On September 17 2020, the following post was shared to r/therewasanattempt, which described a purported initiative to curb suicides on South Korea’s Mapo Bridge:

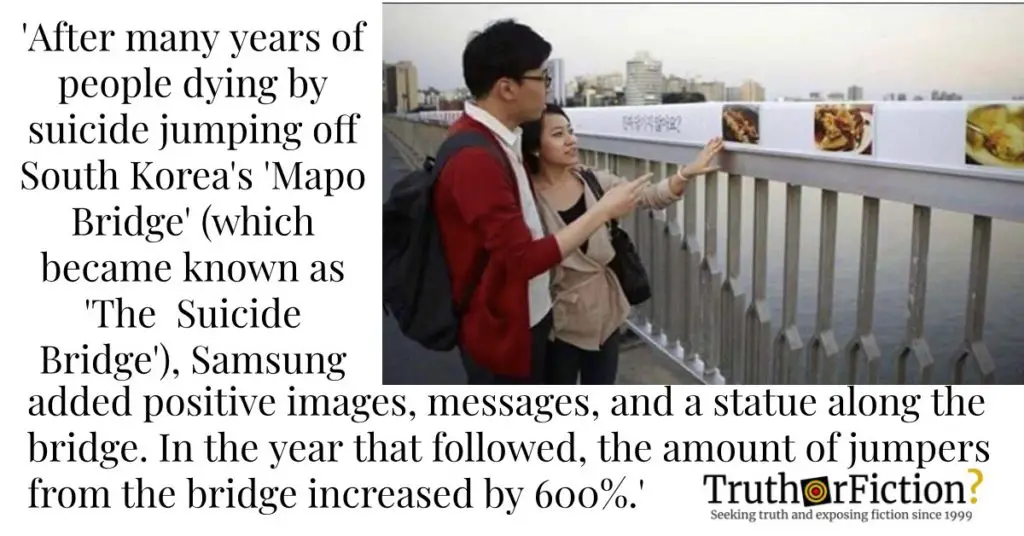

An image showed two individuals standing on a bridge with the the following text:

After many years of people committing suicide by jumping off South Korea’s ‘Mapo Bridge’ (which became known as ‘The Suicide Bridge’), the Samsung Life Insurance company renamed it ‘The Bridge of Life’. In an effort to stop people from jumping, Samsung added positive images, messages, and even a statue along the bridge. In the year that followed, the amount of jumpers from the bridge increased by 600%.

No citations or sources for the image or its claims were included, and discourse on the thread largely involved users’ opinions about the purportedly unsuccessful campaign.

Mapo Bridge and South Korea’s Overall Rate of Death by Suicide

Mapo Bridge has a reputation as a common site for deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. A 2012 Reuters story details the efforts to curb the troubling trend:

South Korea’s suicide rate has been the highest among developed nations for the past eight years, with almost 43 people choosing to end their lives every day.

The Mapo Bridge, one of 25 over the capital’s river, has seen 108 suicide attempts in the past five years but authorities aim to bring that down by placing signs along it with messages such as: “the best part of your life is yet to come”.

An undated Washington Post chart, “World suicide rates by country,” used data for the year 2005 and described South Korea as having the highest rate of suicide according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). That chart indicated that in 2005, South Korea had 24.7 suicides per 100,000 residents; Hungary had 21, Japan had 19.4, Belgium had 18.4, and Finland had 16.5.

A 2018 piece by U.S. News and World Report ranked South Korea as having the fourth highest rate of suicide globally, using data from 2016. As of 2016, the rate of suicide per 100,000 people rose from 24.7 in 2005 to 26.9:

South Korea recorded the fourth-highest rate of suicide, according to the World Health Organization data. The small East Asian state reported 26.9 suicides for both genders per 100,000 people in 2016. Men are at a higher risk of committing suicide with a rate of 38.4 deaths per 100,000 people, while women recorded a rate of 15.4 deaths per 100,000. Causes of suicide in Korea vary, but are mainly related to stress, and is rapidly affecting more adolescents and the elderly.

In December 2019, Nikkei Asian Review reported that a rash of suicides among Korean pop (K-Pop) stars prompted concerns about copycat deaths. That item indicated the rate of suicide per 100,000 people peaked in 2011 at 31.7, and that the government exercised initiatives to prevent deaths:

Suicide is not uncommon in South Korea. The country has the highest suicide rate among the members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. According to the OECD, its suicide rate per 100,000 people is 24.6. That is twice as high as the average among the member states and far higher than Japan’s 15.2.

The high rate cannot be attributed to a single factor, but structural changes in South Korean society play a part. There has been a surge of nuclear families since the 1990s, and more and more elderly people are living alone. The pace of the increase has outpaced efforts to build social safety nets. The suicide rate among senior citizens exceeds 50 per 100,000.

South Koreans sometimes kill themselves as a way to protest, apologize or solve a problem, so self-inflicted death is not perceived as an entirely bad thing. Another reason is strong prejudice against mental illness, which makes it hard for people to seek medical treatment.

The government has issued suicide prevention basic plans three times since 2004 and taken measures such as opening suicide prevention centers, helping install platform doors at subway stations and banning the production and sale of highly toxic agrochemicals. The rate has fallen from the 2011 peak of 31.7.

But the impact of celebrity suicides could ruin these efforts.

Samsung Life Insurance’s Mapo ‘Bridge of Life’ Project

In 2013, a number of outlets reported on efforts in September 2012 to “transform” Mapo Bridge by using positive, insiprational messages and images:

And one bridge over the Han River, the Mapo Bridge, has been dubbed the Bridge of Death for its unfortunate popularity among those seeking to end their own life. Between 2007 and 2012, more than 100 people attempted suicide from the Mapo Bridge.

