In the years since her death, Anne Frank has become a symbol of the effects of both fascism and political xenophobia. But a group named in her honor has debunked one of the more prolific online legends about her.

Born in Germany in February 1929, Frank came to prominence posthumously following the publication of her collected diary (a.k.a. The Diary of a Young Girl or The Diary of Anne Frank) in 1947, in which she detailed how she and her loved ones lived in exile in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam. She is believed to have died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in early 1945, less than a year after they were captured by the Gestapo.

While Frank’s Diary has gone on to be a staple of American public school curriculums, correspondence from her father Otto also made her story a parallel to the plight of refugees seeking entry into the United States. As the New York Times and other outlets reported in 2007, the New York City-based YIVO Institute for Jewish Research uncovered a file containing letters sent by Otto to contacts in the U.S. seeking their help in his efforts to bring the family to the United States for asylum.

According to the institute, Frank pointedly asked a college friend, Nathan Straus, Jr., for help:

In that letter, Otto Frank apologetically writes, “I would not ask if conditions here would not force me to do all I can in time to be able to avoid worse.” He goes on to stress that it was “for the sake of the children mainly that we have to care for. Our own fate is of less importance.” At the time of the letter, Jews in the Netherlands were facing increasing restrictions, having already been banned from owning radios and banned from the Civil Service, among other prohibitions; and an order had been issued requiring the registration of Jewish businesses. More directly urgent to Otto Frank was the fact that evidence (not included in the YIVO file) suggests he was being subjected to blackmail by a Dutch Nazi, and feared exposure and imprisonment as a racial and political opponent of the Nazi regime.

Strauss reportedly went to officials at the National Refugee Service, which at the time helped European nationals looking to escape the Nazis, for help to no avail. The Times reported:

Frank then tried to get to Cuba, a risky, expensive and often corrupt process. “The only way to get to a neutral country are visas or others States such as Cuba,” he said in a letter to Straus on Sept. 8. On Oct. 12, 1941, he wrote, “It is all much more difficult as one can imagine and is getting more complicated every day.”

Because of the uncertainty, Otto Frank decided to try for a single visa for himself. It was granted and forwarded to him on Dec. 1. No one knows if it arrived. Ten days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States and Havana canceled the visa.

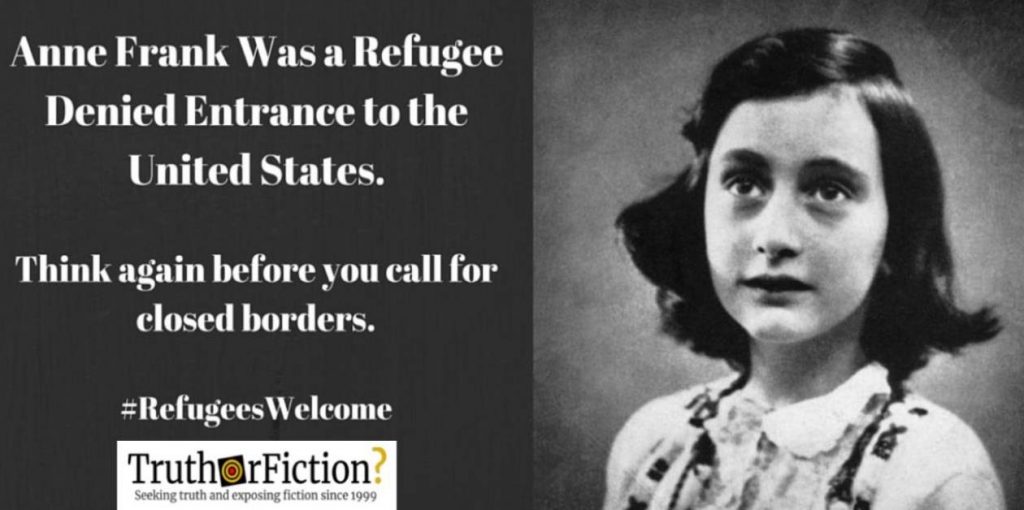

The discovery of her father’s correspondence drew parallels between Anne Frank and later populations seeking refugee status, particularly from Syria, which led to the creation of social media graphics and posts invoking her story on their behalf:

“Anne Frank could be a 77-year-old woman living in Boston today – a writer. That is what YIVO’s documents suggest,” American University professor Richard Breitman told NPR after Otto Frank’s letters were discovered. “The Frank family could have probably gotten out of the Netherlands even during much of the year 1941 but the decision to try hard came relatively late. The Nazis made it harder and harder over time and, by that time, the American government was making it harder and harder for foreigners to get in.”

But then in July 2018, the Amsterdam-based Anne Frank House museum, which was established in 1960 to preserve her legacy, published new research refuting the claim that the Franks were turned away by the U.S.

Working with the U.S. Holocaust Museum, the Anne Frank House found that after his Cuban visa was challenged, Otto Frank “joined the long queue” of Jewish residents of German descent who were “asked” to document their intention to leave the Netherlands regardless of their actual chances:

There are four registration slips, showing that all four family members — by now excluding Anne’s seriously ill maternal grandmother — were included in this process. Otto’s solicitor in their old hometown Frankfurt am Main wrote that he faced problems in procuring Edith’s birth certificate from Aachen, her hometown. This letter was dated November 11, 1941. That was by far too late to be of use in immigrating to the United States. Almost two weeks later Otto mentioned in a letter to his brother-in-law, Julius Holländer in Boston, that the whole family was vaccinated against typhus. Proof of this prophylaxis was mandatory for most countries. This letter, in retrospect, is even more devastating, as both Anne and Margot died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen in February 1945.

“Although the United States had a far from generous policy with regard to Jewish refugees, it is clear that Otto, Edith, Margot and Anne Frank were not refused entry to the United States,” the museum said in a statement on its website. “Because of all the developments, Otto’s immigration visa application to the American consulate in Rotterdam was never processed.”

Update 12/15/2022, 10:47am: This article has been revamped and updated. You can review the original here. — ag