In August 2019, disinformation and misinformation about the history of immigration to the United States flourished online following the announcement that United States President Donald Trump’s administration would pursue the so-called “public charge” standard as a means to curb immigration into the country. Much of that disinformation online concerns the history of public assistance programs in the country, and it is almost entirely wrong.

The new rule was announced by the United States Customs and Immigration Services’ acting director Ken Cuccinelli, perhaps best known before this appointment for his time as Virginia’s attorney general advocating for transvaginal ultrasounds for women seeking abortions and for 2012 comments comparing immigrants to rats. It is the finalization of a policy the Trump administration first proposed in September 2018.

The new rule is slated to go into effect on 15 October 2019, and it would allow the administration to deny immigrants entry into the United States if it is deemed that they are likely to use services such as Section 8 rental or housing aid, Medicaid, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program “for more than 12 months in the aggregate within any 36-month period” at any point after entering the United States:

This final rule amends DHS regulations by prescribing how DHS will determine whether an alien is inadmissible to the United States based on his or her likelihood of becoming a public charge at any time in the future, as set forth in the Immigration and Nationality Act. The final rule addresses U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) authority to permit an alien to submit a public charge bond in the context of adjustment of status applications. The rule also makes nonimmigrant aliens who have received certain public benefits above a specific threshold generally ineligible for extension of stay and change of status.

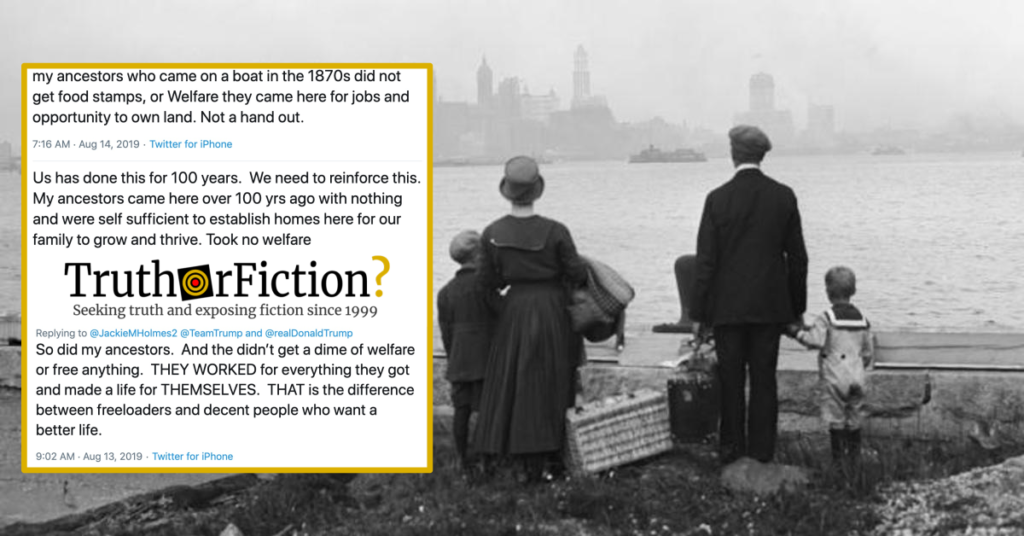

While the rule has already sparked a legal challenge from two counties in California, specious arguments that it is justifiable because “our ancestors” had no access to social assistance programs have proliferated online:

These arguments ignore the fact that emigrating to the United States was vastly less restricted prior to (and even in the years following) the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882; as one advocacy group, the American Immigration Council, noted in a 2016 report, “A growing, increasingly industrialized nation needed workers, and immigration was ‘encouraged and virtually unfettered.’ Potential immigrants did not have to obtain visas at U.S. consulates before entering the country.”

Some states offered incentives to entice new immigrants to settle in their region:

Although immigrants often settled near ports of entry, a large number did find their way inland. Many states, especially those with sparse populations, actively sought to attract immigrants by offering jobs or land for farming. Many immigrants wanted to move to communities established by previous settlers from their homelands.