To try to counteract the number of deaths from the bridge, the Seoul City government didn’t build a high fence or suicide barrier; instead, it teamed with Samsung Life Insurance to take a different path, adding interactive handrails that speak directly to passersby.

The handrails use motion sensors to sense people’s movements and then light up with short inspirational messages crafted with the help of psychologists and suicide prevention specialists, as well as photos of happy families and individuals.

Reporting suggested that the efforts were successful, despite some criticism that the project’s features might exacerbate suicidal ideation:

Some have criticized the bridge, believing that photos of families could trigger someone who was deeply missing a deceased family member … However, according to the Seoul City government, the suicide rate from Mapo Bridge has dropped 77 percent since the revamped design was unveiled last September and the bridge is now one of the city’s most popular walking spots.

In June 2013, coverage of the changes to Mapo Bridge cited that statistic repeatedly:

[Positive] messages were carefully curated by a team of psychologists and suicide prevention specialists, and the effort seems to be paying off. The Seoul City government says suicides on the bridge have dropped by a whopping 77 percent since the changes were made, and the bridge has now become a popular tourist attraction. Similar actions are being planned for other spans in the area.

Reporting on changes to the bridge was generally upbeat, noting that the “messages were carefully crafted after consulting with psychologists and suicide-prevention activists.”

Outcome

A September 2014 piece written by DJ Jaffe of the Mental Illness Policy Org (who died in August 2020; his obituary, which ran on September 16 2020, may have re-ignited interest in this issue) addressed similar initiatives and their efficacy in curbing rates of suicide:

There is little scientific evidence media campaigns reduce suicide and mounting evidence they don’t. The largest and most sound review of the issue was Suicide Prevention Strategies: A systematic review, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. (J. John, Alan and al. 2005). The authors found that

despite their popularity as a public health intervention, the effectiveness of public awareness and education campaigns in reducing suicidal behavior has seldom been systematically evaluated.

The report went on to note what the research does show:

Such public education and awareness campaigns, largely about depression, have no detectable effect on primary outcomes of decreasing suicidal acts or on intermediate measures, such as more treatment seeking or increased antidepressant use.

A 2009 study in the journal Psychiatric Services looked at 200 publications between 1987 and 2007 describing depression and suicide awareness programs targeted to the public and found that the programs “contributed to modest improvement in public knowledge of and attitudes toward depression or suicide,” but could not find that the campaigns actually helped increase care seeking or decrease suicidal behavior. A similar study in 2010 in the journal Crisis actually found that billboard ads had negative effects on adolescents, making them “less likely to endorse help-seeking strategies”. (Sanburn 2013)

In February 2014, an English-language Asian news organization reported that the efforts appeared to have little effect on the rate of suicide between September 2012 and February 2014:

Initial hopes were high for the Bridge of Life Project, which was lauded with some 37 advertising and PR awards. Unfortunately, despite the widely accepted soundness of its theories, suicides at Mapo Bridge have risen dramatically since the project’s beginning. 2013 saw 93 such tragedies take place on the bridge, more than six times as many as in the previous year.

Experts feel that rather than offering encouragement to the emotionally unstable, the messages placed on the bridge have instead fed into Mapo Bridge’s unfortunate image as a place where people go to end their own lives. The tragic association is unlikely to be uncoupled anytime soon, and in light of the sobering results of the first full calendar year of the Bridge of Life Project, a growing number of people are calling for physical, rather than mental, countermeasures, such as glass walls and nets to prevent or catch jumpers.

In October 2019, Korea Biz Wire reported that all slogans and imagery were eventually removed from the bridge, and replaced with a new fence in December 2016:

Slogans printed on the guardrail that runs along the pedestrian walkway at Seoul’s Mapo Bridge to help people think twice about committing suicide have all been taken down, seven years after they were originally installed … all of the slogans inscribed on the guardrail at Mapo Bridge were removed on October 8 and 9 [2019].

The anti-suicide slogans were first inscribed on the bridge in 2012 as part of the ‘Bridge of Life’ campaign launched by the city and Samsung Life Insurance Co.

[…]

“A new fence was installed in December 2016 to prevent people from jumping off the bridge, which has further deprived the slogans of any use. In many cases, the remaining slogans only seemed to confuse people,” said a city official.

Between 2014 and 2018 … a total of 846 people jumped off the bridge, with 24 people killed, during this period.

We were unable to find any information about other factors that may have contributed to the overall suicide rate in that particular location, and in general, causes for suicide or attempted suicide are complex and individuated.

Summary

Although the claim presented in the Reddit post was more complex than it appeared, the basic facts presented were true. In late 2012, Samsung Life Insurance was one of a few parties which endeavored to reduce the rate of suicide on South Korea’s Mapo Bridge by installing positive and inspirational messages. Initial reports claimed the rate of suicide dropped by 77 percent, but later reporting indicated the rate of suicide on Mapo Bridge had, as of early 2014, increased rather than decreased. As of October 2019, all traces of the “Bridge of Life” initiative were gone, replaced with a fence.

- to stop suicide

- Mapo Bridge

- World suicide rates by country

- Countries With the Highest Rates of Suicide

- K-pop deaths spark fear of copycat suicides in South Korea

- 'Bridge of Life' projects messages to prevent suicides

- Seoul's Bridge of Life curbs suicide attempts with happy thoughts

- The Bridge of Life by Samsung Life Insurance Touches the Heart

- Samsung Bridge of Life

- Preventing suicide in all the wrong ways

- Seoul anti-suicide initiative backfires, deaths increase by more than six times

- Slogans for Suicide Prevention Removed from Mapo Bridge After 7 Years