On April 4 2021, Twitter user Elizabeth Jacobs PhD (@TheAngryEpi) tweeted about political claims involving quarantine-related suicides in 2020, contrasted with March 2021 data about mortality rates for the year before:

Jacobs said:

Politicians told us repeatedly that lockdowns were causing increased numbers of deaths by suicide. We kept asking to see the data. Now, we have it, and apparently, this was not true. In 2020, deaths by suicide were lower than in the previous three years.

Jacobs’ tweeted statement was concise, but it still involved several layers of information.

‘Politicians Told Us Repeatedly That Lockdowns Were Causing Increased Numbers of Deaths by Suicide’

We didn’t have to search back that far to find social media posts connecting “lockdowns,” or more specifically, pandemic-related quarantine orders, to suicide rates.

Tweets expressing the generalized notion that stay-at-home measures led to an uptick in suicide were common — almost nearly conventional wisdom, in fact — in late March and early April 2021:

But Jacobs pointed to politicians pushing the claim that lockdowns led to an increase in suicide, while commenters in general were reiterating the claim in the tweets above. On March 25 2020, in the pandemic’s earliest days, ABC News published “Fact checking Trump’s claim about suicides if the economic shutdown continues.”

It reported:

As some in President Donald Trump‘s inner circle push for loosening social distancing guidelines amid economic fallout from the novel coronavirus outbreak, he has predicted “tremendous death” and “suicide by the thousands” if the country isn’t “opened for business” in a matter of weeks.

[…]

“You’re going to lose more people by putting a country into a massive recession or depression.” Trump said [March 24 2020] in a Fox News town hall. “You’re going to lose people. You’re going to have suicides by the thousands.”

One night before [on March 23 2020], at a coronavirus task force briefing, the president said, “I’m talking about where people suffer massive depression, where people commit suicide, where tremendous death happens… I mean, definitely would be in far greater numbers than the numbers that we’re talking about with regard to the virus.”

Two months later, a May 22 2020 U.S. News and World Report article included commentary from mental health experts about the often-repeated refrain that lockdown caused suicides to spike. That piece largely referenced individual deaths, not “clusters” of suicidal behavior:

COVID-19 has been associated with other suicides that drew widespread media attention, including a German state finance minister who appears to have taken his own life while worried about economic disaster, a British teenager distressed by social distancing measures, and an Italian nurse who feared spreading the virus to other people. One county in Washington state reported a surge in deaths by suicide, mostly of men in their 30s and 40s, since the outbreak began.

Researchers fear the phenomenon could become more widespread: In a commentary published last month [April 2020] in medical journal The Lancet Psychiatry, an international group of suicide experts advocated “urgent consideration” to prevent a rise in suicide rates, especially as COVID-19 – and its [devastating] economic impact – drag on for months.

“These are unprecedented times,” the authors wrote. “The pandemic will cause distress and leave many people vulnerable to mental health problems and suicidal behaviour.”

In 2018, the most recent year for which data is available, more than 48,000 Americans died by suicide, according to the Centers for Disease Control, ranking it the country’s 10th-leading cause of death. And while many countries have seen their suicide rates decline in recent years, in the U.S. the rate has increased 35% since 1999, from 10.5 deaths per 100,000 people to 14.2, an alarming rise that’s also prompted a call to action among health professionals.

In the absence of longitudinal data, journalists relied on expert speculation and individual deaths. A November 2020 Washington Post article centered around a young man’s death, but it also included a broader scope of possibility:

America’s system for monitoring suicides is so broken and slow that experts won’t know until roughly two years after the pandemic whether suicides have risen nationally. But coroners and medical examiners are already seeing troubling signs.

[…]

Even as suicide rates have fallen globally, they have climbed every year in the United States since 1999, increasing 35 percent in the past two decades. Still, funding and prevention efforts have continued to lag far behind those for all other leading causes of death.

Then came the pandemic.

Experts warned that the toxic mix of isolation and economic devastation could generate a wave of suicides, but those dire predictions have resulted in little action.