The Homestead Act of 1862, which in a mighty case of wealth redistribution took land stolen from indigenous Americans and gave it to settlers, included new immigrants by design:

A homesteader had only to be the head of a household or at least 21 years of age to claim a 160 acre parcel of land. Settlers from all walks of life including newly arrived immigrants, farmers without land of their own from the East, single women and former slaves came to meet the challenge of “proving up” and keeping this “free land”. Each homesteader had to live on the land, build a home, make improvements and farm for 5 years before they were eligible to “prove up”. A total filing fee of $18 was the only money required, but sacrifice and hard work exacted a different price from the hopeful settlers.

[…]

With application and receipt in hand, the homesteader then returned to the land to begin the process of building a home and farming the land, both requirements for “proving” up at the end of five years. When all requirements had been completed and the homesteader was ready the take legal possession, the homesteader found two neighbors or friends willing to vouch for the truth of his or her statements about the land’s improvements and sign the “proof” document.

Anti-immigrant commentary online also fails to account for the existence of other social assistance programs in the United States since the country’s beginnings; as Stefan Riesenfeld, who would become a professor emeritus of law at the University of California-Berkeley, wrote in 1955:

….It is still of interest not only as an important milepost on the road of progress but as an irrefutable proof of the fact that society’s concern for its less fortunate members is one of the cornerstones of the American democratic tradition.

The American colonies first adopted the practice as an adaptation of England’s Poor Laws of 1601, which set aside funds to assist British subjects affected by an economic depression. As Virginia Commonwealth University’s Social Welfare History Project reported in 2011:

Essentially, the laws distinguished three major categories of dependents: the vagrant, the involuntary unemployed, and the helpless. The laws also set forth ways and means for dealing with each category of dependents. Most important, the laws established the parish (i.e.,local government), acting through an overseer of the poor appointed by local officials, as the administrative unit for executing the law.

The poor laws gave the local government the power to raise taxes as needed and use the funds to build and maintain almshouses; to provide indoor relief (i.e., cash or sustenance) for the aged, handicapped and other worthy poor; and the tools and materials required to put the unemployed to work.

A report published by the National Association of Social Workers in 2013 pointed out that colonial communities — themselves immigrants — adopted similar programs:

As early as 1632, town authorities assigned “overseers of the poor” to investigate poverty and problems such as physical and mental disabilities, crime, or vagrancy. Their tasks were to assess need, collect and distribute funds (from a combination of taxes, private donations, church collections), and decide the fates of needy or deviant townspeople. Work was required of all, and so almsgiving (poor relief) was meager, since people believed that it discouraged work and contributed to immorality. War veterans were exceptions: from as early as 1616, they, their survivors, and their dependents were allotted pensions, and by 1777 almost every colony had veterans’ benefits.

Even closer to the 20th century, it was still not uncommon for local governments to offer specialized pension programs covering teachers or members of their police and fire departments. According to the Social Security Administration:

The teachers’ pension plan of New Jersey, which was established in 1896, is probably the oldest retirement plan for government employees. By the early 1900’s, a number of municipalities and local governments had set up retirement plans for police officers and fire fighters. New York State and New York City set up retirement systems for their employees in 1920-the same year that the Civil Service Retirement System was set up for Federal employees.

Companies in the railroad and manufacturing industry, among others, also implemented retirement programs for their workers following the Industrial Revolution. The United States federal government, however, brought assistance programs to the federal level beginning in 1935 with the passage of the Social Security Act in August 1935, in response to the effects of the Great Depression — a system buoyed by immigrants.

- English Poor Laws: Historical Precedents of Tax-Supported Relief for the Poor

- USCIS Announces Final Rule Enforcing Long-Standing Public Charge Inadmissibility Law

- The Operation of the English Old Poor Law in Colonial Virginia

- Social Policy: History (Colonial Times to 1900)

- How Retirement Was Invented

- Historical Development

- The Formative Era of American Public Assistance Law

- How U.S. Citizens' Health Could Suffer Under Trump's New Rule Aimed at Immigrants

- California Counties File First Lawsuit Over Trump 'Public Charge' Rule

- Did My Family Really Come “Legally”?

- Can non-U.S. citizens receive Social Security benefits?

- Immigration and Social Security

- Immigration: Challenges for New Americans

- Rise of Industrial America: Immigration to the United States

- Indian Removal in the Midwest

- About the Homestead Act

- Homestead Act