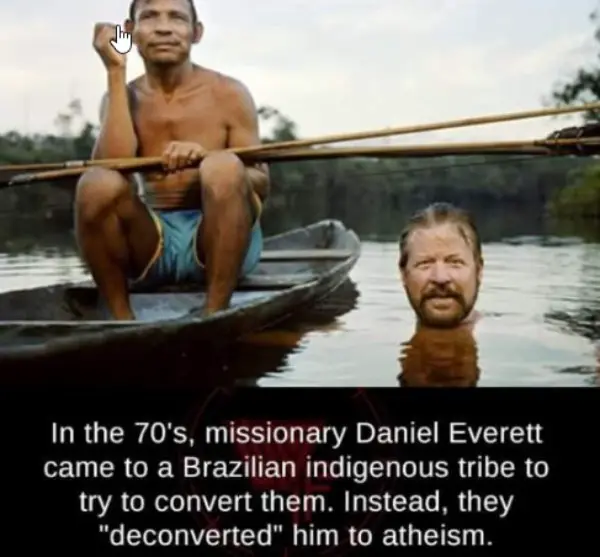

A former evangelist’s journey to becoming an advocate for a tribe native to the Brazilian Amazon rainforest has endured not only through his own efforts, but through the reproduction online of a famous photograph of him.

In October 2019, a Reddit post summarizing Daniel Everett’s experience with the Pirahã tribe (pronounced “pee-da-HAN”) was highlighted and shared thousands of times on the platform. It included a graphic of a photo taken of him by Martin Schoeller:

The caption reads:

In the 70s, missionary Daniel Everett came to a Brazilian indigenous tribe to try to convert him. Instead, they “deconverted” him to atheism.

While it has been streamlined and simplified, the story is correct; according to a story on him in the Guardian published in 2008, Everett spent all of 1980 living with the Pirahã, and for the following two decades he spent at least four months every year with them. He told the newspaper that by 1985, he had come to adopt the tribe’s worldview and said that attempting to convert indigenous communities in and of itself was wrong:

What should the empirical evidence for religion be? It should produce peaceful, strong, secure people who are right with God and right with the world. I don’t see that evidence very often. So then I find myself with the Pirahã. They have all these qualities that I am trying to tell them they could have. They are the ones who are living life the way I’m saying it ought to be lived, they just don’t fear heaven and hell.

A year later, at the national convention for the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Everett shared more anecdotes from his life with the Pirahã:

I built up gradually the ability to translate parts of the bible, and I read to them my translation of part of the Gospel of John one night, and I gave them my testimony. And as you know — anybody who’s got the remotest connection with the Christian church — giving a testimony is supposed to be a powerful thing. You talk about how once I was blind and now I see, how I went from this very bad background to this very good person that I am today.

So I gave them my testimony and I told them about my stepmother committing suicide. When I got done telling them, they all burst out laughing, and I said, “What are you laughing about?” I was really hurt. “Why are you laughing?” They said, “We don’t kill ourselves. You people kill yourselves? What is this?”

Everett’s experience with the tribe also drew him into a disagreement with academic Noam Chomsky. According to Everett, the Pirahã language refutes the theory of “universal grammar.” As the Guardian summarized:

In 2005, Everett published a paper about the Pirahã that rocked the foundations of universal grammar. Chomsky had recently refined his theory to argue that recursion — the linguistic practice of inserting phrases inside others — was the cornerstone of all languages. (An example of recursion is extending the sentence “Daniel Everett talked about the story of his life” to read, “Daniel Everett flew to London and talked about the story of his life”.) Everett argued that he could find no evidence of recursion in Pirahã. This was deeply troubling for Chomsky’s theory. If the Pirahã didn’t use recursion, then how could it be a fundamental part of a universal grammar embedded in our genes? And if the Pirahã didn’t use recursion, then is their language — and, by implication, other languages — determined not by biology but by culture?

In January 2017, Everett, now a professor of cognitive sciences at Bentley University in Massachusetts, reflected on the dispute in an op-ed for Aeon magazine.

“If recursion is just a component of human intelligence generally, even if it were the fact of human intelligence, then it is available to be used or not used by human languages,” he wrote. “It isn’t the narrow faculty of language. It is the way humans think. And we have no strong evidence that we are the only creatures that can think recursively.”