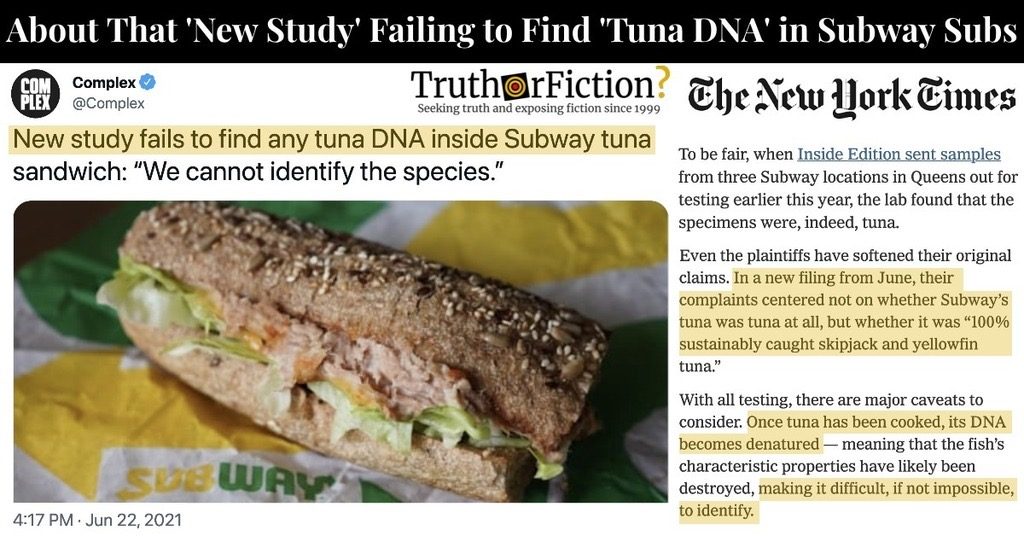

A viral June 22 2021 @Complex tweet contained a startling claim — that a “new study” utilizing DNA testing technology failed to find any tuna whatsoever in what was supposed to be a Subway tuna sandwich:

Alongside an image of a tuna sandwich sitting on a Subway wrapper, the tweet read:

New study fails to find any tuna DNA inside Subway tuna sandwich: “We cannot identify the species.”

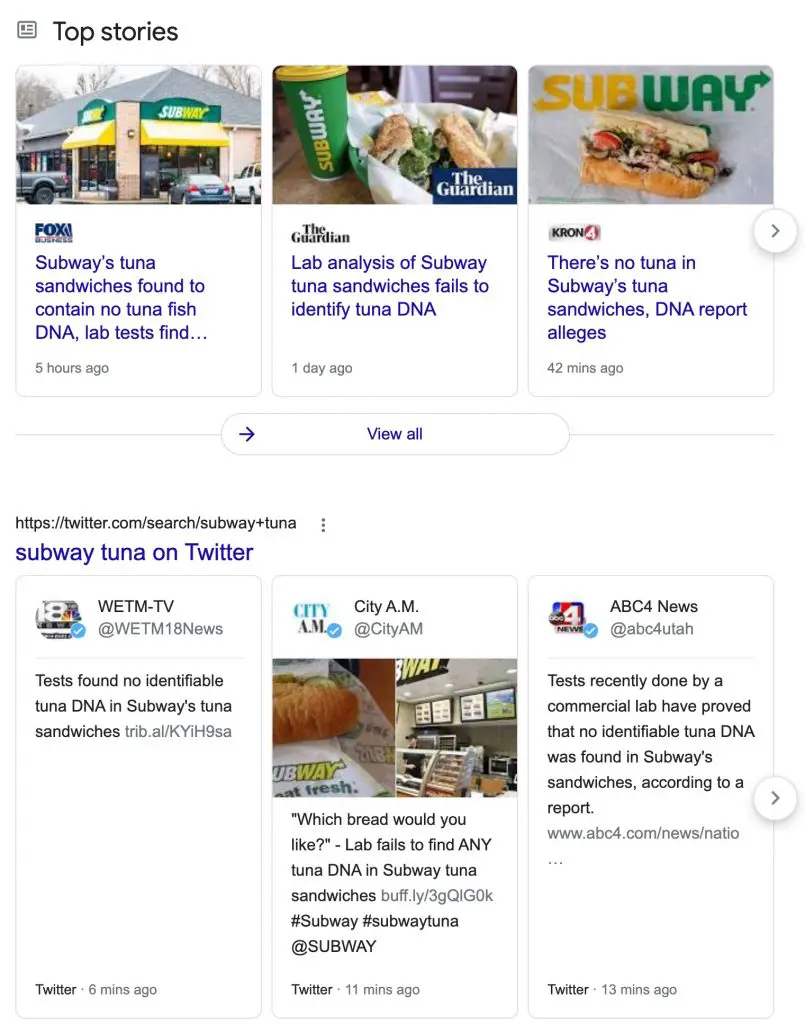

Linked in the tweet was a June 22 2021 Complex.com article, “A Lab Analysis Was Done to Determine Whether a Subway Tuna Sandwich Contained Tuna DNA.” Complex.com was not the only site pushing the claim — a search for “Subway tuna” turned up a number of contemporaneous links making similar assertions:

Google’s highlighted results included articles by Fox Business, The Guardian, and KRON4. Headlines blared:

- “Subway’s tuna sandwiches found to contain no tuna fish DNA, lab tests find …”;

- “Lab analysis of Subway tuna sandwiches fails to identify tuna DNA,” and;

- “There’s no tuna in Subway’s tuna sandwiches, DNA report alleges.”

Any person seeking additional information (particularly people who liked to eat Subway’s tuna sub) were likely to come across what appeared to be a news consensus that Subway’s tuna was something other than what could reasonably be considered tina. However, headlines contained flexible phrasing, like “DNA report alleges.”

Thousands shared the Complex.com tweet (and the individual results shown in the screenshot also likely gained traction), but those who clicked through and read the article might notice that it was not entirely reflective of the headline:

The study, commissioned by [New York Times], failed to not only identify tuna DNA, but the lab couldn’t even determine the origins of the fish in the provided sandwiches. “No amplifiable tuna DNA was present in the sample and so we obtained no amplification products from the DNA. Therefore, we cannot identify the species,” the results read.

“There’s two conclusions. One, it’s so heavily processed that whatever we could pull out, we couldn’t make an identification,” a lab spokesperson explained. “Or we got some and there’s just nothing there that’s tuna.” NYT spoke with a tuna expert who pointed out that the protein can be difficult to identify once it becomes broken down after being cooked.

A “lab spokesperson” originally quoted by the New York Times said that “two conclusions” included the tuna being “so heavily processed” that the identification process was affected, or that “nothing” there was tuna. But a separate “tuna expert” added that cooking can alter and break down the protein — presumably in a way that might affect or obscure the results of a DNA test.

On June 19 2021, the New York Times published “The Big Tuna Sandwich Mystery,” subtitled:

A lawsuit against America’s largest sandwich chain has raised questions about America’s most popular canned fish. We tried to answer one: Is Subway selling tuna?

Adjacent to the large headline was what appeared to be a cross-section of a tuna sub, frozen in a block of ice in a pink tray. The reporting began with some context about Subway’s tuna and its components:

[Canned tuna] can also be mysterious, questionable and scandalous. As The Washington Post reported in late January [2021], Subway — the world’s largest sandwich chain — is currently facing a class-action lawsuit in the state of California that claims its tuna sandwiches “are completely bereft of tuna as an ingredient.”

[…]

Subway, for its part, has categorically denied the allegations. “There simply is no truth to the allegations in the complaint that was filed in California,” a spokeswoman wrote in an email to The New York Times. “Subway delivers 100 percent cooked tuna to its restaurants, which is mixed with mayonnaise and used in freshly made sandwiches, wraps and salads that are served to and enjoyed by our guests.”

On January 29 2021, NBC News reported the filing of the California class action suit. A look over that reporting suggested that the initial suit perhaps was less viral because it was reported in a less sensational fashion:

A class action lawsuit filed [in January 2021] in California accuses Subway, the Connecticut-based fast food giant, of fraud and false advertising over the content of its tuna sandwiches, which the suit claims is an “entirely non-tuna based mixture that Defendants blended to resemble tuna and imitate its texture.”

Subway denied the allegations, telling NBC News in a statement it “delivers 100% cooked tuna to its restaurants, which is mixed with mayonnaise and used in freshly made sandwiches, wraps.”

“These baseless accusations threaten to damage our franchisees, small business owners who work tirelessly to uphold the high standards that Subway sets for all of its products, including its tuna,” Maggie Truax, Subway’s director of global PR, said in an emailed statement to NBC News. “Given the facts, the lawsuit constitutes a reckless and improper attack on Subway’s brand and goodwill, and on the livelihood of its California franchisees. Indeed, there is no basis in law or fact for the plaintiffs’ claims, which are frivolous and are being pursued without adequate investigation.”

Over the course of dozens of pages of the lawsuit, plaintiffs Karen Dhanowa and Nilima Amin claim they are seeking to represent a class of Subway customers who bought tuna sandwiches that they claim “entirely lack any trace of tuna as a component, let alone the main or predominant ingredient.”

