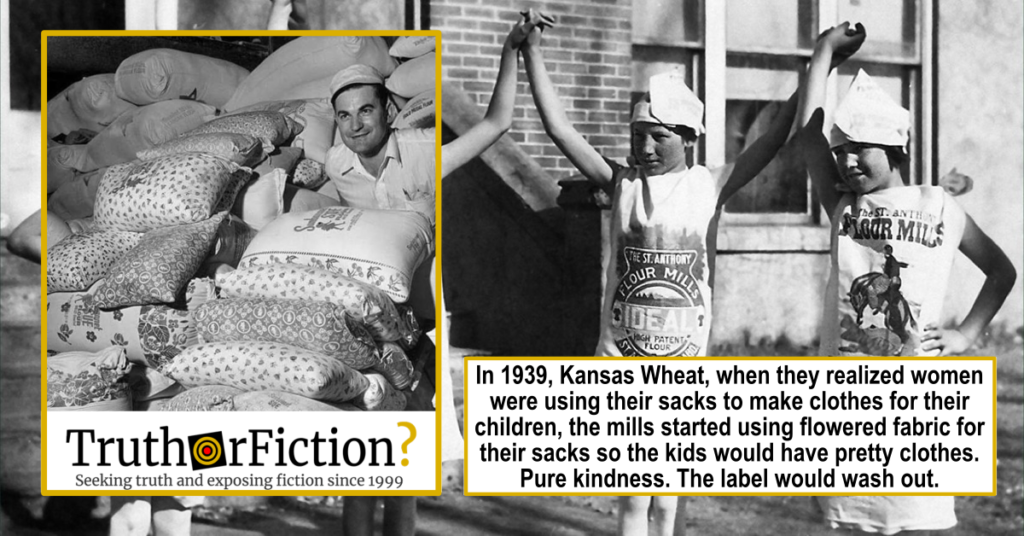

While it may not be a case of deliberately misstating the context, the rediscovery online of a pioneering journalist’s photograph in 1939 by people on social media came with a far more optimistic view of the circumstances behind it than had previously existed.

In September 2019, a user on the photo-based platform Imgur reposted a photo shot by Margaret Bourke-White for Life magazine at a Sunbonnet Sue flour mill in Kansas showing a worker alongside bags of flour made in several different patterns suitable for clothing:

The caption read:

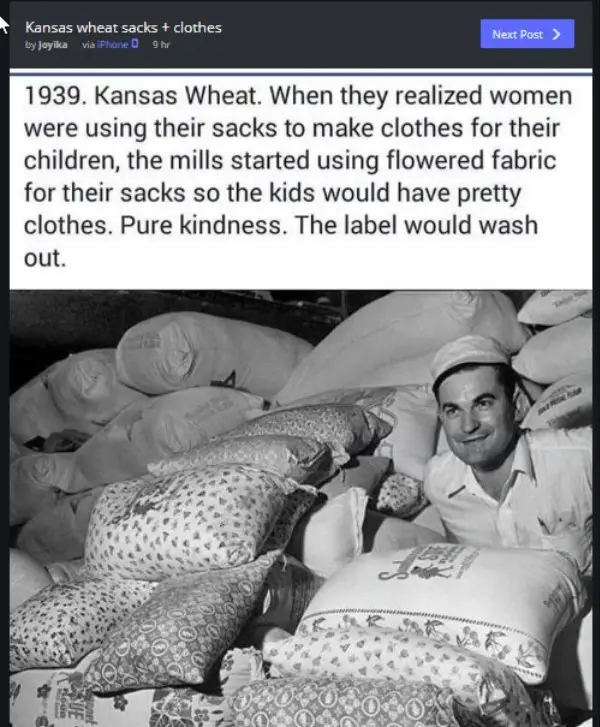

1939. Kansas wheat. When they realized women were using sacks to make clothes for their children, the mills started using flowered fabric for their sacks so the kids would have pretty clothes. Pure kindness. The label would wash out.

It is unclear whether the post was based on a “snapshot in time” published by the blog History Undusted in 2016. But it is indisputable that flour and feed sacks were turned into clothing by various manufacturers.

However, a study published in 2009 by Kendra Brandes did not list “pure kindness” as the rationale behind it. Brandes, an associate professor of Family and Consumer Sciences at Bradley University, found that some feed sack makers began producing printed fabrics in the 1920s, it did not become a widespread practice until the following decade:

Feed sacks were designed with easy use in mind. Sacks were stitched along one side and across the bottom with a simple chain stitch so that stitching could be removed by clipping the top loop and pulling out the entire line of stitching very quickly. The string could be saved for other uses. More effort was made to use logo inks that were easily washed out. A few bag manufacturers printed patterns for dolls, doll clothes, and other items on the backs of the feed sacks. Items could be cut directly from the sack and quickly sewn. Sacks were sometimes hemmed before being stitched as a bag so that when the chain stitching was removed, the bag was ready to use as an apron or tablecloth, depending on the size of the bag.

Marketing tactics were redirected from the farmer to the farm wife as bag manufacturers and mills attempted to “attract feminine attention to get the masculine dollar.” This shift in target market continued over the next few decades and did not go unnoticed by feed stores employees. A quote from a feed salesman in 1948 probably echoed the sentiment of many of his fellow feed merchants. “Years ago they used to ask for all sorts of feeds, special brands, you know. Now they come over and ask me if I have an egg mash in a flowered percale. It ain’t

natural.”

Brandes also observed that while there is no shortage of fabrics in present day, that the practice of upcycling the sacks into clothing created more of a connection between the families involved and their creations.

“The memories of feed sacks collected from the women and men interviewed provide valuable insight into the importance of working together with the elements of our near environment (fabrics, foods, and housing) that shape our lives,” she wrote. “This is the cultural heritage of rural America.”

The Smithsonian also recognized the practice as not only a necessity during World War II, but a source of income for women who would sell their upcycled designs.

In 2017, Brandes’ work formed the basis of a story published by Slate focusing on the popularity of the repurposed flour sacks. We contacted Brandes seeking additional comment.