In December 2019, a graphic circulated online that questioned the dominant narrative on (and perhaps had some readers rethinking their views about) the pirate culture of the 17th century.

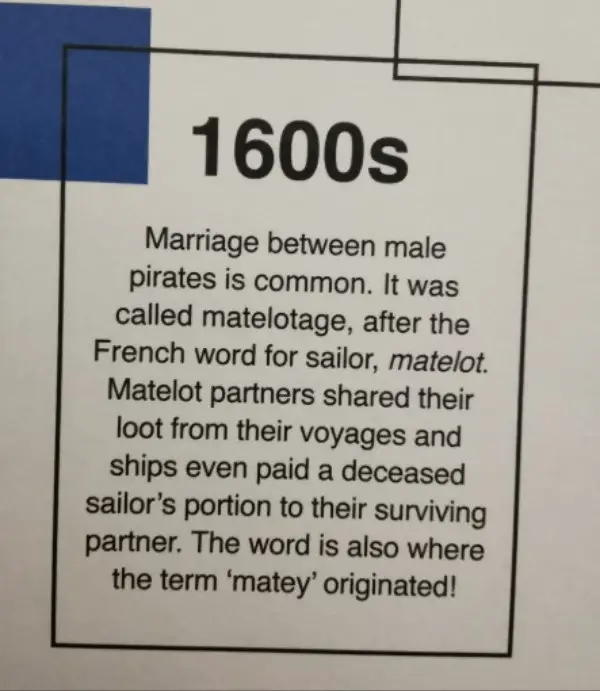

A photograph, taken from the 2019 book The Queeriodic Table: A Celebration of LGBTQ+ Culture, showed a short portion of text:

According to the book:

1600s: Marriages between male pirates is common. It was called matelotage, after the French word for sailor, matelot. Matelot partners shared their loot from their voyages and ships even paid a deceased sailor’s portion to their surviving partner. The word is also where the term “matey” originated.

The concept of matelotage is real, but the claim promoted in the graphic is romanticized, at least going by the findings of historian B.R. Burg in his definitive 1982 book Sodomy and the Pirate Tradition: English Sea Rovers in the Seventeenth-Century Caribbean, which delved into both the practice and the effects of those partnerships.

For one thing, he breaks down the idea that matelotage was commonplace and guided by mutual romantic interest, writing:

How often men joined with another member of their crew, the average duration of pirate marriages, or what proportion of buccaneers ignored opportunities for close relationship with other men and simply lived lives of unrestricted promiscuity cannot even be guessed.

Elsewhere in the book he explained further:

As practiced by buccaneers on Hispaniola in the seventeenth century, matelotage was probably no more than a master-servant relationship originating in cases of men selling themselves to other men to satisfy debts or to obtain food. In many cases matelots were no more than slaves, overworked, beaten, sexually abused, murdered, or sold by their owners. However, the generally recognized bond it created between men and the understanding that an inviolable attachment existed between the two as long as the master wanted it to remain so gave matelotage a sacrosanct aura among buccaneers.

According to Burg, these buccaneers were more likely to dissolve their partnerships than married heterosexual couples, since their unions operated under “the absence of ecclesiastical approval, legally binding pronouncements, a home, and children.” Matelots would be sold between pirates in the course of the agreement. But once the terms of that partnership expired, he added, a matelot could choose a new partner if he wished.

Marc Nucup, the public historian for the Mariners’ Museum and Park in Virginia, did confirm the Queeriodic Table definition of matelotage, but added that “the practice of homosexuality among pirates does not appear to have been more or less prelavent than in the general population.”

Matelotage partnerships, Nucup said, were “more of a mentor-mentoree relationship where a new sailor would be paired with an experienced sailor in order to teach them seamanship.” In these arrangements, he said, one party might inherit loot from the other. The French Army, he said, also allowed for these types of partnerships.

“Among boucaniers (hunters) in the Carribean, a similar relationship to matelotage existed, but was more akin to a master-apprentice relationship,” Nucup explained. “This sort of arrangement appears to have been limited to traditional boucaniers in the 1620s-1670s and did not extend into the Golden Age of Piracy.”

Burg’s findings also appear to corroborate the meme’s claims regarding a matelot’s claim to their partner’s loot and possessions. Burg wrote:

According to European law, wives or children were entitled to all property of the deceased, but in the Caribbean wives and children were as uncommon as observance of legal niceties, and when a man died all goods went to his partner, whether master or matelot. So strong was the practice that after his attack on Maracaibo, the pirate captain L’Olonnais was careful to make certain that the booty was divided not only among the survivors, but that the portions of those killed were distributed to their servants. On occasion, the mutual ownership of property was even formalized by setting down in writing the agreement that all goods belonged to the survivor.

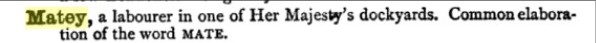

The alleged connection between matelots and the term “matey” is also unclear; The Slang Dictionary: Etymological, Historical, Andecdotal, first published in 1859, lists it as a “common elaboration of the word ‘mate,'” and says it refers to “a labourer in one of Her Majesty’s dockyards”:

Nucup told us that “mate,” taken from the Middle Low German word “māt,” meaning comrade, first appears in English literature around 1380. By the 1480s, he said, it took on a maritime meaning as a term for an assistant. However, he added, “matey” only appears in literature by 1794.

“[That] is is way beyond the Age of Piracy and would be anachronistic for a pirate to use,” he said.

We contacted Summersdale Publishers, which released The Queeriodic Table, attempting to seek comment from Dyer.

Update, 12/18/19, 8:28 a.m.: Added comments from Marc Nucup, public historian for the Mariners’ Museum and Park. — ag