A November 2020 editorial in medical journal BMJ (“Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic,” with the subheading, “Prevention must be prioritised while we wait for a clearer picture”) began with an acknowledgement of widespread speculation about a possible rash of suicides globally, but noted that none of the available evidence had yet validated the concerns.

That editorial added that much of the information available at that time — again, November 2020 — was preliminary or had not yet been peer-reviewed:

As many countries face new stay-at-home restrictions to curb the spread of covid-19, there are concerns that rates of suicide may increase—or have already increased. Several factors underpin these concerns, including a deterioration in population mental health, a higher prevalence of reported thoughts and behaviours of self-harm among people with covid-19, problems accessing mental health services, and evidence suggesting that previous epidemics such as SARS (2003) were associated with a rise in deaths by suicide.

[…]

Supposition, however, is no replacement for evidence. Timely data on rates of suicide are vital, and for some months we have been tracking and reviewing relevant studies for a living systematic review. The first version in June [2020] found no robust epidemiological studies with suicide as an outcome, but several studies reporting suicide trends have emerged more recently. Overall, the literature on the effect of covid-19 on suicide should be interpreted with caution. Most of the available publications are preprints, letters (neither is peer reviewed), or commentaries using news reports of deaths by suicide as the data source.

As of November 2020, the author added:

It is still too early [in November 2020] to say what the ultimate effect of the pandemic will be on suicide rates. Data so far provide some reassurance [suicide rates had not risen], but the overall picture is complex. The pandemic has had variable effects globally, within countries and across communities, so a universal effect on suicide rates is unlikely. The impact on suicide will vary over time and differ according to national gross domestic product and individual characteristics such as socioeconomic position, ethnicity, and mental health.

In January 2021, the New York Times followed with “Will the Pandemic Result in More Suicides? (It’s too soon to know. But some recent data, especially from specific groups, is cause for worry)”, largely lamenting the absence of solid information — but advancing the idea that pandemic preventive measures exacerbated the rate of suicide:

Studying the effect of Covid-19 on suicide rates could inform a longstanding scientific debate about the extent to which the behavior is driven by brain chemistry compared with external stressors. If Covid-19 increases suicidal behavior — there was a rise in suicide among older adults in Hong Kong in 2003, the year of the SARS outbreak — that might lend weight to the idea that socioeconomic pressures, like job loss or isolation, are key triggers. “But as with any scientific debate, the answer is always both,” Nestadt adds. “This is a multifactorial behavior.”

In February 2021, NPR reported on warnings from child psychologists. The segment relied heavily on anecdotes and small patterns, not peer-reviewed studies:

“Across the country, we’re hearing that there are increased numbers of serious suicidal attempts and suicidal deaths,” says Dr. Susan Duffy, a professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at Brown University.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between April and October 2020, hospital emergency departments saw a rise in the share of total visits that were from kids for mental health needs.

Now, there are no nationwide numbers on suicide deaths in 2020 yet, and researchers have yet to clearly link recent suicides to the pandemic. Yet on the ground, there’s growing concern.

NPR spoke with providers at hospitals in seven states across the country, and all of them reported a similar trend: More suicidal children are coming to their hospitals — in worse mental states.

NPR built their reporting around anecdotal information, adding that no firm, verifiable evidence about whether those fears bore out existed.

‘Now, We Have It, and Apparently, This Was Not True. In 2020, Deaths by Suicide Were Lower Than in the Previous Three Years.’

In Jacobs’ tweet, she said that as of late March or early April 2021, better data became available — and it showed that the claims about the effects of quarantines on mental health, which she characterized as political in nature, were not supported by the numbers.

