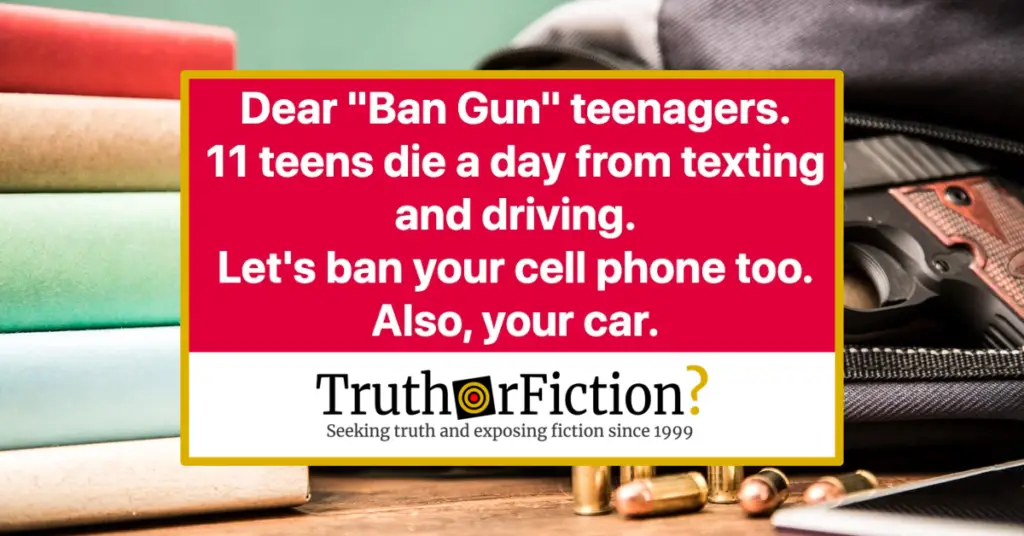

Facebook status memes about guns in general consistently appear in the now nearly constant wake of mass shootings, but a February 2018 iteration (archived here) aimed at “‘ban gun’ teenagers” puts forth an insincere argument targeting texting and driving instead:

Posted just eleven days after 17 people were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, white text against a red background reads:

Dear “Ban Gun” teenagers.

11 teens die a day from texting and driving.

Let’s ban your cell phone too.

Also, your car.

This widely-shared post was shared at a time when the grieving and traumatized students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas had just begun speaking out about the events of the shooting before galvanizing one of the largest marches in American History. A March 2018 event known as March for Our Lives drew between one and two million Americans to Washington, D.C., calling for action in relation to the previous month’s massacre.

Much of the context of this commentary aligns with a previous fact check of ours, in which a similar text-based status update image claimed to contrast gun deaths with drunk driving fatalities to argue against then-recent gun policies enacted by mega-retailer Walmart.

As with our previous fact-check, this rumor employed whataboutism by pointing to another cause of death — texting and driving. According to the meme, eleven teenagers die each day due to texting and driving, thus the Parkland students ought to “ban” both cell phones and vehicles instead of guns. And as is commonly the case with Facebook posts of this format, a number of inaccuracies were crammed into a relatively concise statement without context or citation.

The post begins by addressing “‘ban gun’ teenagers” — but the reforms sought by the Parkland teenagers were not accurately summarized as “ban guns.” They in fact proposed nine detailed changes to gun policy, not one of which was “ban guns.” One involved banning a specific class of firearms, but the remaining eight changes involved databases, background checks, loopholes, research, and various related policies:

- Ban semi-automatic weapons that fire high-velocity rounds;

- Ban accessories that simulate automatic weapons;

- Establish a database of gun sales and universal background checks;

- Change privacy laws to allow mental healthcare providers to communicate with law enforcement;

- Close gun show and secondhand sales loopholes;

- Allow the CDC to make recommendations for gun reform;

- Raise the firearm purchase age to 21;

- Dedicate more funds to mental health research and professionals;

- Increase funding for school security

By inaccurately summarizing their position as “ban guns” the poster and sharers arguably engaged in a strawman fallacy, dishonestly framing their position to make it easier to attack. For some reason, “‘fund the CDC’ teenagers” doesn’t have the same rhetorical effect.

Moving on, the post claimed eleven teenagers die each day due to texting and driving; presumably the total number of people killed in all texting and driving incidents would then be far higher in proportion to the total population. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) compiles statistics using ten age groupings [PDF] (<1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, and 65+), with all teenagers falling across two of the ten (10-14 and 15-24).

Teenagers make up 13 percent of Americans as of February 2019, according to Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) statistics; this means that 87 percent of living Americans were not teenagers. If the teenaged 13 percent of Americans who died in texting and driving accidents daily totaled eleven, then we could estimate 84.6 total deaths per day from the same cause, assuming all age groups are equally likely to be in scenarios in which a texting driver may cause an accident.

However, according to the CDC, nine (not eleven) Americans in total of all age groups die each day in texting and driving related accidents. That number includes teenagers, parents, the elderly, and all others who are either in a vehicle with a driver texting or struck by a vehicle whose driver was texting. Consequently, the claim that eleven teenagers alone died from texting and driving is by any metric completely false and misleading. If we apply the 13 percent figure to determine how many of the nine Americans are teens, we arrive at a figure of 1.17 teenager deaths a day from texting and driving.

Bringing the comparison into fair and broader context, 39,773 Americans died of gun-related causes in 2017, the most recent year for which complete statistics are available via the CDC. When we average that over 365 days a year, approximately 109 Americans in all ten age groups die each day of gun-related causes. If we once again break it further down to the 13 percent of the population who are teenagers, 14 teenagers died daily of gun-related causes on average — versus 1.17 in texting and driving accidents.

The Facebook post makes no mention of gun-related deaths as it claims that an out-of-context, incorrect number of texting and driving-related deaths are a better focus for advocacy than gun policy for concerned teenagers. The post thus is now a form of cherry picking, because it omits the far higher number of annual gun deaths (39,773) in favor of solely presenting the number of deaths from an unrelated cause (texting and driving, actually nine total deaths).

Overall, the meme was half purported statement of fact (“eleven teenagers die daily due to texting and driving”) and half opinion. We cannot fact-check the latter. People are free to support or oppose any and all gun control, but they need not misrepresent statistics or introduce red herrings to do so. In fact, in a one-to-one comparison based on available statistics provided by the CDC, 1.17 teenagers died daily due to texting and driving, while 14 died daily due to guns.

Presented in its complete context, the post’s premise is far less compelling.