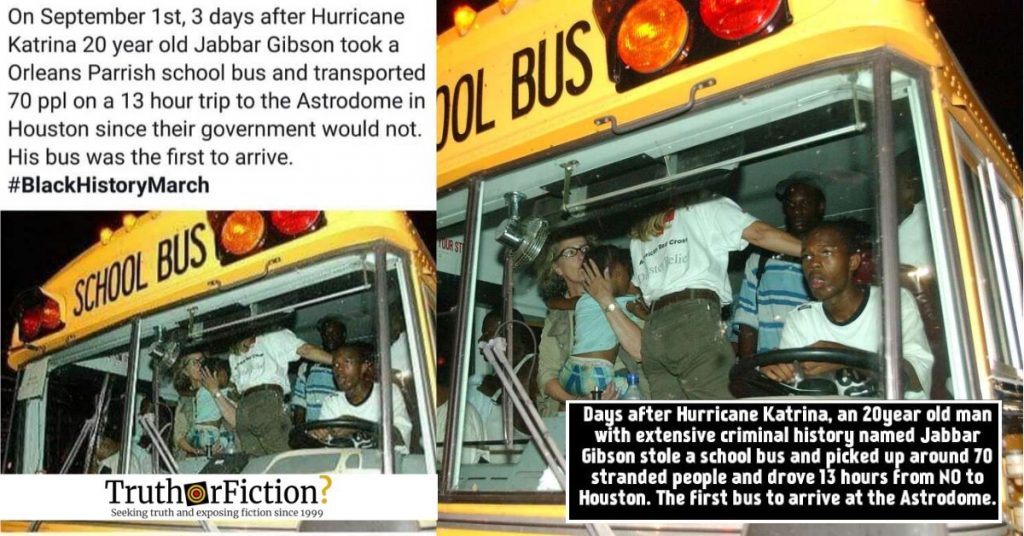

On February 1 2022, the following meme was shared to Imgur, describing the actions of a man identified as “Jabbar Gibson” in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina:

That image was clearly a screenshot, and it appeared to show a cropped Facebook post. A search of Facebook returned another post featuring the screenshot by “Allies Academy” in November 2021.

Fact Check

Claim: "On September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 ppl on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive."

Description: On September 1st, three days after Hurricane Katrina, 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 people on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston, since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive.

Above a photograph of a young Black man at the wheel of a crowded school bus at night, text read:

On September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina[,] 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took [an] Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 ppl on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive. #BlackHistoryMarch

Identical text (including the “Jabbar Gibson” spelling) appeared on Twitter in September 2019. That image was also included, along with two others:

Still more versions of the meme were hosted on Tumblr’s domain. Searches returned an older version of the story shared to Reddit’s r/todayilearned in 2013:

Hurricane Katrina, a devastating and deadly storm primarily remembered for the intense damage it inflicted on New Orleans, occurred in late August 2005. That Reddit post linked to an archived Chron.com article, first published on September 1 2005 — “Bus comandeered by renegade refugees first to arrive here.”

Gibson was identified as the driver of the bus, described as the first to reach Houston. The first few paragraphs of the article described chaos and horror of the storm were a harrowing read:

The first busload of New Orleans refugees to reach the Reliant Astrodome overnight [on September 1 2005] was a group of people who commandeered a school bus in the city ravaged by Hurricane Katrina and drove to Houston looking for shelter.

Jabbar Gibson, 20, said police in New Orleans told him and others to take the school bus and try to get out of the flooded city.

Gibson drove the bus from the flooded Crescent City, picking up stranded people, some of them infants, along the way. Some of those on board had been in the Superdome, among those who were supposed to be evacuated to Houston on more than 400 buses Wednesday and today. They couldn’t wait.

The group of mostly teenagers and young adults pooled what little money they had to buy diapers for the babies and fuel for the bus.

It got worse from there, and Gibson explained that the fleeing New Orleanians were denied the shelter that they had been promised by officials:

After arriving at the Astrodome at about 10:30 p.m. [the night before], however, they initially were refused entry by Reliant officials who said the aging landmark was reserved for the 23,000 people being evacuated from the Louisiana Superdome.

“Now, we don’t have nowhere to go,” Gibson said. “We heard the Astrodome was open for people from New Orleans. We ain’t ate right, we ain’t slept right. They don’t want to give us no help. They don’t want to let us in.”

[…]

They looked as bedraggled as their grueling ride would suggest: 13 hours on the commandeered bus driven by a 20-year-old man. Watching bodies float by as they tried to escape the drowning city. Picking up people along the way. Three stops for fuel. Chugging into Reliant Park, only to be told initially that they could not spend the night.

At the time of publication, evacuation remained underway. and numerous other incidents related to Katrina dominated the news. But that early report of Gibson’s attempt to save fellow residents was part of the developing story.

One year to the day that the Chron.com article appeared, The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley published a piece titled “The Banality of Heroism.” Its theorized:

… because evil is so fascinating, we have been obsessed with focusing upon and analyzing evildoers. Perhaps because of the tragic experiences of the Second World War, we have neglected to consider the flip side of the banality of evil: Is it also possible that heroic acts are something that anyone can perform, given the right mind-set and conditions? Could there also be a “banality of heroism”?

Gibson, referenced as “Jabar Gibson,” was mentioned shortly thereafter — and the article again noted that Gibson’s bus arrived more quickly than “government sanctioned evacuation efforts”:

The banality of heroism concept suggests that we are all potential heroes waiting for a moment in life to perform a heroic deed. The decision to act heroically is a choice that many of us will be called upon to make at some point in time. By conceiving of heroism as a universal attribute of human nature, not as a rare feature of the few “heroic elect,” heroism becomes something that seems in the range of possibilities for every person, perhaps inspiring more of us to answer that call.

Even people who have led less than exemplary lives can be heroic in a particular moment. For example, during Hurricane Katrina, a young man named Jabar Gibson, who had a history of felony arrests, did something many people in Louisiana considered heroic: He commandeered a bus, loaded it with residents of his poor New Orleans neighborhood, and drove them to safety in Houston. Gibson’s “renegade bus” arrived at a relief site in Houston before any government sanctioned evacuation efforts.

In April 2006, NBC News reported that Gibson had been arrested in November 2005, shortly after his return to New Orleans from Houston:

Gibson got a movie offer and coast-to-coast media attention after he stole a yellow Orleans Parish school bus and drove 60 people from New Orleans to the Astrodome in Houston. He was not charged for swiping the bus.

Gibson was arrested Nov. 25 [2005] shortly after he returned to the city from a temporary home in a Houston hotel. He was free on bond at the time of his second arrest, authorities said.

In 2010, the Department of Justice issued a press release indicating that Gibson had been sentenced to 15 years in prison. On July 29 2015, BuzzFeedNews published a long-form article about Gibson’s actions during Hurricane Katrina — “How A Small-time Drug Dealer Rescued Dozens During Katrina.”

That piece provided a bit more detail about the events preceding Gibson’s evacuation of himself and other residents, detailing the increasingly dire conditions in New Orleans:

After two days without power, food, or even a merciful Gulf Coast breeze, and no assurances that anyone would come save them, Gibson and a small group of friends started thinking of ways to escape. They hit the streets with a piece of hose pipe and a plastic jug to siphon gas. Within hours, they had found gas, but the truck they wanted to use wasn’t reliable enough or big enough for an escape.

“We were desperate,” said Kerry Lavinette, a longtime resident of Fischer. “It was either that or we were going to drown.”

Soon they spotted a school bus rumbling down L.B. Landry Avenue, a major street that runs from the Mississippi River Bridge through the Fischer Projects and into Algiers, a neighborhood sometimes called the 15th Ward. Gibson and his friends flagged down the driver to ask where he got the bus. “Algiers Point,” he told them.

There they found about a dozen yellow school buses parked in a barn. Inside an unlocked office, Gibson and his friends found keys hanging on a door. They checked the numbers on the keys and matched them to the buses. It took about a half hour to find a bus that would start. Orleans Parish school bus No. 0232 had been left behind with a full tank of gas.

“I learned how to [drive the bus] right then and there,” Gibson said, a smile creasing his face. “I was driving all right for the first time.”

From there, Gibson and his friends went off in search of others stranded and in need of immediate assistance. The piece continued, reporting that as of 2015, Gibson was incarcerated, a depressing coda to Gibson’s heroic act:

While the memories of their misery are vivid, so are their memories of the lanky young man who saved them: Jabbar Gibson.

These days, he’s better known as Inmate No. 29770-034 at the Federal Correctional Institution in Pollock, Louisiana. Gibson has been there since 2010 for gun and drug possession, locked away from his people and the Fischer, which has since been razed and rebuilt into a sprawling development of small, pastel-colored homes built on the same sun-baked dirt of the West Bank of the Mississippi.

[…]

Gibson relished the idea that anyone on the outside still remembers him as something more than a low-level drug pusher from New Orleans. “Being called a hero was cool,” Gibson told BuzzFeed News during a May [2015] interview at the prison. “I’ve missed out on a lot being up in here.”

Later in the article, BuzzFeed again detailed elements of the escape, noting that the bus and its occupants worried that police would halt the effort. It was not an unfounded concern:

As things grew more desperate, Gibson was willing to take a risk. To escape, they’d have to think big. He’d seen that bus coming down Landry Avenue. He knew the bus lot wasn’t too far away. He’d stolen a vehicle before. Why not now, with their lives on the line?

“He was like, ‘I’m about to go get a bus and I’m coming back,’” Tranice Gibson said.

There wasn’t much time to waste — they figured they’d have to beat the rising waters or the police, who might try to stop residents from using stolen buses to escape — to get to safety. Word had already filtered through the gossipy webs of Fischer, and people were lining up to get onto the buses, their meager belongings in tow.

About 60 people had climbed aboard Gibson’s bus when the police arrived at the scene. The officers made everyone get off the bus. Gibson handed over the keys and fled the scene. Only his mother [Bernice] remained.

Police eventually relented, permitting the evacuees to escape with their lives. Participants recalled a risky escape route, but one they were grateful to have:

Nonetheless, Bernice Gibson said she managed to convince the officers that giving Jabbar the keys and letting him take control of the bus was necessary to evacuate people who were in dire need of help.

“It ain’t the police who was helping us” get out of there, she said. The officers relented and handed the keys back to Gibson when he returned.

“Get on the bus,” Gibson recalled one of the officers telling him, “and don’t stop.”

[…]

People streamed out of the Fischer again, yelling and running in all directions. They crowded onto the bus again. Gibson had no fewer than a dozen family members and nearly as many friends coming along for the ride. Three to four people were crammed onto each seat. Some stood in the middle aisle, while those lucky enough to sit had someone on their laps.

“We were bunched up all kinds of ways,” [Roger Robinson, a friend of Gibson’s] said. But they were thrilled, relieved, almost delirious. “We all were clowning,” recalled Byronisha Crockett, still a Fischer resident today.

Few people seemed concerned about Gibson’s ability to navigate a lengthy road trip in a wobbly school bus, which, as it turned out later, had been in need of serious repairs, according to the Times-Picayune. They had little choice but to place their fates, if not their very lives, in the hands of this drug-dealing 10th-grade dropout.

Except his mother. “I couldn’t convince her to come,” Gibson said, the resignation in his voice even today. “She didn’t trust me.”

“Jabbar didn’t know how to drive no bus,” she said.

Another detail in the article and absent from more concise meme versions of the story involved what happened while the bus made its way from New Orleans to Houston. Gibson narrowly evaded another police roadblock, and passengers said he spent about $1,200 of his own money on supplies like diapers.

Despite the slow pace and stops to pick stragglers up, Gibson’s bus was described as the first convoy of people fleeing New Orleans to arrive in Houston ahead of FEMA evacuees:

There was a lot of need for such a tight space, and Gibson’s largesse continued as they made it down the road. He bought gas, snacks, and even diapers.

Some of this was practical: Gibson didn’t want people to rush off the bus and draw attention to law enforcement in the remote towns that dotted Highway 90. Some of this was borne out of necessity: He was one of the few people who had money. He figures that he spent about $1,200 during the trip … Gibson and his bus had beat a caravan of other buses — those being run by FEMA — to the Astrodome by several hours.

BuzzFeed went into detail about Gibson’s life in the immediate aftermath of the feel-good story, including missed opportunities and broken promises:

While Gibson was in prison, he claims he missed out on a chance to appear in Spike Lee’s HBO documentary about Katrina, When the Levees Broke. (Lee’s production company did not respond to a request for comment.) All those promises of homes and money the Gibsons claim Oprah made to them never materialized. (A spokesperson for Winfrey said, “Oprah Winfrey spoke with numerous individuals during her 2005 visit to the Houston Astrodome and through the Angel Network supported organizations which further aided various people and communities. We cannot verify that any outreach was made to this specific individual.”)

[…]

When media outlets covered his legal troubles [in 2010], they didn’t even make reference to his heroic exploits five years earlier during Katrina. He was just another repeat drug dealer busted by the cops.

At the end of the article, the outlet noted that as of 2015, Gibson was scheduled for imminent early release. We were unable to find any news mention of Gibson after the 2015 BuzzFeedNews profile:

Gibson will be released 10 years earlier than expected, a bit of fortune that saved him from the daily despair of lockup. He will be sent to a federal halfway house in Baton Rouge on July 31 [2015], and will be officially released in January [2016].

In February 2022, an Imgur user shared a meme claiming that on “September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina[,] 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 [people] on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not,” and Gibson’s “bus was the first to arrive.” The claims were accurately reported, and verified by secondary sources in articles published during and after Katrina in 2005. Other heroic elements of the story (such as Gibson picking up additional passengers and paying for necessities) were not in the meme. Jabbar Gibson was slated for early release from prison in 2015, and we were unable to locate any further information about him.

- "On September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 ppl on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive." | Imgur

- "On September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 ppl on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive." | Allies Academy/Facebook

- "On September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 ppl on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive." | Twitter

- "On September 1st, 3 days after Hurricane Katrina 20 year old Jabbar Gibson took a Orleans Parrish school bus and transported 70 ppl on a 13 hour trip to the Astrodome in Houston since their government would not. His bus was the first to arrive." | Tumblr

- TIL days after Hurricane Katrina, an 20year old man with extensive criminal history named Jabbar Gibson stole a school bus and picked up around 70 stranded people and drove 13 hours from NO to Houston. The first bus to arrive at the Astrodome. | Reddit

- Hurricane Katrina | Wikipedia

- Bus comandeered by renegade refugees first to arrive here

- The Banality of Heroism

- "I've never forgotten this reporting by @byjoelanderson about an incarcerated Black man, Jabbar Gibson, who when he was 20 stole a school bus and drove 60 people to safety in Houston after Katrina" | Twitter

- Man hailed as hero after Katrina is indicted

- NEW ORLEANS MAN SENTENCED TO 15 YEARS IN FEDERAL PRISON FOR GUN AND DRUG VIOLATIONS

- How A Small-time Drug Dealer Rescued Dozens During Katrina