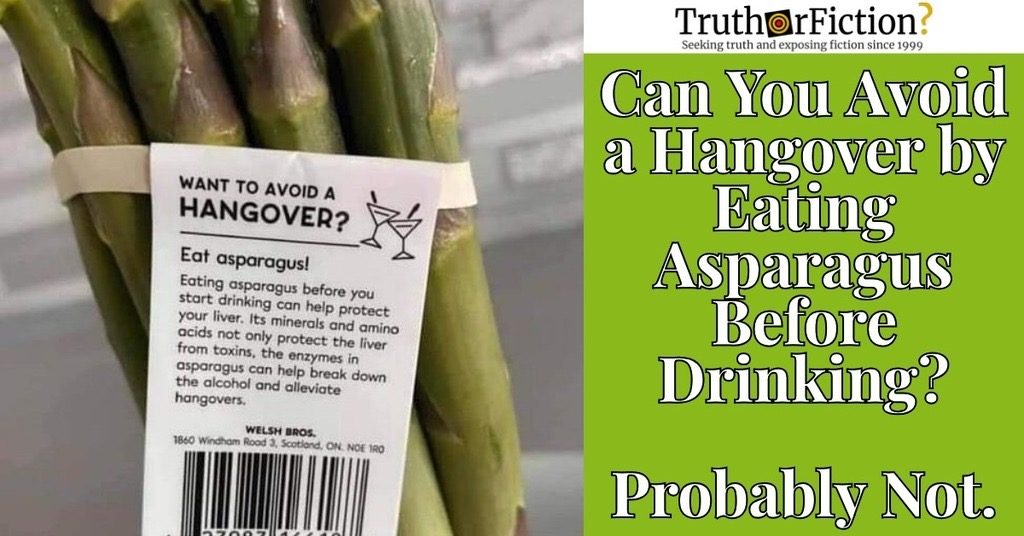

On May 24 2021, an Imgur image showed a bunch of asparagus promoting itself as a hangover cure if eaten before drinking alcohol, in a post titled “Time to party”:

‘Want to Avoid a Hangover? Eat Asparagus!’ Imgur Post

A close-up image of asparagus showed a bunch with its stalks secured with a rubber band and a tag bearing a Candian address saying:

WANT TO AVOID A HANGOVER?

Eat asparagus!

Eating asparagus before you start drinking can help protect your liver from toxins, the enzymes in asparagus can help break down the alcohol and alleviate hangovers.

WELSH BROS. 1860 Windham Road 3, Scotland, ON, [postcode]

As was expected, the tag did not contain any scientific citations, but Welsh Bros. is a real produce supplier in Ontario. A reverse image search returned just one result (the May 24 2021 Imgur post), suggesting that the original poster may have captured the image themselves and shared it to Imgur; a search for the wording on the tag also pointed back to the same Imgur post.

Welsh Bros.’ website stated that their asparagus was in season from early May to late June each year, further suggesting the image, if it was real, showed a new initiative and had been recently captured as of May 2021.

Hangover Cures in Human History

Canadian produce suppliers were far from the first people to examine or promote hangover cures, and asparagus was comparatively straightforward in terms of hangover history.

Food news site Eater.com delved into the history of hangover cures on December 31 2015, explaining first that scientific research on hangovers is self-limiting:

Since at least 10,000 BC, humans have been purposefully mixing fermented beverages and imbibing them. The Greek cult of Dionysus, for example, worshipped their wine-creating god by drinking too much. Meanwhile, the rest of Greek and Roman civilizations weren’t exactly teetotalers, either. There’s not much scholarship tracing the first recorded hangover … One thing we innovative humans are good at is looking for cures to what ails us. But hangovers are a tricky study. According to Dr. Jason Burke, founder of Hangover Heaven and a “leading hangover expert” (it’s still a small field), most studies only allow participants to reach a blood alcohol level of 0.1, which is “not that high” for research purposes. (Ethics committees that approve scientific studies rightly consider BACs above that to be too risky.) Likewise, most studies need a control group, which can be hard to find when age, genetics, weight, and many other factors play into how each individual experiences a hangover.

