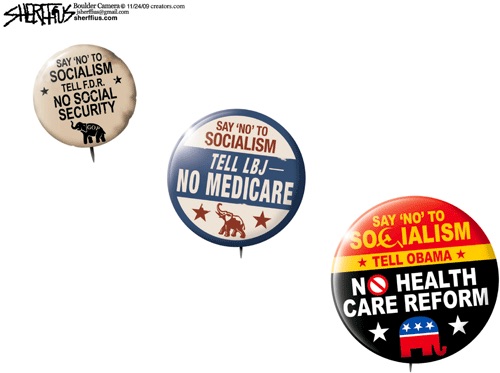

On February 21 2019, economist and former United States Secretary of Labor Robert Reich published a tweet alongside what appeared to be an image of two political buttons from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s and Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaigns:

Although Reich made no specific reference to the “say ‘no’ to socialism” buttons shown, he wrote:

For over 80 years, Republicans have used the term “socialist” to attack every Democratic program that’s become essential to the wellbeing of Americans.

The image featured two buttons or pins, both with an elephant, suggesting a Republican position:

SAY ‘NO’ TO SOCIALISM TELL F.D.R. NO SOCIAL SECURITY

SAY ‘NO’ TO SOCIALISM TELL LBJ NO MEDICARE

On first glance, it was a bit odd that two pins from very different eras (Roosevelt was president from 1933 through 1945, Johnson 1963 through 1969) would feature the same basic layout — the GOP elephant and the use of an identical phrase with the president and policy swapped out. Roosevelt was succeeded by Harry S. Truman and then Dwight Eisenhower, the latter a Republican who supported and expanded Roosevelt’s referenced New Deal.

According to the Roosevelt Institute, bipartisanship was a large factor in the adoption of programs like Social Security and the New Deal:

Many Americans, for example, assume that Franklin Roosevelt was able to get through such landmark pieces of legislation as the Social Security Act or the National Labor Relations Act because the Democrats held huge majorities in both houses of Congress. But the truth is that many of FDR’s harshest critics came from the conservative wing of the Democratic Party, while some of his strongest supporters were progressive Republicans.

In the early days of the New Deal, for example, FDR teamed up with Republican Senator George Norris of Nebraska to create the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), our nation’s first major regional supplier of public power. On May 8, 1933, also a part of the famous 100 days, Republican senators Robert La Follette Jr. of Wisconsin and Bronson Cutting of New Mexico joined forces with Edward Costigan of Colorado to sponsor a bill authorizing $6 billion in public works expenditures. Moreover, the director of one of the most important New Deal stimulus agencies, the Public Works Administration (PWA), which among other things built the Triborough Bridge and Lincoln Tunnel in New York, the Washington National Airport, the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, the Grand Coulee Dam, and thousands of miles of public highways, was led by the progressive Republican head of the Department of the Inferior, Harold Ickes.

Progressive Republicans even supported legislation aimed at securing the rights of workers to join unions and secure better wages, hours, and working conditions — the National Labor Relations Act and Fair Labor Standards Act — and the vast majority of Republicans in both the House and the Senate voted for the Social Security Act and the establishment of the Social Security Administration, whose first head was the former governor of the state of New Hampshire, Republican John G. Winant.

When it came down to votes in 1965, Republicans were nearly evenly split in the House and Senate. It is accurate to say that opposition to Medicare’s adoption under Johnson was intertwined with rhetoric about “socialism,” but the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library described the issue as less about partisanship than special interests:

In each case, the American Medical Association (AMA) was the chief culprit in killing the legislation, spending millions to brand the concept as “socialized medicine,” an ambiguous characterization that nonetheless made it intrinsically un-American. Conservatives also cast a wary eye. Actor Ronald Reagan, a darling of the growing conservative movement and soon-to-be California gubernatorial candidate, warned that such a program would “invade every area of freedom in this country” and would, in years to come, have Americans waxing wistful to future generations about “what it was like in America when men were free.”

But sixteen years after Truman’s efforts were derailed by an unwilling Congress, Johnson believed “the times had caught up with the idea.” On July 30, 1965, Johnson traveled to the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri, where the eighty-one-year-old Truman, lean and bent with age, his wife, Bess, in tow, watched Johnson sign Medicare into law.

Use of an elephant as a GOP symbol dates back to the 19th century. It is also true that archival campaign pins expressing disapproval for Roosevelt existed, and the style of button in the tweet was not entirely implausible:

The image as shared by Reich appeared in a 2016 blog post, but the author of the post noted that they were unable to vouch for the historical authenticity of the pins. A reverse image search revealed that versions of the image had been in circulation since roughly 2009, around the time the Affordable Care Act — also known as Obamacare — became a topic of debate.

Although the earliest appearances of the image crawled by the site were on forums and in blog posts, those iterations featured a larger and less degraded version of the image — with an additional button:

That version provided additional contextual clues. Its third button used the same format, and read:

SAY ‘NO’ TO SOCIALISM

TELL OBAMA NO HEALTH CARE REFORM

In that context, a signature and detail at the top right of the image revealed that the series of “buttons” were the apparent work of political cartoonist John Sherffius for the Boulder Daily Camera. Originally published on November 24 2009, the cartoon in its entirety was available in a November 30 2009 post titled “The History of Just Say No.”

As of February 2019, a modified version of the original work circulated on social media both in comments and in a high-profile tweet from Robert Reich. Reich made no mention of the origin of the image, leading some readers to believe that the buttons were authentic archival campaign material. However, their source was a 2009 political cartoon, and the commentary more apparent when the image was viewed in its original form.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Bipartisanship Made the New Deal Possible

- Medicare and Medicaid

- Vote Tallies for Passage of Medicare in 1965

- From the Museum

- Election 101:How did the Republican and Democratic parties get their animal symbols?

- Socialism Past, Present, and Future

- Wednesday Cartoon Fun: We're Screwed Edition

- The History of Just Say No

- About