As the 2018 midterms approached in the United States, the national conversation turned more and more toward the right to vote — and whether all Americans are truly able to exercise that right.

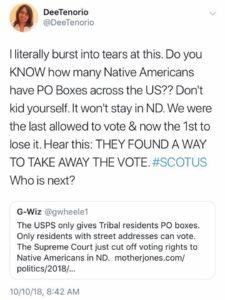

The conversation took a new turn just weeks before the November 6th election, when the Supreme Court declined to overturn a controversial North Dakota law that could effectively disenfranchise thousands of Native American voters by making identification that requires a street address (rather than, for example, a post office box) a requirement:

A group of Native American voters in North Dakota have challenged the law, telling the courts that the requirement that voters present identification bearing a street address could pose an obstacle to voting for Native Americans in several ways. Native Americans often live on reservations or in other rural areas where people do not have street addresses; even if they do, lawyers for the challengers argue, those addresses are frequently not included on tribal IDs. Moreover, the lawyers add, Native Americans in North Dakota are “disproportionately homeless.”

In April, a federal district court in North Dakota ordered the state to allow voters to cast ballots as long as they could show IDs that had either a current street address or a current mailing address, such as a P.O. box. The state followed that order in the June primaries, but in September the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit put the district court’s order on hold.

“The risk of voter confusion appears severe here because the injunction against requiring residential-address identification was in force during the primary election and because the Secretary of State’s website announced for months the ID requirements as they existed under that injunction,” noted Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her dissent:

Reasonable voters may well assume that the IDs allowing them to vote in the primary election would remain valid in the general election. If the Eighth Circuit’s stay is not vacated, the risk of disfranchisement is large.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, the move is likely to create major issues for people trying to vote in the midterm elections (which were less than a month away at the time of the ruling) because thousands of likely voters will probably not be able to produce any street address in time to cast a vote:

The Native American Rights Fund sued North Dakota in early 2016, arguing that the law was unconstitutional and a violation of the Voting Rights Act. A federal district judge agreed, issuing a ruling in April that blocked the ID requirement, but the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit overturned that ruling in a 2-1 decision in September. The Supreme Court’s denial of the Native American Rights Fund’s emergency appeal means that the law will stand, creating a huge amount of confusion for thousands of voters whose IDs were valid for the June primaries but are no longer adequate for them to vote on Nov. 6.

Jacqueline De León, staff attorneys for the Native American Rights Fund, said in a statement that the ruling appears to be an intentional effort to disenfranchise minority voters in a key state:

Access to voting should not be dependent on whether one lives in a city or on a reservation. The District Court in North Dakota has found this voter identification law to be discriminatory; nothing in the law has changed since that finding. North Dakota Native American voters will now have to vote under a system that unfairly burdens them more than other voters. We will continue to fight this discriminatory law.

Activists have created plans to counter the ruling’s effects on the midterm elections, including a push to create addresses for voters on the spot.

Tribal officials will stand outside polling stations on Nov. 6 with laptops and access to rural addressing software and a shared database of voter names. North Dakota is the only state that does not require voter registration, meaning eligible voters can generally show up at the polls and cast a ballot so long as they have proper identification.

O.J. Semans, chief executive of Four Directions, a national Native American voting rights group, said the strategy was “legally watertight” and necessary to counter the “devastating” court ruling.

“Even if it doesn’t change the overall result, it’s about fighting back,” Semans said. “We have to fight back.”

In one of the country’s least-populous states — and where Heitkamp, one of the Senate’s most endangered Democratic incumbents, eked out a victory of fewer than 3,000 votes in 2012 — the Supreme Court ruling could prove decisive.

A related rumor, that the most junior Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh cast the deciding vote, is false. That is invalidated in the very first paragraph of the court document:

The application to vacate the stay entered by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit on September 24, 2018, presented to JUSTICE GORSUCH and by him referred to the Court, is denied. JUSTICE KAVANAUGH took no part in the consideration or decision of this application.

- Howe, Amy. "Court stays out of North Dakota voting dispute."

- Mukpo, Ashoka. "Supreme Court Enables Mass Disenfranchisement of North Dakota’s Native Americans."

- Native American Rights Fund. "Decision to Change Voter Id Requirements on Eve of Election Allowed to Stand."

- United States Supreme Court. "Richard Brakebill, Et Al. v. Alvin Jaeger, North Dakota Secretary of State on Application to Vacate Stay."

- Pogrund, Gabriel and Sonmez, Felicia. "In Senate battleground, Native American voting rights activists fight back against voter ID restrictions."