In an ongoing online debate over whether centrists enable fascists, a December 16 2019 tweet purportedly showed an authentic New York Times article from 1932, which reported that “German centrists” believed that Nazis would become “more moderate” if they were included in the civic process:

In the tweet, the user wrote:

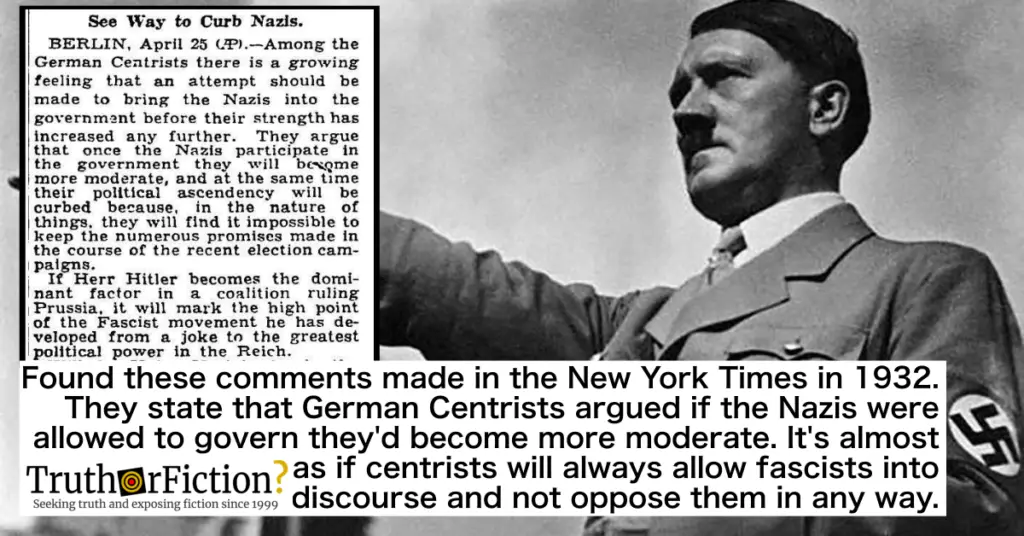

Just found these comments made in a the New York Times in 1932. They state that the Germany Centrists argue that if the Nazis are allowed to govern they’ll become more moderate. It’s almost as if centrists will always allow fascists into discourse and not oppose them in any way.

A photograph with a microfiche appearance showed a newspaper clipping dated April 25 1932, bylined Berlin, and with an Associated Press attribution. The clipping showed a story which reported that centrists in that point in history believed that Adolf Hitler’s fascist movement — which was at the time still nascent — rested on “impossible to keep … numerous promises made in the course of recent election campaigns.”

Furthermore, German centrists were reported as broadly believing that members of the Nazi party to have a participatory role in the government of the time would cause them to “become more moderate”:

…See Way to Curb Nazis

Berlin, April 25 (AP)

Among the German centrists there is a growing feeling that an attempt should be made to bring the Nazis into the government before their strength has increased any further. They argue that once the Nazis participate in he government they will become more moderate, and at the same time their political ascendency will be curbed because, in the nature of things, they will find it impossible to keep the numerous promises made in the course of the recent election campaigns.

If Herr Hitler becomes the dominant factor in a coalition ruling Prussia, it will mark the high point of the fascist movement he has developed from a joke to the greatest political power in the Reich.

The claim was not newly discovered in December 2019; it also circulated on Reddit in November 2016:

That post linked to a November 12 2016 tweet which included a screenshot of the same column, itself threaded to a separate 1931 news article with roughly the same viewpoint:

The column was one of many works cited in an undated piece titled “A Failure Of Narrative: A comparative analysis of the New York Times and American media at the dawn of Nazi Germany, 1929-1933” by former Business Insider journalist Harrison Jacobs. In it, Jacobs began:

In 1933, as the world watched, the last vestiges of the flimsy democracy that was the Weimar Republic were swept away by Hitler. This event did not happen secretly or with indifference. Despite the multitude of problems that plagued the rest of the world—from the sweep of communist and totalitarian governments springing up to the collapse of the global economic order—the rise of Nazi Germany was watched intently, derided and applauded at the same time. This mixed reaction, a reaction of not exactly knowing how to feel, was met doubly in America. It is easy now to look back upon the rise of Nazi Germany with the hindsight of one who knows what comes after, it is the sort of feeling one gets upon re-watching a particularly suspenseful movie—one knows what is going to happen, one expects it, yet they root so valiantly against it, hoping that at the very last instant the conflicted hero will choose good, not evil. It is therefore hard for us to look back upon the public of the 1930s and not write a revisionist history where America always condemned the Nazis and the nation was always gearing to fight another great war for democracy. The true narrative is far more murky and conflicted.

