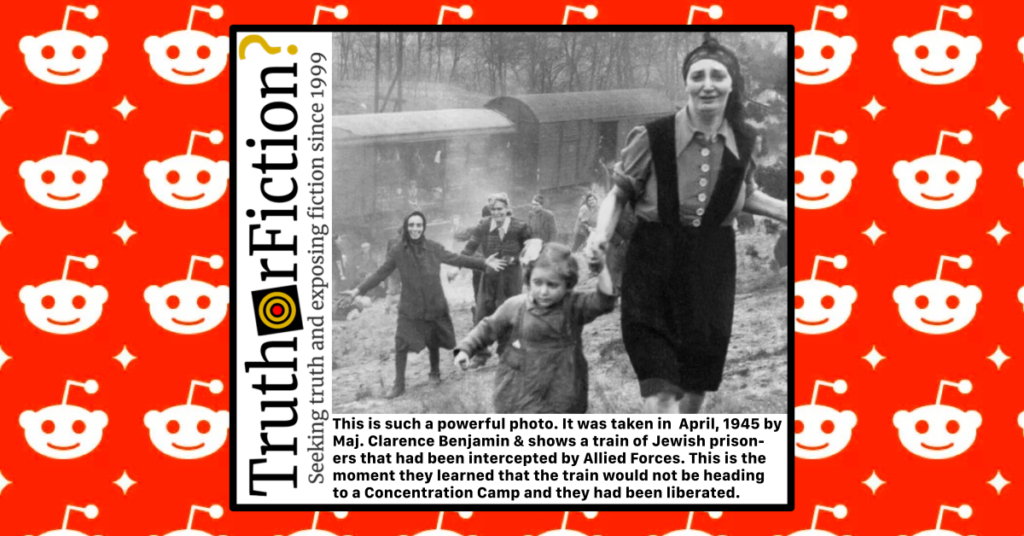

On October 22 2019 a Reddit user shared the following image to r/pics, purportedly depicting a moment during World War II when Jewish prisoners learned they had been liberated from a train traveling to a death camp:

The post in its entirety appeared in its title:

This is such a powerful photo. It was taken in April, 1945, by Major Clarence Benjamin and shows a train of Jewish prisoners that had been intercepted by Allied Forces. This is the moment they learned that the train would not be heading to a Concentration Camp and they had been liberated.

No other information accompanied the image, and comments displayed at the top didn’t link to any further information about the events it reportedly showed. A highly-upvoted comment at the beginning of the thread lamented:

Fast forward to today and we have ***** in the streets supporting Nazis and waving their flags. Humans can be such dicks.

The same image appeared on Reddit previously in a post to r/OldSchoolCool in 2016, r/HistoryPorn in 2017, and r/Europe in 2018. A title for the latter post provided a different descriptive title:

Jewish prisoners of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany, on a transport to Theresienstadt north of Prague, moments after they were liberated by the US forces on April 1945.

A Quora commenter also included the image in a 2012 answer to the question “What are the best photographs in history?” But most iterations of the image on social media did not include the coda and history for the events of the photograph itself, and developments more than half a century after it was taken.

In April 2008, author Matthew Rozell published an initial post about the image and ongoing research into its backstory. At some point, Rozell updated the post to report:

NOTE: In 2001 my students and I began to post interviews that we had conducted with World War II veterans at our school website, [link] Two of our veterans had described this incident, and one of them had taken photographs of it. Four years went by, and we heard from a grandmother in a far away country who had been a seven year old girl aboard this train. Then more survivors began to contact us, and today we are aware of over 200 survivors who have now made contact with each other and their liberators through the efforts of this school project.

We have [since] organized several reunions for [the survivors and their liberators].