Jacobs linked to a March 31 2021 editorial in JAMA (The Journal of the American Medical Association), “The Leading Causes of Death in the US for 2020.” The editorial did not focus on suicide rates, primarily or otherwise — it was instead a broad look at initial mortality figures for the year 2020. It began:

Vital statistics data provide the most complete assessment of annual mortality burden and contribute key measurements of the direct and indirect mortality burden during a public health pandemic. While mortality statistics have historically been produced annually, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced a pressing need for the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) to rapidly release reliable provisional mortality data. Provisional estimates indicate a 17.7% increase in the number of deaths in 2020 (the increase in the age-adjusted rate was 15.9%) compared with 2019, with increases in many leading causes of death. The provisional leading cause-of-death rankings for 2020 indicate that COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death in the US behind heart disease and cancer.

To understand the content by which the editorial presented its initial calculations, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention page (“Understanding Death Data”) explained and defined the concept of provisional data:

What are Provisional Data?

Provisional data are preliminary data that may not yet be complete. Provisional data reports are based on a current flow of new and updated records received from states. These data may be released monthly or quarterly and are subject to change as information continues to be collected and analyzed – as such, they are estimates that may differ from the final count.Provisional data are not final and must always be used with the understanding that numbers and information may change as the data becomes more complete.

What are Final Data?

Final (annual) data are released only after we have received all death records from the states and have fully reviewed the data for completeness and quality.Final data contain the most accurate and complete information we provide. These official records are used in publications and data visualizations, and for investigation and research, among other uses.

Why does CDC release provisional data?

The benefit of releasing provisional data is timeliness. Final data takes time to ensure accuracy and completeness. Faster and more frequent data releases may signal changes in trends and offer investigators clues about emerging public health events. Preliminary data allows us to track and monitor the ongoing impact of a crisis and take smarter action to save lives.

In some of the excerpts above, news organizations referenced “the most recent year for which data is available,” which was 2018 in May 2020. Final numbers and information invariably lag behind provisional data, but it can be used in the interim to formulate preliminary responses.

In the JAMA editorial, the authors note that final “mortality data will be available approximately 11 months after the end of the data year” from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS); figures presented were “provisional, based on currently available death certificate data from the states to the NCHS.”

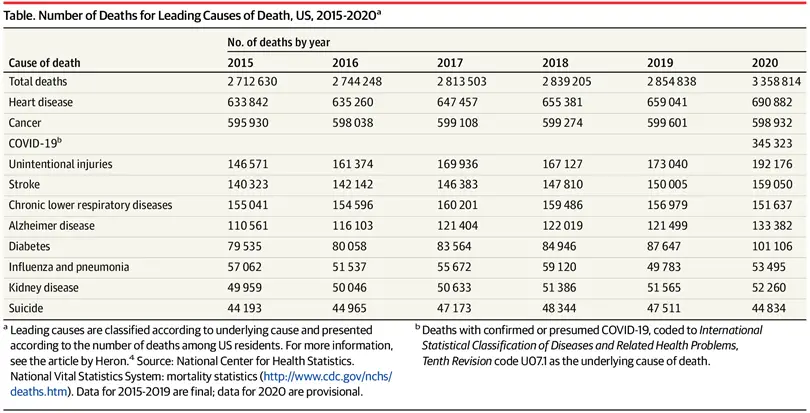

The report continued, with the following text bookending the table in Jacobs’ tweet:

Shifting Trends in Mortality

The provisional number of deaths occurring in the US among US residents in 2020 was 3,358,814, an increase of 503,976 (17.7%) from 2,854,838 in 2019 (Table). Historic trends in mortality show seasonality in the number of deaths throughout the year, with the number of deaths higher in the winter and lower in the summer. The eFigure in the Supplement shows that death counts by week from 2015 to 2019 followed a normal seasonal pattern, with higher average death counts in weeks 1 through 10 (n = 58,366) and weeks 35 through 52 (n = 52,892) than in weeks 25 through 34 (n = 50,227). In contrast, increased deaths in 2020 occurred in 3 distinct waves that peaked during weeks 15 (n = 78,917), 30 (n = 64,057), and 52 (n = 80,656), with only the latter wave aligning with historic seasonal patterns.

