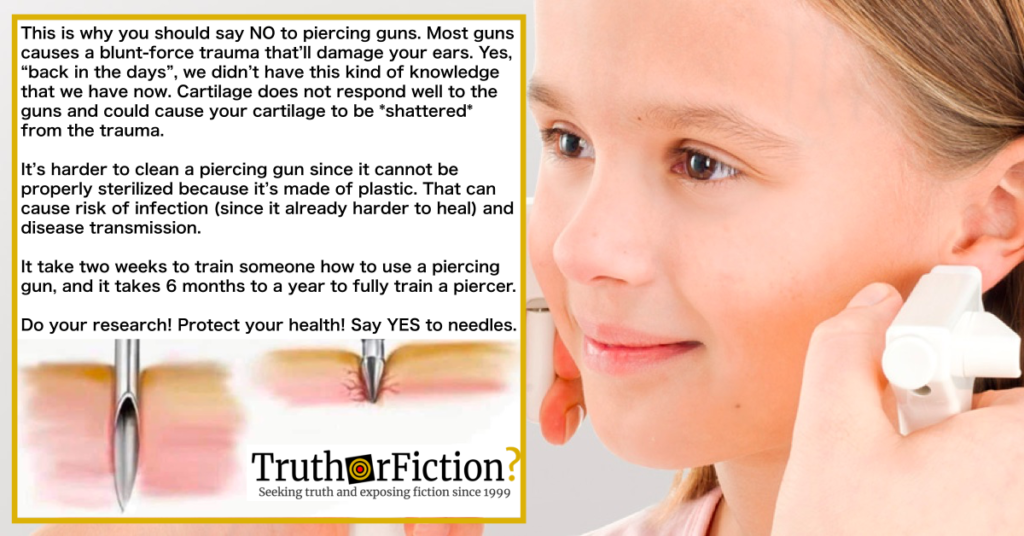

On December 29 2019, Facebook user Stephanie Lipscy shared the following post beginning with “say NO to piercing guns,” alongside an illustration of an ear being pierced:

Lipscy said that the use of ear piercing guns caused “a blunt-force trauma” that is always damaging to ears, claiming that until recently, “we didn’t have this kind of knowledge that we have now” regarding the best way to pierce ears:

This is why you should say NO to piercing guns.

Most guns causes a blunt-force trauma that’ll damage your ears. Yes, “back in the days”, we didn’t have this kind of knowledge that we have now. Cartilage does not respond well to the guns and could cause your cartilage to be *shattered* from the trauma.

It’s harder to clean a piercing gun since it cannot be properly sterilized because it’s made of plastic. That can cause risk of infection (since it already harder to heal) and disease transmission.Why would you want to be pierced with a dull backing of an earring over a sharp, sterilize needle?

It take two weeks to train someone how to use a piercing gun, and it takes 6 months to a year to fully train a piercer the knowledge of proper placements and learning of sterilization of the needles, tapers, jewelry, etc.We don’t all have the same “standard” ear.

Of course there’s risk with any piercings. Proper technique and aftercare is a biggy. Go to a tattoo shop/piercing shop over going to the mall to Claire’s. Spend your money to properly get your ears pierced by a *professional piercer*.

Do your research!

Protect your health!

Say YES to needles. ☺️

Lipscy’s post mentioned Claire’s, a nationwide chain of mall stores known (along with Piercing Pagoda) for its ear piercing services using a gun. Although the post contained no citations for its claims, it did feature an illustration of what was presumably an ear being pierced. On the left side of the drawing, a hollow-tipped medical-style needle created a neat aperture in the earlobe flesh. On the right, a blunter earring post appeared to be irregularly tearing the flesh of a lobe, meeting resistance the entire way.

In a little more than a week, the post had been shared over 55,000 times; since the commenting portion of the post was locked to the poster’s friends, no debate over its veracity or accuracy appeared in the comments underneath it.

Immediately, the post’s claims raised a few questions apparent even to those whose familiarity with ear piercing came largely from having attending the piercing of their own or their child’s ears. Claire’s, mentioned in the post, was a common destination for the rite of ear piercing.

However, perhaps as common depending on ability to pay was another prominent and long-available option: piercing at the office of a pediatrician or other doctor. Many pediatricians offer ear piercing for their patients, and pediatricians or their nurses do not seem to be using body piercing-style needles like the one seen in the illustration used for the viral post.

It seemed reasonable to infer from this that doctors and other medical professionals performing ear piercing on children and adults were aware of arguments for and against the use of piercing guns, as well as the rise in professional body piercing and its practices. The Association for Professional Piercers’ (APP) “Safe Piercing” FAQ contained a section on the use of piercing guns, which began:

It is the position of the Association of Professional Piercers that only sterile disposable equipment is suitable for body piercing, and that only materials which are certified as safe for internal implant should be placed in inside a fresh or unhealed piercing. We consider unsafe any procedure that places vulnerable tissue in contact with either non-sterile equipment or jewelry that is not considered medically safe for long-term internal wear. Such procedures place the health of recipients at an unacceptable risk. For this reason, APP members may not use reusable ear piercing guns for any type of piercing procedure.

In a detailed answer, the APP cited sterilization concerns as well as commonly spring-loaded mechanisms exerting force (using often blunt piercing tips) as additional reasons:

Although they can become contaminated with bloodborne pathogens dozens of times in one day, ear piercing guns are often not sanitized in a medically recognized way. Plastic ear piercing guns cannot be autoclave sterilized and may not be sufficiently cleaned between use on multiple clients. Even if the antiseptic wipes used were able to kill all pathogens on contact, simply wiping the external surfaces of the gun with isopropyl alcohol or other antiseptics does not kill pathogens within the working parts of the gun. Blood from one client can aerosolize, becoming airborne in microscopic particles, and contaminate the inside of the gun. The next client’s tissue and jewelry may come into contact with these contaminated surfaces. There is thus a possibility of transmitting bloodborne disease-causing microorganisms through such ear piercing, as many medical studies report.

APP concluded by indicating that standards regarding sterilization and reuse of piercing guns on multiple clients were not nationally adopted, and that the practice continued with little oversight.

Nevertheless, doctors and clinics seemed to eschew that manner of piercing in their practices. Guidance released by the American Academy of Pediatrics on piercing and body modifications in 2017 had largely to do with piercings other than those in earlobes, perhaps reflecting a growing trend of piercing in general (but providing little useful information on the subject of pierced ears.)

Research published in 1990 in the International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology noted that spring-loaded piercing guns in combination with a lack of training seemed to result in higher incidence of embedded earring backs, but recommendations in the research’s abstract hewed to a broader set of practices and did not recommend avoiding piercing guns altogether:

The embedded earring complication may result from improper aseptic technique, insufficient training of personnel at ear-piercing centers, or piercing the ears of young. To diminish the risk of embedded earrings we recommend aseptic technique, proper training, limiting ear piercing to the lobe, frequent cleansing of the lobe, and removal of the earring if signs of infection develop.

In intervening years, the AAP (as opposed to the APP) has weighed in with recommendations for safe piercing, but those guidelines remained focused on the broader context of a piercing versus the manner in which the piercing was done:

Pediatric resident Suzanne Rossi had heard the questions more than once from parents of a newborn, usually at the 2- or 4-month wellness check … Not fully informed herself, she looked into literature on the subject, which she found to be sparse on infants, and shared her findings at a recent Children’s Center Grand Rounds. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), she noted, has one major recommendation: Postpone ear piercings until the child is mature enough to take care of the pierced site herself.

“That’s clearly the best way to reduce the risk of infection,” Rossi said.

Over and over again, when pediatricians commented on the practice of piercing the ears of infants or children, factors such as age and the child’s ability to care for the piercing site came up. Another common recommendation was to avail oneself of pediatricians‘ office piercing if at all possible, versus a kiosk in a mall:

The AAP recommends that your child’s pediatrician or a well-trained nurse pierces your child’s ears, and most doctor’s offices are willing to do the piercing for a fee, which isn’t covered by insurance. If you want to go to a jewelry store to get the piercings done, check to see if the person doing the procedure is a trained professional.

Tattoo parlors and body piercing salons were not mentioned in the guidance we located. More often than not, a “sterile environment” was recommended; a specific type of piercing implement was not.

In instances when a specific pediatric practice explained their ear piercing methodology [PDF], more often than not they described “medical ear piercing.” Typically that involved a proprietary piercing system available only to medical professionals, marketed by a company known as Blomdahl.

The first office linked above provided a series of images to demonstrate “medical ear piercing” using Blomdahl’s system. Sterility concerns raised about piercing guns appeared to be addressed through the use of a “sterile cassette” containing the earrings, discarded after each patient:

Pediatricians were not the only doctors seemingly using guns in a clinical setting to pierce the ears of patients. A Manhattan Beach, California dermatologist shared video of in-office ear piercing to their page, in which a small gun is clearly used to pierce the ears of a child.

