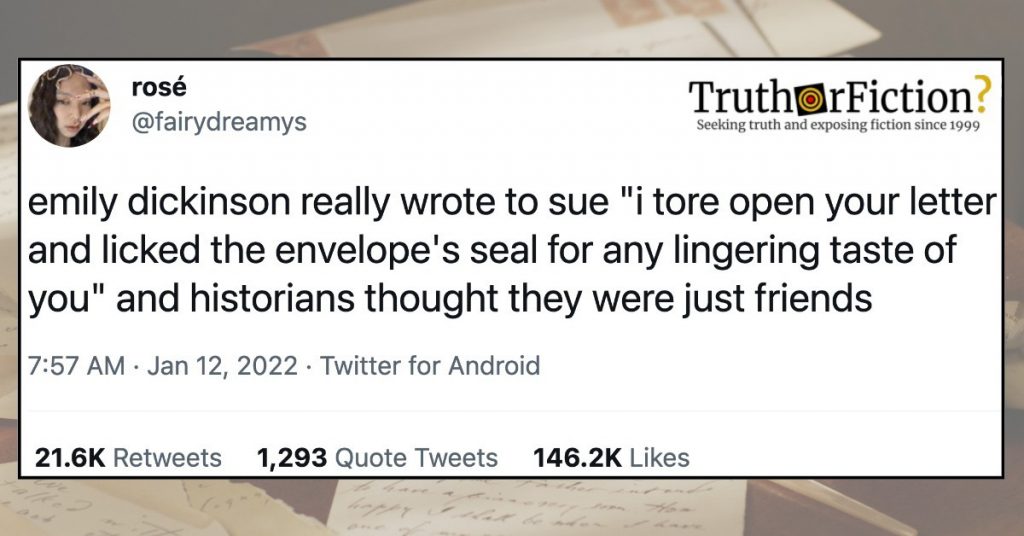

A viral January 12 2022 tweet purportedly quoting a letter by Emily Dickinson to a female friend (“I tore open your letter and licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering taste of you”) quickly spread in screenshots on Facebook and Imgur:

Broadly, the tweet was part of a larger “just gals being pals” meme, described on KnowYourMeme as a form of bi erasure:

Fact Check

Claim: "emily dickinson really wrote to sue ‘i tore open your letter and licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering taste of you’ and historians thought they were just friends"

Description: A January 12 2022 tweet maintaining that Emily Dickinson "really wrote to sue ‘i tore open your letter and licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering taste of you’ and historians thought they were just friends. The claim is in two parts; first that Dickinson wrote this specific line to Sue, and secondly how historians interpreted their relationship.

Gal Pals and Live-in Gal Pals are jokes popular in the LGBTQ community made to mock heteronormative media’s erasure of bisexuality among women.

Text of the tweet referenced author Emily Dickinson and a letter recipient identified only as “Sue”:

emily dickinson really wrote to sue “i tore open your letter and licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering taste of you” and historians thought they were just friends

It contained a claim and a sub-claim, one being that Dickinson penned the “licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering taste of you” letter. A second sub-claim was that historians remained ignorant of Dickinson’s affection for a woman named Sue, dismissing the purported writings as those of “just friends.”

Emily’s Letter to Sue: ‘I Tore Open Your Letter and Licked the Envelope’s Seal for Any Lingering Taste of You’

A search for “‘i tore open your letter’ and licked the envelope’s seal for ‘any lingering taste of you,'” partly in quotes, returned only eight results on January 14 2022 — all related to the tweet. Restricting the results to any before December 1 2021 returned only misdated content related to the January 2022 tweet.

Single-digit Google search results could hint at a fabricated quote or something novel, but searching for “I tore open your letter” and “Emily Dickinson” together returned 33 results. One of the results was a 1996 article in a biannual academic publication, The Emily Dickinson Journal.

A Spring 1996 entry, “Suing Sue: Emily Dickinson Addressing Susan Gilbert,” identified “Sue” as Susan Gilbert Dickinson. It began with the quote, and indeed framed the relationship between Dickinson and “Sue” as a “long friendship”:

I tore open your letter and licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering trace of you

Susan Gilbert Dickinson was a person of primary significance to Emily Dickinson, as testified to by the long friendship they maintained through written correspondences. Yet in Dickinson’s poems, letters, and letter-poems, Sue’s name begins to stand for an abstract idea of friendship rather than a particular friend. Her name is the answer to a riddle, a rhyme word, and a pun, as when she plays with the double meaning of “to sue” (either to petition for grace or to put on trial for a wrong committed), though it remains an identifiable individual’s name. It is the disconnecting of the name from the incarnate person, the transformation of her into a figure, which makes Dickinson self-conscious. The most telling example of this self-consciousness comes in a late letter-poem sent to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, which begins “Morning / might come / by Accident—,” and the related texts which cluster around it. I argue that this letter-poem simultaneously proclaims how much the addressee matters to the poet as an incarnate person and displays how much she has come to function as a figure in Dickinson’s imagination. The tension between the two roles the writer assigns Susan is what animates Dickinson to continue to tell her friend why she cannot see her, and why her presence, even if only imagined, means so much to her …

Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson was the subject of an entry on the website for the Emily Dickinson Museum, which referenced their “intimate correspondence”:

Susan had become close friends with Emily Dickinson in 1850. Their intimate correspondence, occasionally interrupted by periods of seeming estrangement, nevertheless lasted until the poet’s death in 1886. Susan, a writer herself, was the most familiar of all the family members with Dickinson’s poetry, having received more than 250 poems from her over the years. At least once she offered constructive criticism and advice. Susan wrote the poet’s remarkable obituary, which appeared in the Springfield Republican on May 18, 1886.

Dickinson’s letters to “Sue” were also the subject of a 2018 article on the website TheMarginalian.org (formerly Brain Pickings), “Emily Dickinson’s Electric Love Letters to Susan Gilbert”:

Four months before her twentieth birthday, Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830–May 15, 1886) met the person who became her first love and remained her greatest — an orphaned mathematician-in-training by the name of Susan Gilbert, nine days her junior. Throughout the poet’s life, Susan would be her muse, her mentor, her primary reader and editor, her fiercest lifelong attachment, her “Only Woman in the World.”

I devote more than one hundred pages of Figuring to their beautiful, heartbreaking, unclassifiable relationship that fomented some of the greatest, most original and paradigm-shifting poetry humanity has ever produced. (This essay is drawn from my book.)

[…]

A tempest of intimacy swirled over the eighteen months following Susan’s arrival into the Dickinsons’ lives. The two young women took long walks in the woods together, exchanged books, read poetry to each other, and commenced an intense, intimate correspondence that would evolve and permute but would last a life- time. “We are the only poets,” Emily told Susan, “and everyone else is prose.”

By early 1852, the poet was besotted beyond words. She beckoned to Susan on a Sunday:

Come with me this morning to the church within our hearts, where the bells are always ringing, and the preacher whose name is Love — shall intercede for us!

Although the quote was perhaps not widely noticed until it was highlighted by the viral tweet, it appeared in academic publications as early as 1996.

‘… And Historians Thought They Were Just Friends’

“Historians thought they were just friends” was a common facet of the “just gals being pals” meme — but it also raised the question of how historians viewed Dickinson’s expressions, and whether the view had changed over the years.

Tumblr users frequently posted content about Dickinson’s sexual orientation; the following post was published in May 2017: