In mid-March 2022, posts about a warrant officer named Hugh Thompson and his role in the My Lai massacre circulated on social media, including a tweet describing that time period as the 50-year anniversary of that incident:

My Lai Massacre Social Media Posts

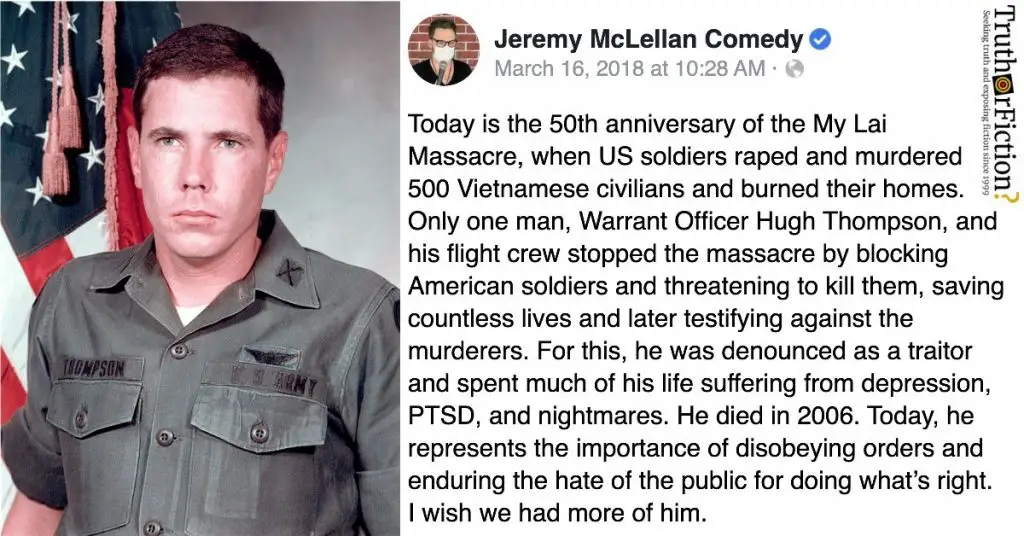

That tweet was published on March 20 2022. It included an Army photograph of a young man with the following text:

Fact Check

Claim: "Only one man, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, and his flight crew stopped the [My Lai] massacre by blocking American soldiers and threatening to kill them, saving countless lives and later testifying against the murderers."

Description: The claim suggests that Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson and his flight crew intervened during the My Lai massacre, an incident during the Vietnam War where American soldiers murdered Vietnamese civilians, by confronting his fellow soldiers and threatened to shoot them if they continued the massacre. As a result, he saved numerous lives that day, and testified against those involved in the massacre afterwards.

Today [March 20 2022] is the 50th anniversary of the My Lai Massacre, when US soldiers raped and murdered 500 Vietnamese civilians and burned their homes. Only one man, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, and his flight crew stopped the massacre by blocking American soldiers[.]

Both the image and text appeared to have been drawn from a popular Facebook post published on March 16 2018, four years before this tweet was shared. It also included the image:

Today [March 18 2018] is the 50th anniversary of the My Lai Massacre, when US soldiers raped and murdered 500 Vietnamese civilians and burned their homes. Only one man, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, and his flight crew stopped the massacre by blocking American soldiers and threatening to kill them, saving countless lives and later testifying against the murderers. For this, he was denounced as a traitor and spent much of his life suffering from depression, PTSD, and nightmares. He died in 2006. Today, he represents the importance of disobeying orders and enduring the hate of the public for doing what’s right. I wish we had more of him.

My Lai Massacre Background

The Facebook post was accurate, but the tweet was off by four years. History.com’s entry about the My Lai massacre began:

The My Lai massacre was one of the most horrific incidents of violence committed against unarmed civilians during the Vietnam War. A company of American soldiers brutally killed most of the people—women, children and old men—in the village of My Lai on March 16, 1968. More than 500 people were slaughtered in the My Lai massacre, including young girls and women who were raped and mutilated before being killed. U.S. Army officers covered up the carnage for a year before it was reported in the American press, sparking a firestorm of international outrage. The brutality of the My Lai killings and the official cover-up fueled anti-war sentiment and further divided the United States over the Vietnam War.