Today, humanity has settled on aspirin and electrolyte-filled sports drinks to ease the pain. But in the past, food was often what came to the rescue.

Some of the more primitive hangover remedies were unpleasant, then as now. Eater.com described hangover cures ranging from purely superstitious to actively unpalatable:

Early hangover cures seem to fall into two categories: sounding like a way to keep vampires away and a meal worthy of Fear Factor. One recently uncovered Egyptian medical papyri advocated for making a garland out of the chamaedaphne shrub. The Greeks recommended wearing a careful selection of plants on your head to keep drunkenness at bay. Most of the plants associated with the god Dionysus — ivy, laurel, and asphodel — were used for medicinal purposes. Whether the plant mythology or hangover treatment came first is impossible to know for sure. Shrubbery not your thing? In ancient times, you could have also cast a spell over your beers before drinking them. Or only drink alcohol after a frog drowned in it. Whether the frog had to drown accidentally or whether the drinker-to-be was expected to lend a hand is open for interpretation.

[..]

Another less-appetizing hangover remedy is rabbit dung tea. Today, gardeners advocate giving plants some extra nutrients by steeping bunny poop in hot water and giving the greens a guzzle. (Like any good manure source, there’s a lot of good nitrogen, potassium, and minerals.) American cowboys (reportedly) decided it would be a better idea to just drink it themselves to make their aches go away.

Eater.com’s deep-dive didn’t mention asparagus specifically, but that didn’t mean there was no information about asparagus for hangovers.

What Causes a Hangover?

To understand how best to alleviate a hangover, understanding which bodily functions lead to the related symptoms was helpful.

A MayoClinic.com entry on hangovers helpfully stated in a section titled “Causes” that a hangover is caused “by drinking too much alcohol.” A subsequent list of bullet points was a bit more detailed, though:

A single alcoholic drink is enough to trigger a hangover for some people, while others may drink heavily and escape a hangover entirely.

Various factors may contribute to a hangover. For example:

- Alcohol causes your body to produce more urine. In turn, urinating more than usual can lead to dehydration — often indicated by thirst, dizziness and lightheadedness.

- Alcohol triggers an inflammatory response from your immune system. Your immune system may trigger certain agents that commonly produce physical symptoms, such as an inability to concentrate, memory problems, decreased appetite and loss of interest in usual activities.

- Alcohol irritates the lining of your stomach. Alcohol increases the production of stomach acid and delays stomach emptying. Any of these factors can cause abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting.

- Alcohol can cause your blood sugar to fall. If your blood sugar dips too low, you may experience fatigue, weakness, shakiness, mood disturbances and even seizures.

- Alcohol causes your blood vessels to expand, which can lead to headaches.

- Alcohol can make you sleepy, but it prevents deeper stages of sleep and often causes awakening in the middle of the night. This may leave you groggy and tired.

In the first bullet point, Mayo Clinic described a primary cause for hangovers — alcohol’s diuretic effect, stimulating increased urine production and thus exacerbating dehydration. Additional factors on the list were inflammation, stomach irritation, a drop in blood sugar, blood vessel dilation, and sleep disruptions.

The entry also mentioned “congeners,” byproducts of fermentation including methanol, other alcohols, acetone, acetaldehyde, esters, tannins, and aldehydes. It also mentioned that alcoholic beverages containing fewer congeners are slightly less likely to cause hangovers than beverages with more congeners.

Noting that the only guaranteed way to prevent a hangover is to “avoid alcohol,” its “Prevention” section suggested hydration, slow pace consumption of alcohol, and conditional usage of over-the-counter painkillers like aspirin or ibuprofen as hangover remedies (taking care with the latter to avoid liver damage when combined with alcohol.)

Asparagus was not mentioned in the entry.

Why ‘Asparagus for Hangovers’ is a December News Staple

A December 29 2020 Popular Science listicle (“6 tricks for avoiding a hangover,” an optimistic headling that was immediately undermined by its subtitle, “Maybe”) began by explaining that hangovers are somewhat poorly understood, a factor hampering the discovery of “cures”:

After thousands of years of getting wasted, humans still aren’t sure exactly what causes hangovers. The best, most scientifically sound guess is that it’s some combination of dehydration, the chemicals left behind when your body metabolizes alcohol, and plain-old divine punishment. In any case, not knowing the exact cause makes finding a “cure” difficult.

To make matters worse, it’s difficult to properly test any proposed remedies. After sifting through 281 papers on hangover treatments, a 2005 analysis in the British Medical Journal found a whopping 8 legit (randomized, controlled) experiments. Based on those 8 studies, the researchers concluded, no substance has proven itself effective at preventing or treating a hangover. Still, a cure may be out there, just waiting to be found and rigorously studied.

Per Popular Science, a 2005 analysis of 281 papers turned up only eight reliable studies — along with a conclusion that “no substance” has been deemed fully effective at hangover prevention or treatment. However, among bits of advice similar to the Mayo Clinic’s (hydration; choosing your alcoholic beverages carefully), the organization added:

Eat asparagus

A 2009 study in the Journal of Food Science suggests that the amino acids and minerals in asparagus may protect your liver cells. The experiment was done in a petri dish on cells that were presumably not actually drunk, but feel free to perform your own in vivo experiment. At the very least, eating asparagus before a night out should increase your dietary fiber and vitamin A and C levels. Of course, it’ll also make your pee smell weird, which might not make you feel any perkier the next morning.

Both the tag in the image and the quoted excerpt above mentioned that asparagus might “protect your liver cells,” but the “various factors” in the causes list above didn’t mention liver cells as a contributing factor specific to hangovers — although the article specifically advised eating asparagus before drinking, not after. Conversely, the 2005 analysis cited was published four years before the 2009 study cited by Popular Science, making it possible asparagus would have made the list as a ninth “cure.”

On December 31 2012, NBC News published, “Eat asparagus, and more questionable ways to ease your hangover,” establishing a trend — news articles and content about hangovers appeared to be a perennial topic on the days just prior to (and on) New Year’s Eve. The latter factor might explain why the same 2009 Journal of Food Science paper was cited by NBC News three years after it appeared, since it wasn’t new news.

Alongside pickle juice and prickly pear, asparagus for hangovers was charitably damned with faint praise:

While the experts agree — and, really, most of us know — that abstaining from alcohol or drinking less is the only surefire way to prevent a hangover, if you must imbibe tonight, here are a few foods people often use to lessen the pains the day after drinking.

Pass the asparagus: In 2009, researchers in South Korea published a paper saying that eating asparagus before drinking prevents those icky hangover feelings.

“There is a little tidbit of truth to it … not that I would discourage people from eating asparagus,” explains Leslie Bonci, director of sports nutrition at UPMC Center for Sports Medicine in Pittsburgh, adding that bingeing on asparagus the night before drinking will do nothing for a headache the next day.

But asparagus might protect the body from booze. The amino acids in asparagus improve how quickly human cells break down alcohol, preventing some long term damage from toxic byproducts of alcohol such as hydrogen peroxide.

“Whether other or not these effects will actually make a human feel any better remains to be seen,” writes Dr. Rachel Vreeman, co-author of “Don’t Swallow Your Gum! Myths, Half-Truths, and Outright Lies about Your Body and Health,” in an email. “It is not clear that these amino acids, or amino acids from other good sources like eggs, will actually help a person with a hangover feel any better.”

NBC News cited the same 2009 study about asparagus, but a nutrition expert consulted for the article explicitly said that “binging on asparagus” prior to drinking will do nothing to prevent a headache, or anything else, the morning after. A second expert effectively said there was no reason to think the cited benefit of asparagus could actually help at all.

Business Insider covered asparagus for hangovers on December 27 2012, with the headline, “Asparagus As A Hangover Cure?” That ended with a question mark, evoking a neo-adage coined for journalist Ian Betteridge in 2009 — Betteridge’s Law of Headlines:

Betteridge’s law of headlines is an adage that states: “Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.” It is named after Ian Betteridge, a British technology journalist who wrote about it in 2009, although the principle is much older. The adage fails to make sense with questions that are more open-ended than strict yes–no questions.

[…]

Betteridge’s name became associated with the concept after he discussed it in a February 2009 article …

This story is a great demonstration of my maxim that any headline which ends in a question mark can be answered by the word “no.” The reason why journalists use that style of headline is that they know the story is probably bullshit, and don’t actually have the sources and facts to back it up, but still want to run it.

As noted in the excerpt above, “open-ended questions” are sometimes seen as exempt, versus “strict yes-no questions.” (We also would like to point out that fact-checking articles often follow slightly different conventions.) The Business Insider article began:

Doctors and other medical professionals have long claimed there’s no such thing as a hangover cure, but a study from 2009 suggests that the vitamins and minerals in green vegetables like asparagus could mediate the toxicity that alcohol inflicts on your liver during a night of drinking.

Supposedly this is an old wives tale (I’ve never heard it though).

While this particular article described the asparagus hangover cure as an “old wives tale,” it also led with the specific described function that purportedly prevents them — liver-protecting enzymes. But the 2012 piece also said of the study:

[Study authors] don’t mention if you should be taking in the vegetable before, during or after the drinking. Based on what they are saying the mechanism is, I’d say it could have a positive impact either way, though it might be the best if taken before.

The study was published in the Journal of Food Science, in September of 2009. It’s making the news now because of a press release from the Institute of Food Technologists, released Dec. 26. [2012].

The Asparagus Hangover Study

A press release about the 2009 asparagus hangover study was indeed distributed on December 26 2012 — hinting that researchers were also aware journalists were likely to come knocking in the lead-up to New Year’s Eve for hangover remedies. The press release, “Eating Asparagus May Prevent a Hangover,” summarized its findings for interested parties:

Drinking to ring in the New Year may leave many suffering with the dreaded hangover. According to a 2009 study in the Journal of Food Science, published by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), the amino acids and minerals found in asparagus extract may alleviate alcohol hangover and protect liver cells against toxins.

Researchers at the Institute of Medical Science and Jeju National University in Korea analyzed the components of young asparagus shoots and leaves to compare their biochemical effects on human and rat liver cells. “The amino acid and mineral contents were found to be much higher in the leaves than the shoots,” says lead researcher B.Y. Kim.

Chronic alcohol use causes oxidative stress on the liver as well as unpleasant physical effects associated with a hangover. “Cellular toxicities were significantly alleviated in response to treatment with the extracts of asparagus leaves and shoots,” says Kim. “These results provide evidence of how the biological functions of asparagus can help alleviate alcohol hangover and protect liver cells.”

Asparagus officinalis is a common vegetable that is widely consumed worldwide and has long been used as an herbal medicine due to its anticancer effects. It also has antifungal, anti-inflammatory and diuretic properties.

The press release linked to an abstract (and paper) for the single source trotted out each year in hangover listicles, published in September 2009 in the Journal of Food Science and titled “Effects of Asparagus officinalis Extracts on Liver Cell Toxicity and Ethanol Metabolism.” The abstract read:

ABSTRACT: Asparagus officinalis [asparagus] is a vegetable that is widely consumed worldwide and has also long been used as a herbal medicine for the treatment of several diseases. Although A. officinalis is generally regarded as a supplement for the alleviation of alcohol hangover, little is known about its effects on cell metabolism. Therefore, this study was conducted to analyze the constituents of the young shoots and the leaves of asparagus and to compare their biochemical properties. The amino acid and inorganic mineral contents were found to be much higher in the leaves than the shoots. In addition, treatment of HepG2 human hepatoma cells with the leaf extract suppressed more than 70% of the intensity of hydrogen peroxide (1 mM)-stimulated DCF fluorescence, a marker of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Cellular toxicities induced by treatment with hydrogen peroxide, ethanol, or tetrachloride carbon (CCl4) were also significantly alleviated in response to treatment with the extracts of A. officinalis leaves and shoots. Additionally, the activities of 2 key enzymes that metabolize ethanol, alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase, were upregulated by more than 2-fold in response to treatment with the leaf- and shoot extracts. Taken together, these results provide biochemical evidence of the method by which A. officinalis exerts its biological functions, including the alleviation of alcohol hangover and the protection of liver cells against toxic insults. Moreover, the results of this study indicate that portions of asparagus that are typically discarded, such as the leaves, have therapeutic use.

Subsequently, the paper described the methodology of the research — which seemed a lot less fun than what we had originally imagined. Researchers explained that cultured Hep G2 liver cells in tissue culture dishes formed the “liver” element of the research, and said of the asparagus samples and the commercially available hangover remedies freeze dried and used as control samples:

A. officinalis was obtained from several different farms in the Jeju region of Korea and the young shoots and leaves were removed and air-dried at room temperature. The dried samples (100 g) were then extracted with 1 L of boiling distilled water for 2 h at 100 °C and then the extracts were passed through a Whatman GF/C filter. The hot water extracts were then freeze-dried and stored at –20 °C until use. Two commercial hangover drinks (HOD1, Condition™, CJ, Korea; HOD2, Dawn808™, Glami, Korea) were also freeze-dried and used as positive controls to compare to the effects of the extracts of A. officinalis.

The study’s conclusion read in full:

The results of this study demonstrate that the extract of the leaves of A. officinalis contained a higher level of amino acids and minerals than those of the young shoots. Furthermore, the extracts of asparagus were found to exert potent cytoprotective properties, including a strong, wide range of antioxidant activities in HepG2 cells. The extracts of asparagus also promoted activities of ADH and ALDH in the enzymatic assay using liver cell homogenate as an enzymatic source. Thus, the leaves of A. officinalis, which are normally discarded, have the potential for use in therapy designed to protect the liver from various harmful insults.

It is true that the entirety of the research mentioned commercially available hangover cures (and that researchers included hangovers in the scope of this specific asparagus study), but the conclusion only stated that asparagus had the potential for use in therapy designed to protect the liver” from injury. No portion of the research involved recommendations for the consumption of asparagus prior to drinking (as the tag indicated) to prevent a hangover, nor did it recommend eating asparagus after drinking to ameliorate hangover discomfort.

Summary

New organizations run “hangover cure” listicles around the end of each year; a December 26 2012 press release effectively pitched asparagus as a hangover cure to journalists interested in reporting the results of a September 2009 Journal of Food Science study titled “Effects of Asparagus officinalis Extracts on Liver Cell Toxicity and Ethanol Metabolism.” After several listicles cited the study across several Decembers, it predictably showed up in marketing materials for a Canadian produce supplier, which were later uploaded to Imgur. Readers seeking citations were likely to come across articles citing the study and adopting an “it can’t hurt” approach, alongside a decent amount of wobbly disclaimers about it being unclear how to consume asparagus to avoid hangovers. As such, we rated the claim Decontextualized, since factors contributing to its popularity included advertising by produce companies and journalists doing late December hangover pieces every year.

- Asparagus for Hangovers | Imgur

- 'Want to Avoid a Hangover? Eat Asparagus!' | Welsh Bros. Ontario

- The Weird and Wonderful History of Hangover Cures

- Hangovers

- 6 tricks for avoiding a hangover

- Eat asparagus, and more questionable ways to ease your hangover

- Asparagus As A Hangover Cure?

- Betteridge's law of headlines

- Eating Asparagus May Prevent a Hangover

- Effects of Asparagus officinalis Extracts on Liver Cell Toxicity and Ethanol Metabolism