Jacobs maintained that despite the eerie focus through a historical lens, “journalism of the time did not fail in its coverage of the major events of the fall of Weimar Germany and the rise of Nazi Germany, often reporting minute stories such as court cases involving minor National Socialist players and small gains in party representation in the Reichstag.”

However, he assessed that by and large American newspapers of the time “failed to ascertain the larger meaning of the events they covered and wildly underestimated the validity of Hitler’s influence and the staying power of the movement.”

In the section in which the citation appeared, Jacobs wrote of collected archival news items of the day:

Despite the narrative presented by the largest media outlets, there was a small minority of papers that were openly pessimistic about the direction that Germany was headed. The Times Picayune, on the elections: “…the moderates have to face the unpleasant fact that the extremist gains were at their expense.” The Detroit Free Press bluntly stated, “The republican group have had their chance and failed.”

The general press narrative was such that the American reading public was not fully aware of “the extent of the German economic and political discontent.” As has become standard in this analysis, Hermann asserted, “The sins of the press were actually ones of omission rather than commission, obtuseness rather than conspiracy.” Even at the end of April, the Times continued in their belief that the Nazis were not who they said they were. They accepted the argument of the German centrists that “once the Nazis participate in the government they will become more moderate at the same time their political ascendancy will be curbed…”

When the Bruening government fell in June [1932], the New York Times still did not adequately portray the danger that the government change portended or what the rise of Von Papen meant. A Washington Post headline captured what a more incisive press reaction looked like with “NAZIS HAIL FALL OF BRUENING AS CLINCHING RULE.” Similarly, the Philadelphia Inquirer headline read “REICH FACES FASCIST RULE UNDER HITLER OR DICTATORSHIP BY REICHSWEHR.” The Times, by contrast, decided that the effects of the von Papen cabinet would “not prove to be so great as many will hastily predict.” They further pointed to Hindenburg as “a tower of strength.”

After World War I ended, conditions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles paved the way for Hitler’s populist movement to take root. When the Weimar Republic collapsed in June 1932, Nazis were waiting in the wings. Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933:

Following the appointment of Adolf Hitler as German chancellor on January 30, 1933, the Nazi state (also referred to as the Third Reich) quickly became a regime in which citizens had no guaranteed basic rights. The Nazi rise to power brought an end to the Weimar Republic, the German parliamentary democracy established after World War I. In 1933, the regime established the first concentration camps, imprisoning its political opponents, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others classified as “dangerous.” Extensive propaganda was used to spread the Nazi Party’s racist goals and ideals. During the first six years of Hitler’s dictatorship, German Jews felt the effects of more than 400 decrees and regulations that restricted all aspects of their public and private lives.

The 1932 New York Times article with a visible headline that read “See Way to Curb Nazis” was published on April 26 1932, and it is available via the paper’s online archive. Moreover, its claims are broadly substantiated — that both “German centrists” and the international news media did not foresee the looming and abrupt rise in fascism in a beaten-down and angry Germany. But the first claim — that the article was authentic and archival versus a history meme — is true and accurate.

- LET'S PUT AN END TO 'HORSESHOE THEORY' ONCE AND FOR ALL

- Adam Khan on Twitter: "1932, NYT: If Nazis are allowed to govern they'll become more moderate because they'll find it impossible to keep their campaign promises"

- A Failure Of Narrative: A comparative analysis of the New York Times and American media at the dawn of Nazi Germany, 1929-1933

- TREATY OF VERSAILLES

- Timeline of Events/1933-1938

- See Way to Curb Nazis.