Guidance available at sites like MayoClinic.com often recommending avoiding a gun for body piercing, but content with those recommendations appeared to be exclusively pertinent to body piercing (not ear piercing).

The American Academy of Dermatology had scattered recommendations regarding safe ear piercing, and one such instance mentioned guns. But that organization didn’t say guns themselves were unsafe, and advised only to insist on sterile piercing environments:

Some people say piercing guns aren’t the best because they’re hard to keep clean. If your piercer uses a piercing gun, be sure the part that touches you hasn’t been used on anyone else.

In an age of medical spas and other businesses straddling a line of clinical and aesthetic, businesses marketing a hybrid solution between doctors’ offices and retail locations were common. One was a startup called Rowan, which offered in-home ear piercing carried out by nurses as well as a safe earring subscription box.

Typically, coverage of Rowan’s services did not explain how Rowan’s staff nurses pierced the ears of its young clients. But an in-depth review published on January 2 2020 — after the post above began circulating on Facebook — included a photograph of one of Rowan’s nurses piercing a girl’s ears. In the photograph, the nurse was using a piercing gun, a detail reiterated by a commenter on a subscription box review of Rowan.

In the review, its writer notes the piercing tool is not spring-loaded:

Our nurse, Melissa, was sweet and patient with Ruby and her pal Amara, who wasn’t quite ready to get pierced. Nurse Melissa applied numbing cream to Ruby’s earlobes and carefully marked where the holes would go. When the big moment came, Melissa got out the piercing apparatus, which parents and kids will appreciate because it’s unassuming; no needle is visible. It’s not spring-loaded, like the piercing “guns” of the ’80s and ’90s; Rowan’s manual method is better for delicate little lobes. In fact, the company consulted with one of the top earlobe plastic surgeons in the United States to determine the best — and safest — way to pierce children’s ears.

A similar business in New York City called Clinical Ear Piercing seemed to feature piercing services similar to Rowan. A FAQ on Clinical Ear Piercing’s website explicitly described its equipment as a “gun”:

The piercing is performed using a medical ear piercing system used exclusively by medical practitioners. Earrings are prepackaged in sterile cassettes. You can be assured that anything that comes into direct contact with your skin is one-time use and disposed of after every client, therefore there is no chance of cross-contamination. We pierce babies using only a medical-grade piercing gun. Some older children can be pierced with a needle if they are able to sit still for the entire procedure.

Rachel Smith, nurse and owner of Clinical Ear Piercing, started the business in 2014. In an April 2017 piece in National Jeweler, Smith explained why she believed piercing guns were a safer option for young patients and earring-wearers:

Smith, a registered pediatric nurse, developed a reputation for expertly piercing newborn babies and children, so much so that in 2014 she founded a company dedicated to the service, Clinical Ear Piercing.

[…]

Smith uses a piercing gun rather than a needle because of the former’s stability, which is essential with infants in particular.

Debate over piercing guns appeared in a very extensive 2016 Racked piece about the history and culture of ear piercings. Smith was quoted, as was piercer Miro Hernandez:

This brings us to the other site of potential controversy in the piercing world, piercing guns. “We have a no-piercing-guns stance because of all the repercussions and potential damage they can cause, the questions about sterility and the quality of jewelry, all this stuff comes into play.” Rachel Smith of Clinical Ear Piercing says there is limited research on the difference between piercing with a gun or a needle, but that it is one of the most common questions she gets. She ultimately concluded that “there’s no difference. The tissue damage is virtually the same.”

Still, people like Hernandez take a hard line against the guns: “With a piercing gun, it’s a stud that’s basically loaded in a spring-load cartridge and it’s forced through, and it’s ripping and it’s causing trauma and damage. Whereas with a piercing needle you can make a really clean, simple single incision.” With the rare family doctor who still does piercings, they tend to use guns, though maybe a dermatologist — again, the rare one who actually bothers doing them — will opt for a needle.

Hernandez’s “hard line” stance on piercing guns was, in part, because they were spring-loaded. But the medical grade equipment favored by clinical ear piercers and doctors’ offices appeared to not be spring loaded, thereby not exerting the same force. The article noted that clinicians typically used piercing guns, but dermatologists sometimes opted to pierce with needles — a practice that did not sound especially well-suited for infants or small children.

