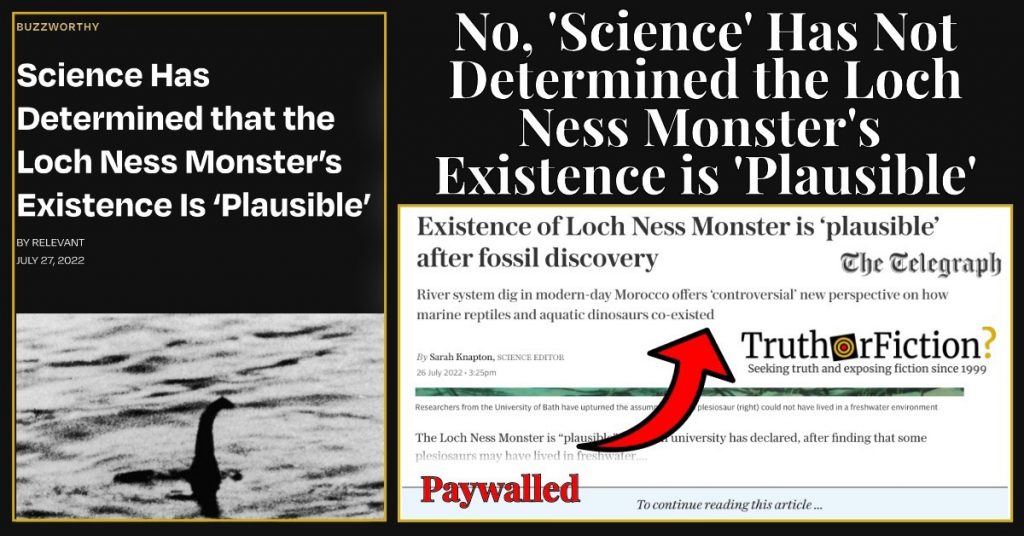

On July 26 2022, several organizations claimed that the existence of the Loch Ness monster had just been deemed “plausible,” an odd story promoted to readers on social media already inured to bizarre developments:

The UK-based Telegraph was one of the first and most viral iterations to hit social media as the story became popular. Unfortunately, the article was hidden behind a hard paywall, leaving readers to share a link to a story that most people could not read.

Fact Check

Claim: In July 2022, scientists discovered the existence of the Loch Ness monster was “plausible.”

Description: Several organizations have reported in July 2022 that the existence of the Loch Ness monster is plausible based on the discovery that some plesiosaurs may have lived in freshwater. This was promoted heavily on social media.

For context, the Loch Ness monster is a cryptid, a creature that “has been claimed to exist but never proven to exist.” Brittanica.com defined the Loch Ness monster in terms relevant to circulating claims that new evidence made its existence plausible (including a decades-old image known as the “surgeon’s photograph,” which was later revealed to be a hoax):

Loch Ness monster, byname Nessie, large marine creature believed by some people to inhabit Loch Ness, Scotland. However, much of the alleged evidence supporting its existence has been discredited, and it is widely thought that the monster is a myth.

Reports of a monster inhabiting Loch Ness date back to ancient times. Notably, local stone carvings by the Pict depict a mysterious beast with flippers. The first written account appears in a biography of St. Columba from 565 AD. According to that work, the monster bit a swimmer and was prepared to attack another man when Columba intervened, ordering the beast to “go back.” It obeyed, and over the centuries only occasional sightings were reported. Many of these alleged encounters seemed inspired by Scottish folklore, which abounds with mythical water creatures.

In 1933 the Loch Ness monster’s legend began to grow. At the time, a road adjacent to Loch Ness was finished, offering an unobstructed view of the lake. In April [1933] a couple saw an enormous animal—which they compared to a “dragon or prehistoric monster”—and after it crossed their car’s path, it disappeared into the water. The incident was reported in a Scottish newspaper, and numerous sightings followed. In December 1933 the Daily Mail commissioned Marmaduke Wetherell, a big-game hunter, to locate the sea serpent. Along the lake’s shores, he found large footprints that he believed belonged to “a very powerful soft-footed animal about 20 feet [6 metres] long.” However, upon closer inspection, zoologists at the Natural History Museum determined that the tracks were identical and made with an umbrella stand or ashtray that had a hippopotamus leg as a base; Wetherell’s role in the hoax was unclear.

Folklore about the Loch Ness Monster dated back to the mid-500s. However, modern stories about the cryptid began popping up again in 1933, when a newly completed road made Loch Ness more visible; the lore was immediately followed by known hoaxes supposedly providing evidence of the creature’s existence.

As for the initial Telegraph article, anyone who visited the page without a subscription could only see a half-sentence of its content atop the paywall. A subheading indicated “controversial” evidence had been purportedly discovered — in Morocco, not Scotland:

Existence of Loch Ness Monster is ‘plausible’ after fossil discovery River system dig in modern-day Morocco offers ‘controversial’ new perspective on how marine reptiles and aquatic dinosaurs co-existed’

River system dig in modern-day Morocco offers ‘controversial’ new perspective on how marine reptiles and aquatic dinosaurs co-existed

The Loch Ness Monster is “plausible”, a British university has declared, after finding that some plesiosaurs may have lived in freshwater….

