In the early evening of March 27 2020, news that Americans would receive COVID-19 stimulus checks of $1,200 or higher was a flashpoint of discussion in the reporting of the passage of the the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, also called the CARES Act.

Initial reporting often focused on attendant “stimulus” payments purportedly marked for disbursements to Americans in varying amounts depending on their circumstances. Individual taxpayers over a certain age were said to be eligible for $1,200, and married taxpayers might receive $3,400; a clause involved individual payments of $500 per child under the age of 17:

Most adults will get $1,200, although some would get less. For every qualifying child age 16 or under, the payment will be an additional $500.

Many Americans obtained information about the stimulus payments through hastily authored “explainers,” “FAQs,” and 2020 stimulus check calculators across the web in the hours after the bill passed. And even before any legislation was voted on, the amounts of the one-time payments were flagged as insufficient to bolster the average American facing the economic fallout of widely-observed social distancing and quarantine measures for even a month.

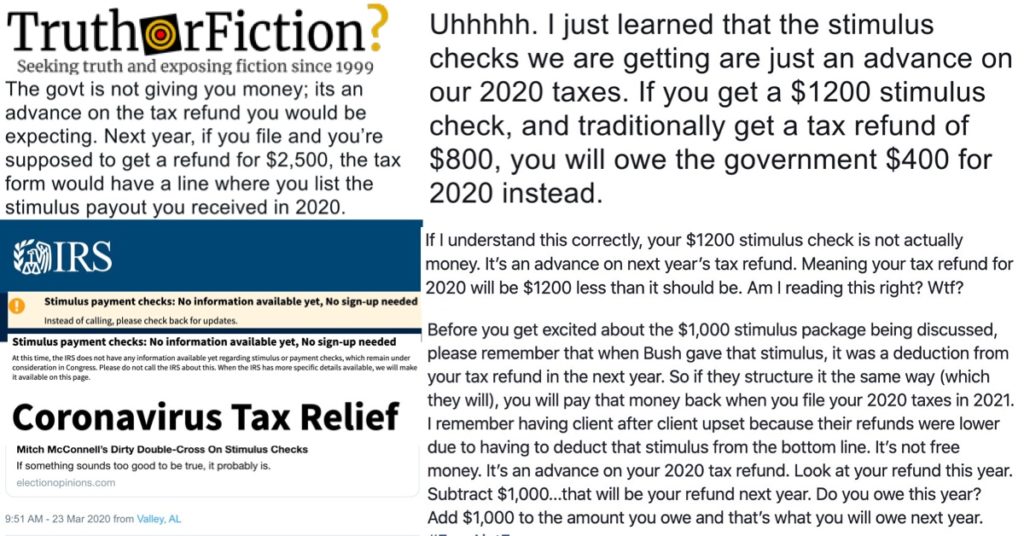

However, news about the $1,200 payments led to another broadly spreading claim — that the American government was not, as it seemed to indicate, supplying the funds itself, but instead simply advancing taxpayers a share of their own anticipated 2021 tax refund:

“Remember: The money is likely an advance. IT IS A LOAN. Functionally this is the same as the Bush Stimulus Plan of 2008 and that money, YOUR MONEY, will come out of your future tax refund. Don’t fall all over yourselves being grateful. It’s a fucking scam designed to pacify you.”

“So, all that money coming our way isn’t really anything we can spend. It’s actually an advance on a tax credit for next year and we may have to pay it back. Lovely. Another ‘give away’ that gives nothing to people who need it but bails out the big corporations yet again. I’m really tired of this shit.”

“Before you get excited about the $1,000 stimulus package being discussed, please remember that when Bush gave that stimulus, it was a deduction from your tax refund in the next year. So if they structure it the same way (which they will), you will pay that money back when you file your 2020 taxes in 2021. I remember having client after client upset because their refunds were lower due to having to deduct that stimulus from the bottom line. It’s not free money. It’s an advance on your 2020 tax refund. Look at your refund this year. Subtract $1,000…that will be your refund next year. Do you owe this year? Add $1,000 to the amount you owe and that’s what you will owe next year.”

On Twitter, similar claims followed news of the stimulus checks, which again often involved some wiggle room about whether or not tax refunds would be reduced by the amount of their stimulus credit:

Other tweets were less “if” and “likely” reliant:

If anything was certain, it was that Americans out of work and relying on a lifeline from the government didn’t know if what was described as a windfall would, in fact, place them even further behind financially when tax season rolled around in 2021.

A blog post circulating on Twitter explicitly claimed that the money was not a bonus, but instead drawn against any possible refund to taxpayers for 2020 in 2021:

The McConnell proposal calls for giving Americans that money as an advance on a future tax refund.

In other words, this is not a giveaway, or socialism, or some act of generosity.

The government is not giving you money; it is giving you an advance on the tax refund you would be expecting in 2021.

For example, say you’re a married couple with no children and you receive a check for $2,400 now. Next year, if you’ do your taxes and you’re supposed to get a refund for $2,500, the tax form would have a line where you list the stimulus payout you received in 2020. The IRS would deduct that $2,400 and give you the net difference of $100 as your 2020 refund check.

This is also how the process worked as part of the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, although the advances then were $300 for individuals or $600 for couples.

The government could choose to issue the payments as a gift, but even gifts come with strings attached. The checks would be considered taxable income and recipients would owe taxes when filing their 2020 tax returns. For a married couple with two children (receiving a $3,400 gift), would incur a tax hit of nearly $750 if their household income was $80,000.

On March 25 2020, the same blogger reiterated that the money would be drawn against refunds paid out in 2021:

The proposed legislation would issue payouts of $1,200 to individuals, $2,400 to married couples and $500 per dependent child. The Republicans conceded to Democratic demands that the payments not be income-based and not phase-out for low or higher earners … The CARES Act calls for giving Americans money as an advance on a future tax refund.

In other words, this is not a free-money giveaway, or socialism run wild, or some act of generosity on the part of those controlling the purse in Washington.

The government is not giving you money, no matter how badly you are hurting financially.

The government is giving you an advance on the tax refund you would be expecting in 2021.

For example, say you’re a married couple with one child, and you receive a check for $2,900 now ($1,200 each and $500 for child).

Next year, when it comes time to do your taxes, and you’re supposed to get a refund for $3,500, the tax form would have a line where you list the stimulus payout you received in 2020.

The $2,900 advance would be deducted from your expected refund, leaving a net refund of $600.

This is the way the payments in the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 were also handled … Americans will get checks now (or, electronic deposits) and come next spring will get a gut-punch when they do their taxes and realize most are not getting a refund in 2021…because they already got it in April of 2020.

The precise nature (and liability) of the coronavirus stimulus as an “advance” was a matter of particular concern for a contingent of Americans who rely on their annual tax refund to make ends meet for the rest of the year. In 2015, The Atlantic reported that “a majority of Americans [eligible for refunds] plan to use their refunds to pay off debt or cover basic necessities” — speaking to several taxpayers whose refunds were already earmarked for medical bills or housing by the time they arrived:

Adults over the age of 40 without a college degree were the most likely group to use their refund to pay for necessities. Barbara Thomas, 58 from Irrigon, Ore., already spent her tax refund on medical bills from a recent surgery to remove cancerous melanoma. Thomas works seasonally in the fishing industry and over the winter, she and her husband have tried to stretch his retirement income to cover both their regular expenses and her doctor’s appointments. Anything extra that comes their way–whether her refund or fuel savings–makes all the difference.

“It just makes it a lot easier to make ends meet,” Thomas said. “Living on social security is tough.”

In early March 2020, Marketplace reported that most of the taxpayers getting refunds indicated an inability to survive financially without that money — a pattern of relief disrupted by changes to the tax code in 2017:

Every year, the tax refund was spent before it arrived. Chris MarkerMorse and his wife, both teachers in high-need public schools in California, knew they’d use it to pay off credit card debt they racked up buying supplies for their classrooms, their students, their schools.

“We spent quite a lot of money on that each year,” he said. “We’d put it on a credit card, get points, and then we’d use our tax refund to pay down that credit card.”

They relied on it. A lot of people do. A majority of Americans, in fact, who get refunds. Sixty-eight percent of those who expect a refund in any given year say it’s important to their financial well-being, according to a survey out Wednesday from CreditCards.com. A third say it’s very important.

“That’s not surprising,” said Mark Mazur, the director of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “If you think that the average income tax refund approaches $3,000, that could be one month’s worth of income for a moderate-income household. So, not surprising that it’s a significant fraction of their cash flow for the year.”

The refund landscape has changed for low- and middle-income families, though, since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 went into effect. Many Americans saw their tax refunds drop last year, some significantly, whether because the withholding tables changed and they got more in their paycheck throughout the year, or in some cases because their taxes went up. In both instances, there were a lot of people who got hit hard.

One Forbes contributor blogged some questions and answers, assuring readers that taxpayers “won’t lose out” on their anticipated 2020 tax year refund in 2021:

A refundable credit means that you can take advantage of the credit even if you do not owe any tax. Unlike with a nonrefundable credit, if you don’t have any tax liability, the “extra” credit is not lost but is instead refunded to you.

In this case, the stimulus check acts like a refund that you get in advance based on your 2020 income. That’s confusing because you don’t know how much you’re going to earn in 2020, but it’s why the IRS is using earlier returns. But this advance payment on the credit does not affect your “normal” tax refund for 2020: you won’t lose out on your expected tax refund for 2020 with the check.

A different contributor on Forbes’ platform also attempted to determine the source of the money, making what looked like a conflicting claim — that taxpayers who received “too much” coronavirus stimulus money would be on the hook in 2021:

The stimulus is an advance of a refundable tax credit on your 2020 taxes.

In other words, the bill created a refundable tax credit and the IRS is paying out the amount of that tax credit to eligible taxpayer now. Since the IRS does not have your 2020 tax year information, it will use a previous year’s information to calculate the amount.

This is a tax credit so it is not considered taxable income for 2020.

If the IRS gives you too much of a stimulus check, you could be asked to pay back the difference but not until you file your return on April 15, 2021. You will not be assessed interest on the over-payment amount. If the IRS pays you too little, you’ll get the difference added to your tax refund next year.

An undated blog post on the Tax Act blog described also the payments as an advance:

Technically, the [coronavirus stimulus] money is an advance of a refundable credit on your 2020 return. A refundable credit is a tax benefit you can take advantage of even if you do not owe any tax. If you qualify to claim it, any money that isn’t needed to pay down your tax liability is refunded to you. Basically, the stimulus payments are advance refunds based on your 2020 income.

If you’re confused, that’s understandable; it is confusing. Obviously, no one can be sure how much you’re going to earn in 2020. That’s why the IRS is basing how much you’re due off prior year tax returns. When you file your 2020 return, the IRS will compare what you received this year for the credit with what you qualify for based on your 2020 income.

If you should have received a payment and didn’t, or if you should have received more than you did, you will receive additional money. If the numbers on your 2020 tax return suggest you got more than you should have, you won’t have to pay it back. Considering most people’s incomes don’t flucutate too much from year to year, most everyone should receive the right amount the first go-around.

In an above-linked explainer, the New York Times reported that the coronavirus-related stimulus included a $500 bonus for “every qualifying child age 16 or under” in a qualifying taxpayer’s family. That particular detail stood out — the previous month, in February 2020, USA Today‘s reporting on the Earned Income Tax Credit addressed qualifying children in a given tax year.

That article (“Millions of Americans are missing out on Earned Income Tax Credit”) included tax code information which was possibly pertinent in determining where the “advance on a tax refund” aspect came in:

How do I know whether my child would qualify?

Among other requirements, the child must be under age 19 at the end of the year and younger than you or your spouse, if you file a joint return.

Or the child can be a full-time student in at least five months of the year and under age 24 at the end of the year and younger than you or your spouse, if you file a joint return.

Per the IRS and regarding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), any qualifying child was required to be under the age of 19 at the end of the tax year — which in this case is 2019.

The CARES Act and the coronavirus stimulus checks were intended for distribution in April or May 2020 — and it requires qualifying children to be under the age of 17. A dependent born on July 15 2003 would be 16 at the end of 2019, thus qualifying for the EITC in that tax year. But that same child would be 18 in 2021, not qualifying for the EITC in the 2020 tax year or on 2021’s return.It seems possible that the CARES act shaved two years from the age of qualifying youths because parents who received the EITC in 2019 and saw it reflected in any 2020 refund on taxes would not, in fact, see the same tax credit in a 2021 refund on 2020’s taxes. In other words, revising the eligible age of dependents downward hinted at the potential relevance of 2020 tax year filings in 2021.

A March 28 2020 article on business advice and news site Kiplinger.com (“Will You Get a Bigger Stimulus Check by Waiting to File Your Tax Return?” via Nasdaq.com) noted that taxpayers who hadn’t filed taxes in 2020 for 2019 could conceivably delay filing so that the IRS would use their 2018 return instead — possibly providing them a higher stimulus check based on those earlier earnings. But uncertainty about overpayments creating tax debt pointed to possibly yet-undecided functions of the payment:

Back in 2008, when we had a similar stimulus check program, there was no mechanism for paying back any “extra” stimulus check money. The IRS hasn’t said yet if they’ll repeat that approach this time around, but we’re keeping an eye out for guidance addressing the situation. Stay tuned!

In reporting on the nature of the stimulus payments, all roads led back to IRS guidance issued to taxpayers on EITC, refunds, dependents, and other tax liabilities or offsets. The IRS maintained a “Coronavirus Tax Relief” page, which was absolutely no clearer than any speculative articles or social media posts.

This is what it looked like as of March 30 2020:

A large yellow “!” message at the top of the page implored confused taxpayers not to call to ask the IRS about the coronavirus stimulus checks:

Stimulus payment checks: No information available yet, No sign-up needed Instead of calling, please check back for updates.

Three days after the bill’s March 27 2020 passage, a subsequent portion read:

Stimulus payment checks: No information available yet, No sign-up needed

At this time, the IRS does not have any information available yet regarding stimulus or payment checks, which remain under consideration in Congress. Please do not call the IRS about this. When the IRS has more specific details available, we will make it available on this page.

On March 29 2020, the verified Twitter account @IRSNews tweeted the same link, but the IRS has still not answered any questions about whether the stimulus checks were coming out of 2021 tax refunds:

On the 26th and 27th, the IRS again urged taxpayers not to call to ask about their coronavirus stimulus checks, and offered no guidance about whether the payments would be deducted from any anticipated 2020 refund in 2021. The account also tagged media personalities, encouraging them to spread the word about the IRS not having any information about the payments:

One of the two Forbes contributor advised readers with additional questions to visit the March 25 2020 Congressional Record [PDF], a 147-page long document with no obvious additional information about the source of the coronavirus stimulus checks. It included significant transcribed bickering between elected officials, but very little in terms of meaningful information about whether the $1,200 was coming from Americans’ 2020 tax year refunds or somewhere else.

On pages 63 and 64 of that document, a section addressed “recovery rebates for individuals,” which referenced US Code. It indicated the payments as proposed on March 25 2020 were “a credit against the tax imposed” under federal tax code:

SEC. 6428. 2020 RECOVERY REBATES FOR INDIVIDUALS.

“(a) IN GENERAL.—In the case of an eligible individual, there shall be allowed as a credit against the tax imposed by subtitle A for the first taxable year beginning in 2020 an

amount equal to the sum of— [$1,200, $2,400, and $500 for qualifying dependents]“(e) COORDINATION WITH ADVANCE REFUNDS OF CREDIT.—

“(1) IN GENERAL.—The amount of credit which would (but for this paragraph) be allowable under this section shall be reduced (but not below zero) by the aggregate refunds and credits made or allowed to the taxpayer under subsection (f). Any failure to so reduce the credit shall be treated as arising out of a mathematical or clerical error and assessed according to section 6213(b)(1).[…]

“(1) IN GENERAL.—Subject to paragraph (5), each individual who was an eligible individual for such individual’s first taxable year beginning in 2019 shall be treated as having made a payment against the tax imposed by chapter 1 for such taxable year in an amount equal to the advance refund amount for such taxable year.

“(2) ADVANCE REFUND AMOUNT.—For purposes of paragraph (1), the advance refund amount is the amount that would have been allowed as a credit under this section for such taxable year if this section (other than subsection (e) and this subsection) had applied to such taxable year.

It appeared the referenced tax code was U.S. Code 26, Subtitle A: Income Taxes — essentially, the portion of the code establishing and structuring the payment of income tax — but the excerpted portion didn’t really clarify what effect the credit might have on tax returns in 2021 (for income tax paid in 2020.)

GovTrack.us provided the full text of H.R. 748: Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (or the CARES ACT) as of March 28 2020. Under “TITLE II—Assistance for American Workers, Families, and Businesses,” “Subtitle B—Rebates and other individual provisions,” was “Sec. 2201. 2020 recovery rebates for individuals,” which very closely matched the portion excerpted from the March 25 2020 Congressional Record above.

Section (F), subsections (1) and (2) held:

(f)Advance refunds and credits

(1)In general

Subject to paragraph (5), each individual who was an eligible individual for such individual’s first taxable year beginning in 2019 shall be treated as having made a payment against the tax imposed by chapter 1 for such taxable year in an amount equal to the advance refund amount for such taxable year.(2)Advance refund amount

For purposes of paragraph (1), the advance refund amount is the amount that would have been allowed as a credit under this section for such taxable year if this section (other than subsection (e) and this subsection) had applied to such taxable year.

Section (F), subsection (4) made reference to interest on overpayment, which suggested that the amount of the credits would be in some way relevant to 2020 tax returns filed in 2021:

No interest shall be allowed on any overpayment attributable to this section.

Unfortunately, language of the bill was not very clear on whether coronavirus stimulus checks distributed via the IRS would be deducted from anticipated 2021 refunds for the 2020 tax year. Explainers and FAQs focused primarily on who would receive which amount, but were light on any reference to what effects, if any, the stimulus payments might have on future tax refunds. In the bill, text says “each individual who was an eligible individual for such individual’s first taxable year beginning in 2019 shall be treated as having made a payment against the tax imposed by chapter 1 for such taxable year in an amount equal to the advance refund amount for such taxable year, and they were described as an “advance refund.”

Although questions were supposed to be directed to the Internal Revenue Service, the IRS repeatedly said across channels and its site that it “does not have any information available yet regarding stimulus or payment checks, which remain under consideration in Congress.” And while some reporting said no “overpayment” would result in future tax liability, other assessments indicated incorrect payments could result in April 2021 tax liability — albeit, maybe, without interest.

Update, April 15 2020: For additional information on the current status of coronavirus stimulus payments, or if your deposit has not arrived, please visit:

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act

- Trump Signs $2 Trillion Coronavirus Stimulus Bill After Swift Passage by House

- F.A.Q. on Stimulus Checks, Unemployment and the Coronavirus Plan

- Democrats balk at $1,200 rebate checks in stimulus plan

- $2 Trillion Coronavirus Stimulus Bill Is Signed Into Law

- Some Americans Depend on Their Tax Refunds to Survive

- Millions of Americans are missing out on Earned Income Tax Credit

- How To Maximize Your Coronavirus Stimulus Check

- All You Wanted To Know About Those Tax Stimulus Checks But Were Afraid To Ask

- Will You Get a Bigger Stimulus Check by Waiting to File Your Tax Return?

- Coronavirus Tax Relief

- Congressional Record PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116th CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

- US Code 26 Subtitle A—Income Taxes

- Coronavirus Stimulus Payments: When Will They Be Sent and Who Is Eligible?

- Everything You Need to Know About the Stimulus Payments

- H.R. 748: Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act

- Mitch McConnell’s Dirty Double-Cross On Stimulus Checks

- Mitch McConnell, Senate Complete Stimulus Check Swindle