Trends in Leading Causes of Death

The Table also presents leading causes of death in the US for the years 2015 to 2020. According to provisional data, in 2020, there were notable changes in the number and ranking of deaths compared with 2019. COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death in 2020, with an estimated 345,323 deaths, and was largely responsible for the substantial increase in total deaths from 2019 to 2020. Substantial increases from 2019 to 2020 also occurred for several other leading causes. Heart disease deaths increased by 4.8%, the largest increase in heart disease deaths since 2012. Increases in deaths also occurred for unintentional injury (11.1%), Alzheimer disease (9.8%), and diabetes (15.4%). Influenza and pneumonia deaths in 2020 increased by 7.5%, although the number of deaths was lower in 2020 than in 2017 and 2018. From 2019 to 2020, deaths due to chronic lower respiratory disease declined by 3.4% and suicide deaths declined by 5.6%.

In a section titled “Understanding Mortality in the Context of a Pandemic,” the authors addressed a specific subset of deaths due to unintentional injury, and the inclusion of drug overdoses in that category:

… Most of the increase in deaths from 2019 to 2020 was directly attributed to COVID-19. However, increases were also noted for several other leading causes of death. These increases may indicate, to some extent, underreporting of COVID-19, ie, limited testing in the beginning of the pandemic may have resulted in underestimation of COVID-19 mortality. Increases in other leading causes, especially heart disease, Alzheimer disease, and diabetes, may also reflect disruptions in health care that hampered early detection and disease management. Increases in unintentional injury deaths in 2020 were largely driven by drug overdose deaths. Final mortality data will help determine the effect of the pandemic on concurrent trends in drug overdose deaths.

Finally, the table provided raw counts by mortality cause for the years 2015 through 2020:

Across the years listed, suicide deaths peaked (in count, not percentage) in 2018, with 48,344 deaths to the 44,834 suicide deaths counted in provisional data for 2020. Unintentional injury deaths were lowest in 2015 (146,571), and highest in the provisional 2020 data (192,176); the figure was up by nearly 20,000 from 2019 (173,040).

Summary

A tweet claimed that politicians “told us repeatedly that lockdowns were causing increased numbers of deaths by suicide” in 2020; we linked a very early instance during which former United States President Donald Trump raised an objection to stay-at-home orders on March 23 2020. Jacobs further stated that people “kept asking to see the data,” which was largely unavailable for 2020 — in its place, speculative news stories and anecdotes (neither of which regularly go through a peer review process) were exceedingly common. Finally, she said that in “2020, deaths by suicide were lower than in the previous three years.” As demonstrated by the table above, that claim was true — provisional data cited in a March 31 2021 JAMA editorial included those figures, and noted that suicide deaths declined by 5.6 percent in 2020.

- "Politicians told us repeatedly that lockdowns were causing increased numbers of deaths by suicide. We kept asking to see the data. Now, we have it, and apparently, this was not true. In 2020, deaths by suicide were lower than in the previous three years."

- There will be a time when more people are committing suicide because of Covid restrictions than actually dying of Covid .

- If Lockdown happens again , there'll be more suicide deaths than covid deaths ???? #COVIDSecondWave lockdown isn't a solution. No relief for hospitality sector, if u cant support, kindly do not restrict us from earning livelihood

- The push for vaccine passports comes from the same governments that told us “safety” meant hospital patients dying alone, families going hungry, and children being isolated to the point of suicide. Like lockdown, covid passes have nothing to do with health. This is about control.

- Things that are more dangerous than COVID for children: -child abuse -suicide -obesity -vision problems -addiction -eating disorders -learning loss -parental unemployment -...etc. Things policy makers have considered when making decisions about lockdowns for children: -COVID

- Fact checking Trump's claim about suicides if the economic shutdown continues

- Will Suicides Rise Because of COVID-19?

- For months, he helped his son keep suicidal thoughts at bay. Then came the pandemic.

- Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic

- Will the Pandemic Result in More Suicides?

- Child Psychiatrists Warn That The Pandemic May Be Driving Up Kids' Suicide Risk

- The Leading Causes of Death in the US for 2020

- Understanding Death Data