Smith said she was asked most about claims that piercing guns were less safe than needles for earlobes, and she opined that there was “no difference” between the two methods when it specifically came to piercing ears. Smith also indicated there was “limited research” on the methods.

We attempted to contact Rowan, Blomdahl, and Clinical Ear Piercing to ask about why clinicians appeared to opt for guns more often than needles, but have not yet received responses. On occasion, clinicians using Blomdahl’s medical ear piercing system indicated [PDF] the piercing implement was “not a gun”:

No. Our instrument is a medical grade piercer. EVERY part of the instrument that comes in contact with the ears is disposable. The earrings are packaged singly and are completely encapsulated so there is no cross contamination whatsoever.

In contrast, reviewers typically described the system as “a piercing gun.” Based on the above information, the primary differences between retail piercing guns and medical setting piercing tools were single-use cassettes or implements, and whether the device was spring-loaded or not.

We did locate research contrasting the methods, published in 2008 in the Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. Researchers, writing that “literature suggests that a piercing gun, mainly used by jewellers to pierce the [ear lobe], may [cause] excessive cartilaginous damage,” noted that “no comparative histological studies [had] been performed” prior to their study to “evaluate the extent of damage to ear cartilage using different piercing techniques.” In the course of their research, they contrasted different piercing tools and piercing guns with needles, and described their methodology:

Twenty-two fresh human cadaver ears were pierced using two spring loaded piercing guns (Caflon and Blomdahl), one hand force system (Studex) and a piercing needle (16G i.v. catheter). Extent of damage to the perichondrium and cartilage was quantified using a transverse section along the pin tract and compared between the different methods.

They found “significant difference in the amount of injury between the different techniques was observed,” writing that the “pattern of injury was similar in all techniques, showing perichondrium stripped from the cartilage around the pin tract, with most damage present on the exit site.” The study’s conclusion noted assumptions in literature about the purported superiority of needles over piercing guns, finding that they appeared to be unfounded, but reiterating a focus on sterility and aftercare:

In contradiction with assumptions in the literature, all piercing methods give the same extent of damage to cartilage and perichondrium. Each method is expected to have the same risk for perichondritis, thus in the prevention of post-piercing perichondritis focus should be on other factors such as hygiene and after-care.

A Facebook post about “why you should say NO to piercing guns” was one of several popular pieces of circulating advice about ear piercing (lobes, not cartilage) and the purported “blunt-force trauma that’ll damage your ears” inherent. A rise in the popularity of body piercing undoubtedly influenced claims of that type, but the circulating post lacked citations and information from doctors and clinicians. Ear piercing stood apart from body piercing due to the former occurring in doctors’ offices (and mall kiosks) with regularity.

A spike in the popularity of piercing has not led most medical and clinical ear piercing procedures to transition to needle piercing, and companies like Clinical Ear Piercing cited stability and sterility as reasons for using a piercing implement sometimes described as a “gun” in its practice. The only relevant clinical research comparing ear piercing guns with needles demonstrated identical outcomes between the two, suggesting that it was at the very least not necessary to have infants and childrens’ ears pierced at body piercing studios. Doctors particularly seemed to favor the Blomdahl system, marketed exclusively to medical professionals and reliant on what was often described as a piercing gun. Companies staffed by nurses also used a “gun” to pierce ears, as did some dermatologists. It seemed a reasonable inference that if needle-only piercing was in any way a preferable procedure to a gun, doctors offices and clinical settings would have adopted it; they have not.

- Safe Piercing FAQ

- Safe Piercing FAQ/Guns

- AAP Announces its 1st Recommendations on Tattoos, Piercings and Body Modifications in Youth

- Embedded earrings: a complication of the ear-piercing gun

- The Risks of Infant Ear Piercing

- Ear Piercing For Kids: Safety Tips From a Pediatrician

- Ear Piercing

- Ear Piercing FAQ/Bee Well Pediatrics

- Ear Piercing For Children + Adults Alike

- Piercings: How to prevent complications

- WHAT KIDS SHOULD KNOW ABOUT GETTING PIERCING DONE SAFELY

- AAP Ear Piercing Guidelines

- American Academy of Pediatrics' Guidelines for Ear Piercing

- ROWAN EAR PIERCING

- Peak startup culture is here—and it draws blood

- This ear piercing startup wants to replace the mall experience

- Clinical Ear Piercing/Process

- This Line of Earrings Is Designed with Babies in Mind

- All Ears

- Medical Ear Piercing

- Our Blomdahl Ear Piercing Experience