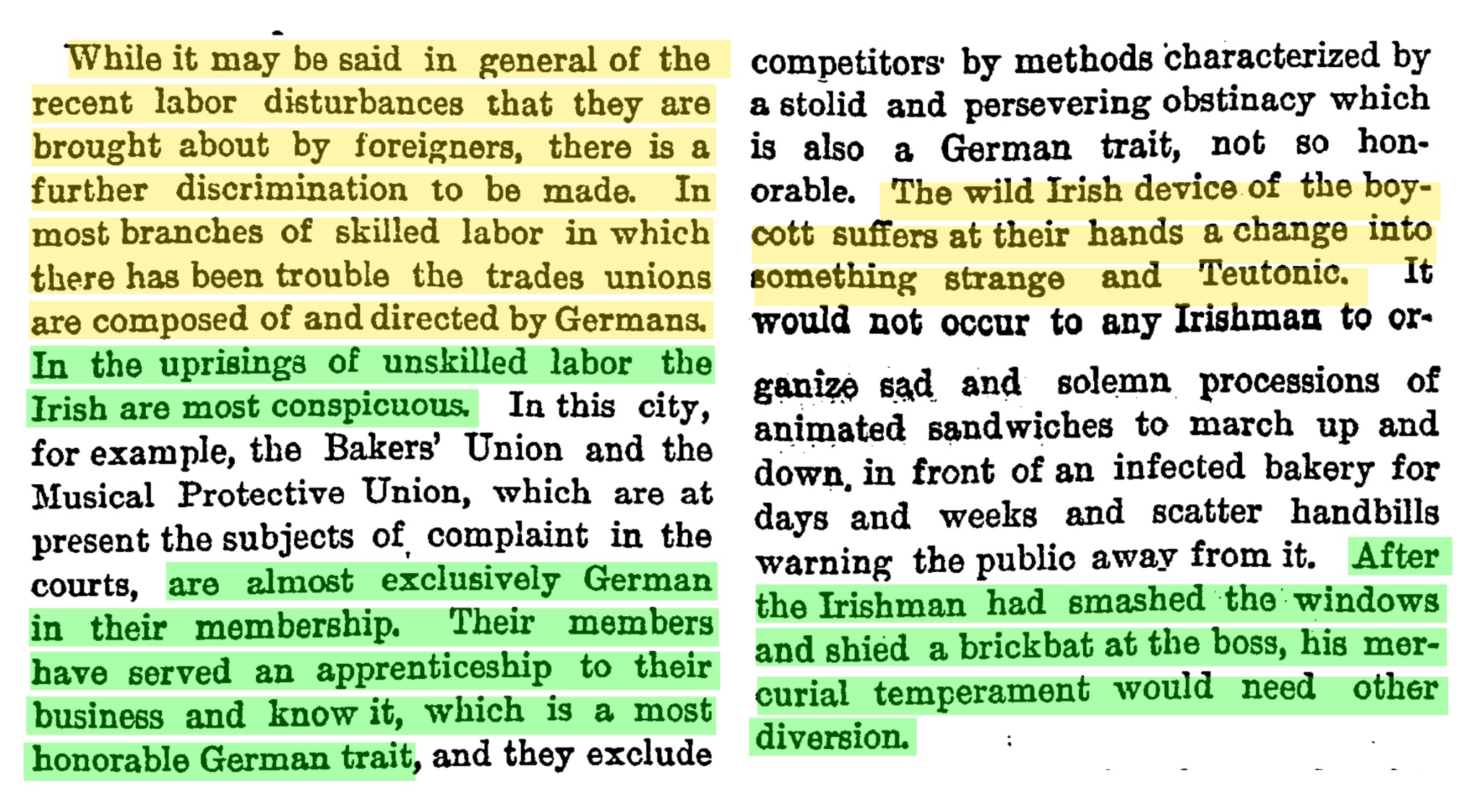

Text of the quoted material appeared on the eighth of the 16 pages that made up the April 25 1886 issue of the New York Times (paywalled). That excerpt appeared among a section that appeared to be possibly a form of “letters to the editor,” a larger excerpt contrasting purportedly quarrelsome Irish immigrant workers with their German counterparts:

Text in the above excerpt began:

While it may be said in general of the recent labor disturbances that they are brought about by foreigners, there is a further distinction to be made. In most branches of skilled labor in which there has been trouble the trades unions are composed of and directed by Germans. In the uprisings of unskilled labor the Irish are the most conspicuous …

Whoever authored “Our Un-American Citizens” provided examples of an “honorable German trait” alongside a “German trait … not so honorable,” adding:

The wild Irish device of the boycott suffers at their hands a change into something strange and Teutonic …

It concluded as follows:

Those final lines read:

It is of the utmost moment that this pretension should be once and for all put down, and that those who make it should be given to understand that any attempt to enforce it cannot be tolerated in a free country.

A popular April 25 2022 tweet shared to Imgur on May 2 2022 purportedly quoted April 25 1886 New York Times content in print, which described “the eight-hour workday movement [as] ‘un-American,'” and “blamed the ‘labor disturbances’ on ‘foreigners.'” The April 25 1886 edition of the New York Times was behind a paywall, but we were able to track down the material. The excerpt contrasted immigrants from different countries and their supposed tendencies, arguing that “any attempt to enforce it cannot be tolerated in a free country.” The missive was printed amid a tumultous time, just ahead of a whole series of planned national actions beginning on May 1 1886, and just days before the May 4 1886 “Haymarket affair.”

- New York Times April 25 1886 Labor Disturbances | Imgur

- New York Times April 25 1886 Labor Disturbances | Twitter

- 8-Hour Work Day | Library of Congress, Today in History, August 20

- 1886 in the United States | Wikipedia

- New York Times 'un-American' | Times Archive search

- OUR UN-AMERICAN CITIZENS. | New York Times, April 25 1886

- OUR UN-AMERICAN CITIZENS. | New York Times, April 25 1886