Indicating that the image was captured at the very end of World War II — “as American and British forces pushed into Germany from the west and the Soviet Red Army closed in from the east” — Rozell described the effort’s initial findings:

On the morning of Friday, April 13th, 1945, the US 9th Army was fighting its way eastward in the final drive through central Germany toward the Elbe River. A small task force was formed to investigate a train that had been hastily abandoned by German soldiers near the town of Magdeburg, Germany … By the afternoon of the 13th, one tank alone was responsible for safeguarding 2500 refugees. A small guard of emaciated Finnish soldiers who were also liberated that day set up the perimeter guard. The American tank commander had a small Kodak camera. He took several photographs that day of the newly freed men, women and children and spent some time talking to them through one of the survivors who spoke English.

A video about Rozell, his students, and their efforts to uncover more information about the image was published by ABC News to YouTube in September 2009. During that month, the network also published an article detailing the efforts of Rozell and students to locate surviving people present when the photograph was taken.

According to ABC, the efforts began in 2001, with a website eventually accessed by surviving liberators and former prisoners. Rozell and his students began hearing from both, and subsequently arranged a reunion at Hudson Falls High School in Hudson Falls, New York:

In 2001, high school history teacher Matt Rozell began an oral history project. He and his students interviewed family members in the small town of Hudson Falls, N.Y., to capture fading stories of World War II. The students ended up unearthing a forgotten chapter in history.

Near the very end of World War II, on April 13, 1945, the American 30th Infantry Division was pushing its way into central Germany. They found a train carrying nearly 2,500 emaciated Jewish prisoners — many of whom were children. The prisoners were traveling from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp to another camp — a place where certain death awaited … The American soldiers rescued and fed the prisoners, evacuated them to safety and then moved on to other missions they faced in the war.

“I searched for 44 years looking for anything that mentioned a memory of that train. It didn’t exist!” said Stephen Barry, a survivor from the train.

When Rozell’s class put their interviews with veterans up on a Web site along with photographs taken by the American soldiers, Holocaust survivors from all around the world began to notice.

“We heard from a woman in Australia who had been a 7-year-old girl on the train. It hit me like a steamroller,” said Rozell.

“It was amazing when I looked at one of the pictures and I discovered myself,” Barry said. “How many people have a picture of the moment of liberation forever?”

In September 2016, Rozell published a book titled “A Train Near Magdeburg: A Teacher’s Journey into the Holocaust, and the reuniting of the survivors and liberators, 70 years on” about both the image as well as the outcome of his class’ research.

Haaretz profiled the book and its backstory in August 2016, including firsthand accounts from surviving people liberated from the train:

According to [survivor Alisa] Vitis-Shomron, “People burst out of the carriages. Suddenly someone shouted: ‘The Americans are coming!’ To our great surprise, a tank came slowly down the hill opposite, followed by another one. I ran toward the tank, laughing hysterically. It stopped. I embraced the wheels, kissed the iron plates. We had won the war.”

Another woman on the train, Hilde Huppert, then in her mid-30s, recalled in her book “Hand in Hand with Tommy” (English translation: Yael Chaver and Reuven Morgan), that a jeep approached, “manned by four G.I.s with steel helmets coated in dust. They pulled up and approached us warily: a motley crowd of women and children together with a couple of men here and there, all clad in rags and tatters. We must have been a pitiful sight. ‘Who are you?’ they demanded. ‘Hello friends!’ we shouted back in a chorus [in English]. ‘We love you! We are Jews!’ They slipped off their helmets and mopped their brows. One of them pointed to the Star of David he wore on a chain around his neck. ‘So am I.’”

Dr. Mordechai Weisskopf, a retired physician who lives in Rehovot, was a boy of 14 on the train. “The train stopped, the Germans fled and we were there without a guard, in the midst of the front, with artillery fire in the background,” he told me. “The joy that seized us at the sight of the American tank is indescribable. Suddenly, from, nonhuman slaves, we were transformed into free people. It was very thrilling, unforgettable. We saw American soldiers, and one of them shouted in Yiddish, his eyes flowing with tears, ‘I am a Jew, too.’ There was an outburst of joy that is hard to describe.”

Haaretz indicated that the image “for decades had lain, forgotten, in a shoebox in a San Diego, California, home,” until Rozell interviewed 80-year-old Carrol Walsh. Walsh relayed the story of the train’s liberation to Rozell:

One of the first U.S. soldiers to see the Jewish prisoners on the train was Capt. Carrol Walsh, the veteran who later put history teacher Rozell onto the story. Walsh also told Rozell how to get in touch with George Gross, who went on to teach English literature at the University of San Diego. From Gross he received several rare photographs documenting the moments of liberation. One of them was the now-iconic image of the woman and child.

As it turned out, that photo was taken by another soldier, Maj. Clarence Benjamin, who was on his way to conquer the city of Magdeburg. Encountering the train, he considered it his moral and humane duty to rescue the prisoners from the Nazis. As such, he captured on film the first instant of the liberation. When Rozell first perused the photographs, he realized he had come upon a treasure of incalculable worth. “A historic miracle,” he said about the fact that the soldiers had reached the site equipped with cameras.

Initially Rozell posted the images on the high school’s website. “We didn’t have much traffic,” he recalls. No one imagined that within a short time the photographs would be sought after by the world’s major Holocaust archives: In the wake of a cooperative effort between Rozell and the Holocaust memorial site at Bergen-Belsen, the history teacher was flooded with emails from people in different countries who had identified themselves in the photographs. Grasping that he had come upon a huge story, Rozell decided to research it in depth.

Haaretz covered ongoing efforts to identify the woman closest to the camera in the frame as of 2017, and reported on the death of former American soldier Frank Towers in July 2016. On a website for a Bergen-Belsen Memorial in Europe, the image appears on a page about the camp, noting it was “initially set up for Jewish hostages whom the SS had said they would release — in exchange for Germans interned abroad, foreign currency or commodities valuable to the war effort.”

The image is also included in a United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) collection, “LIBERATION — Germany: General — Train to Magdeburg/Farsleben.” Images in that collection were dated April 13 through April 16 1945. On a separate page in the collection, USHMM notes that the “woman has been possibly identified as Shlima Spitzer.”

A Reddit post about a “powerful photo” of Jewish prisoners rescued from a train en route to Bergen-Belsen in April 1945 was accurately described by the poster. However, the image itself remained forgotten for decades in a San Diego home until a New York State history teacher’s project and website began connecting surviving liberated prisoners and the soldiers who intercepted the train.

- This is such a powerful photo. It was taken in April, 1945, by Major Clarence Benjamin and shows a train of Jewish prisoners that had been intercepted by Allied Forces. This is the moment they learned that the train would not be heading to a Concentration Camp and they had been liberated.

- Jewish prisoners of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany, on a transport to Theresienstadt north of Prague, moments after they were liberated by the US forces on April 1945. [1920 x 2304]

- Jewish prisoners after being liberated from a death train, 1945

- Jewish prisoners of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany, on a transport to Theresienstadt north of Prague, moments after they were liberated by the US forces on April 1945.

- What are the best photographs in history?

- “A Train Near Magdeburg”

- Holocaust Survivors, Liberators Reunited

- Holocaust Survivors Reunite With WWII Liberators

- A Train Near Magdeburg: A Teacher's Journey into the Holocaust, and the reuniting of the survivors and liberators, 70 years on

- 72 Years Later, Woman From Iconic Holocaust Photo Identified

- U.S. Soldier Frank Towers, Who Rescued 2,500 Jews at End of WWII, Dies at 99

- The Concentration Camp (1943-1945)

- LIBERATION -- Germany: General -- Train to Magdeburg/Farsleben

- A female survivor and her child run up a hill after escaping from a train near Magdeburg and their liberation by American soldiers from the 743rd Tank Battalion and 30th Infantry Division.