A PBS.org article about the My Lai massacre was similar, explaining:

On March 16, 1968 the angry and frustrated men of Charlie Company, 11th Brigade, Americal Division entered the Vietnamese village of My Lai. “This is what you’ve been waiting for — search and destroy — and you’ve got it,” said their superior officers. A short time later the killing began. When news of the atrocities surfaced, it sent shockwaves through the U.S. political establishment, the military’s chain of command, and an already divided American public.

Brittanica.com’s page about the incident provided detail about the events of the massacre, which was preceded by sustained conflict between American troops and the”48th Battalion, an especially effective Viet Cong unit operating in Quang Ngai province”:

Intelligence suggested that the 48th Batallion had taken refuge in the My Lai area (though in reality, that unit was in the western Quang Ngai highlands, more than 40 miles [65 km] away). In a briefing on March 15 [1968], Charlie Company’s commander, Capt. Ernest Medina, told his men that they would finally be given the opportunity to fight the enemy that had eluded them for over a month. Believing that civilians had already left the area for Quang Ngai city, he directed that anyone found in My Lai should be treated as a Viet Cong fighter or sympathizer. Under these rules of engagement, soldiers were free to fire at anyone or anything. Moreover, the troops of Charlie Company were ordered to destroy crops and buildings and to kill livestock.

Shortly before 7:30 AM on March 16, 1968, Son My village was shelled by U.S. artillery. The preparatory barrage was intended to clear a landing area for Charlie Company’s helicopters, but its actual effect was to force those civilians who had begun leaving the area back to My Lai in search of cover … By 7:50 AM the remainder of Charlie Company had landed, and [Lieutenant William] Calley led 1st Platoon east through My Lai. Although they encountered no resistance, the soldiers nonetheless killed indiscriminately. Over the next hour, groups of women, children, and elderly men were rounded up and shot at close range. U.S. soldiers also committed numerous rapes. Charlie Company’s 2nd Platoon moved north from the landing zone, killing dozens, while 3rd Platoon followed behind, destroying the hamlet’s remaining buildings and shooting survivors. At 9:00 AM Calley ordered the execution of as many as 150 Vietnamese civilians who had been herded into an irrigation ditch.

Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson

Brittanica.com later described the involvement of Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson:

As the massacre was taking place, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson was flying a scout helicopter at low altitude above My Lai. Observing wounded civilians, he marked their locations with smoke grenades and radioed for troops on the ground to proceed to those positions to administer medical aid. After refueling, Thompson returned to My Lai only to see that the wounded civilians subsequently had been killed. Spotting a squad of U.S. soldiers converging on more than a dozen women and children, Thompson landed his helicopter between the two groups. Thompson’s door gunner, Lawrence Colburn, and his crew chief, Glenn Andreotta, manned their weapons as Thompson hailed other helicopters to join him in ferrying the civilians to safety. In 1998 Thompson, Colburn, and Andreotta (posthumously) were awarded the Soldier’s Medal for acts of extraordinary bravery not involving contact with the enemy.

History.com also described Thompson’s intervention:

The My Lai massacre reportedly ended only after Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, an Army helicopter pilot on a reconnaissance mission, landed his aircraft between the soldiers and the retreating villagers and threatened to open fire if they continued their attacks.

“We kept flying back and forth … and it didn’t take very long until we started noticing the large number of bodies everywhere. Everywhere we’d look, we’d see bodies. These were infants, two- three-, four-, five-year-olds, women, very old men, no draft-age people whatsoever,” Thompson stated at a My Lai conference at Tulane University in 1994.

Thompson and his crew flew dozens of survivors to receive medical care. In 1998, Thompson and two other members of his crew received the Soldier’s Medal, the U.S. Army’s highest award for bravery not involving direct contact with the enemy.