Unlocking the article revealed details underscoring its claims, none of which seemed to actually make the existence of the Loch Ness monster “plausible”:

The Loch Ness Monster is “plausible”, a British university has declared, after finding that some plesiosaurs may have lived in freshwater.

Nessie proponents have long believed that the creature of Scottish folklore could be a prehistoric reptile, with grainy images and eyewitness accounts over the years hinting that the beast has a long-neck and small head similar to a plesiosaur.

However, skeptics argue that even if a plesiosaur lineage had survived into the modern era, the creatures could not have lived in Loch Ness because they needed a saltwater environment.

Now, the University of Bath has found fossils of small plesiosaurs in a 100-million-year-old river system that is now in Morocco’s Sahara Desert, suggesting they did live in freshwater.

The Telegraph stated behind a paywall that evidence located in Morocco suggested that plesiosaurs did live in freshwater, a big leap from “the Loch Ness monster plausibly exists.” Brittanica.com’s entry on plesiosaurs noted that they existed in “the late Triassic Period into the late Cretaceous Period (215 million to 66 million years ago),” and, despite how long certain periods of time may feel, 1933 was not 66 million years ago.

The article later reported:

Dr Nick Longrich, corresponding author on the paper, said: “We don’t really know why the plesiosaurs are in freshwater.

“It’s a bit controversial, but who’s to say that because we paleontologists have always called them ‘marine reptiles’, they had to live in the sea? Lots of marine lineages invaded freshwater.”

The first complete skeleton of a plesiosaur was first found in Lyme Regis, Dorset, in 1823 by Mary Anning, an English fossil hunter.

The creature was found to have a small head, long neck and four flippers and was named “near lizard” because it was thought to more closely resemble modern reptiles, compared to the Ichthyosaurus, which had been found in the same rock strata just a few years earlier.

While the subheading alluded to “controversial” findings, a quoted author on the research described the “controversial” evidence to be plesiosaurs in freshwater habitats, not the Loch Ness monster appearing in the 1930s. The article concluded with content from a University of Bath press release — and a longer quote stating the Loch Ness monster was “on one level, plausible.”

In one of its final sentences, the Telegraph admitted that plesiosaurs went extinct 66 million years before the 20th century Loch Ness tales spread:

A press release from the University of Bath said the new discovery showed that the Loch Ness Monster was “on one level, plausible”.

“Plesiosaurs weren’t confined to the seas, they did inhabit freshwater,” the release added, but also pointed out that the fossil record still showed that plesiosaurs had died out at the same time as the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago.

The new research was published as a pre-print.

News about the Loch Ness monster was credited to the University of Bath, and its press release was available on Phys.org. It was titled “Plesiosaur fossils found in the Sahara suggest they weren’t just marine animals,” and it began:

Fossils of small plesiosaurs, long-necked marine reptiles from the age of dinosaurs, have been found in a 100-million year old river system that is now Morocco’s Sahara Desert. This discovery suggests some species of plesiosaur, traditionally thought to be sea creatures, may have lived in freshwater.

Plesiosaurs, first found in 1823 by fossil hunter Mary Anning, were prehistoric reptiles with small heads, long necks, and four long flippers. They inspired reconstructions of the Loch Ness Monster, but unlike the monster of Lake Loch Ness, plesiosaurs were marine animals—or were widely thought to be.

Now, scientists from the University of Bath and University of Portsmouth in the U.K., and Université Hassan II in Morocco, have reported small plesiosaurs from a Cretaceous-aged river in Africa.

The fossils include bones and teeth from three-meter long adults and an arm bone from a 1.5 meter long baby. They hint that these creatures routinely lived and fed in freshwater, alongside frogs, crocodiles, turtles, fish, and the huge aquatic dinosaur Spinosaurus.

These fossils suggest the plesiosaurs were adapted to tolerate freshwater, possibly even spending their lives there, like today’s river dolphins.

Per the University of Bath’s press release, the findings were not that the Loch Ness monster’s existence (in the manner we understand the “Loch Ness monster” as a concept) was “plausible.” In actuality, the findings held that a long-extinct prehistoric reptile may have “adapted to tolerate freshwater.”

“Loch Ness” appeared three times in the entirety of the press release, twice in the excerpt above. The third was the final paragraph, stating:

But what does this all mean for the Loch Ness Monster? On one level, it’s plausible. Plesiosaurs weren’t confined to the seas, they did inhabit freshwater. But the fossil record also suggests that after almost a hundred and fifty million years, the last plesiosaurs finally died out at the same time as the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago.

A July 26 2022 paywalled Telegraph article (followed by many others) made the predictably viral claim that a novel discovery by scientists indicated the existence of the Loch Ness monster was “plausible.” That claim was undermined by the researchers’ press release — which did mention the Loch Ness monster in order to describe plesiosaurs. That same press release noted that “the last plesiosaurs finally died out … 66 million years ago.” Finally, the evidence described in the research’s press release originated in Morocco, and had almost nothing to do with the Loch Ness monster beyond its purported resemblance to the long-dead plesiosaurs.

- Loch Ness Monster plausible | Twitter

- Loch Ness Monster plausible | Twitter

- Existence of Loch Ness Monster is ‘plausible’ after fossil discovery

- Cryptid | Merriam-Webster

- Loch Ness monster | Brittanica.com

- Plesiosaur | Brittanica.com

- Plesiosaur fossils found in the Sahara suggest they weren't just marine animals