Elements of the Facebook post about Thompson’s treatment and experiences after the incident were reflected in a Wikipedia page about Thompson, the introduction for which said in part:

During the massacre, Thompson and his Hiller OH-23 Raven crew, Glenn Andreotta and Lawrence Colburn, stopped a number of killings by threatening and blocking American officers and enlisted soldiers of Company C, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division. Additionally, Thompson and his crew saved a number of Vietnamese civilians by personally escorting them away from advancing United States Army ground units and assuring their evacuation by air. Thompson reported the atrocities by radio several times while at Sơn Mỹ. Although these reports reached Task Force Barker operational headquarters, nothing was done to stop the massacre. After evacuating a child to a Quảng Ngãi hospital, Thompson angrily reported to his superiors at Task Force Barker headquarters that a massacre was occurring at Sơn Mỹ. Immediately following Thompson’s report, Lieutenant Colonel Frank A. Barker ordered all ground units in Sơn Mỹ to cease search and destroy operations in the village.

In 1970, Thompson testified against those responsible for the Mỹ Lai Massacre. Twenty-six officers and enlisted soldiers, including William Calley and Ernest Medina, were charged with criminal offenses, but all were either acquitted or pardoned. Thompson was condemned and ostracized by many individuals in the United States military and government, as well as the public, for his role in the investigations and trials concerning the Mỹ Lai massacre. As a direct result of what he experienced, Thompson experienced posttraumatic stress disorder, alcoholism, divorce, and severe nightmare disorder. Despite the adversity he faced, he remained in the United States Army until November 1, 1983, then continued to make a living as a helicopter pilot in the Southeastern United States.

The page included transcribed exchanges between Thompson and Calley on March 16 1968, as Thompson verbally defied Calley repeatedly:

Immediately after the execution, Thompson discovered the irrigation ditch full of Calley’s victims. Thompson then radioed a message to accompanying gunships and Task Force Barker headquarters, “It looks to me like there’s an awful lot of unnecessary killing going on down there. Something ain’t right about this. There’s bodies everywhere. There’s a ditch full of bodies that we saw. There’s something wrong here.”: Thompson spotted movement in the irrigation ditch, indicating that there were civilians alive in it. He immediately landed to assist the victims. Lieutenant Calley approached Thompson and the two exchanged an uneasy conversation[:]

Thompson: What’s going on here, Lieutenant?

Calley: This is my business.

Thompson: What is this? Who are these people?

Calley: Just following orders.

Thompson: Orders? Whose orders?

Calley: Just following…

Thompson: But, these are human beings, unarmed civilians, sir.

Calley: Look Thompson, this is my show. I’m in charge here. It ain’t your concern.

Thompson: Yeah, great job.

Calley: You better get back in that chopper and mind your own business.

Thompson: You ain’t heard the last of this!

As Thompson was speaking to Calley, Calley’s subordinate, Sergeant David Mitchell, fired into the irrigation ditch, killing any civilians still moving. Thompson and his crew, in disbelief and shock, returned to their helicopter and began searching for civilians they could save.

Thompson died of cancer in 2006, at the age of 62.

Summary

In March 2022 (and March 2018), social media posts commemorated the anniversary of the My Lai massacre, and the role of Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson in preventing further needless slaughter of civilians. Both posts referenced above were largely accurate, but the 2022 iteration was off by four years and four days. By all accounts, Thompson acted emphatically and immediately upon witnessing the atrocities, defying Calley and later testifying against the men responsible. Thompson was later honored alongside two other soldiers (Glenn Andreotta, killed in action in April 1968, and Lawrence Colburn.) However, Thompson was ostracized in the immediate aftermath, and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorders following his intervention during the My Lai massacre.

- 'Today is the 50th anniversary of the My Lai Massacre, when US soldiers raped and murdered 500 Vietnamese civilians and burned their homes. Only one man, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, and his flight crew stopped the massacre by blocking American soldiers' | Twitter

- 'Today is the 50th anniversary of the My Lai Massacre, when US soldiers raped and murdered 500 Vietnamese civilians and burned their homes. Only one man, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, and his flight crew stopped the massacre ...' | Facebook

- My Lai Massacre | History.com

- My Lai Massacre | PBS.org

- Hugh Thompson Jr. | Wikipedia