The January 21 [2021] suit, filed in the U.S. District Court’s Northern District of California, claims that “independent testing has repeatedly affirmed” the plaintiffs’ claims, but does not mention where these tests were performed, when or by whom. There was no specific evidence to support these claims noted in the suit.

Dhanowa did not respond to NBC News requests for comment via phone call and text message. Amin did not respond to a NBC News emailed request for comment.

As of that January 2021 article, NBC News reported that two plaintiffs (Dhanowa and Amin) said in their lawsuit that “independent testing … repeatedly affirmed” their claims, adding that no “specific evidence to support these claims” appeared in the suit. Subsequently in that article, NBC News reported:

Noting that the plaintiffs consumed the sandwiches as recently as 2020, the suit also says the plaintiffs did not test the tuna in the sandwiches they actually ate.

On January 28 2021, Subwaydisseminated a press release responding to the filing, claiming that the class action suit was part of a known trend in which attorneys for the plaintiffs sought publicity by attacking well-known brands in the food industry:

There simply is no truth to the allegations in the complaint that was filed in California. Subway delivers 100% cooked tuna to its restaurants, which is mixed with mayonnaise and used in freshly made sandwiches, wraps and salads that are served to and enjoyed by our guests. The taste and quality of our tuna make it one of Subway’s most popular products and these baseless accusations threaten to damage our franchisees, small business owners who work tirelessly to uphold the high standards that Subway sets for all of its products, including its tuna. Given the facts, the lawsuit constitutes a reckless and improper attack on Subway’s brand and goodwill, and on the livelihood of its California franchisees. Indeed, there is no basis in law or fact for the plaintiffs’ claims, which are frivolous and are being pursued without adequate investigation.

Unfortunately, this lawsuit is part of a trend in which the named plaintiffs’ attorneys have been targeting the food industry in an effort to make a name for themselves in that space. Subway will vigorously defend itself against these and any other baseless efforts to mischaracterize and tarnish the high-quality products that Subway and its franchisees provide to their customers, in California and around the world, and intends to fight these claims through all available avenues if they are not immediately dismissed.

Justia.com hosted a docket for the suit (“Amin et al v. Subway Restaurants, Inc. et al“), and at least one lawyer for the plaintiff was named — Shalini Dogra. The most recent update provided was a continuance on March 10 2021.

Dogra was mentioned in a January 2021 Washington Post article (archived) about the suit, which addressed attorneys for the plaintiffs:

The plaintiffs in the current case are seeking compensatory and punitive damages as well as attorneys’ fees. They also want Subway to end its alleged practice of mislabeling its tuna sandwiches and surrender profits it earned from the practice. The plaintiffs have retained the services of the Lanier Law Firm, a firm with offices in several cities, including Los Angeles. Lanier has been involved in several high-profile lawsuits, including a case in which 22 women claimed Johnson & Johnson’s talcum powder products caused ovarian cancer. A jury awarded the plaintiffs $4.69 billion in damages in 2018.

One lingering matter in terms of reporting on the Subway tuna class action suit whether or not there was any truth to the claims. The June 2021 New York Times piece sought to independently determine whether the claims had merit:

… I procured more than 60 inches worth of Subway tuna sandwiches. I removed and froze the tuna meat, then shipped it across the country to a commercial food testing lab. I spent weeks chatting with tuna experts. I waited, and waited, until the lab results came back.

Immediately, the article described Subway tuna samples that had been presumably cooked, canned or frozen, sent to Subway franchises, made into tuna salad, and dispensed onto sub sandwiches. From that point, the samples were frozen in that state, shipped “across the country” to a lab, and tested — a long chain of events from the day on which the alleged tuna was allegedly caught.

The article also noted that a “handful” of prospective labs cited “technical limitations” in assessing the tuna samples — a possible hint that the chain of custody was perhaps a bit too long and weak at parts:

With all of that in mind, I began searching for a commercial lab that could test a sample of Subway’s product. A handful of them politely declined my inquiries, citing technical limitations and company policies that made my tuna ineligible for analysis. Eventually, I found myself on the phone with a spokesman for a lab that specializes in fish testing. He agreed to test the tuna but asked that the lab not be named in this article, as he did not want to jeopardize any opportunities to work directly with America’s largest sandwich chain.

For about $500, his lab could conduct a PCR test — which rapidly makes millions or billions of copies of a specific DNA sample — and try to tell me whether this substance included one of five different tuna species … Subway’s tuna and seafood sourcing statement says the chain only sells skipjack and yellowfin tuna — species that a lab would recognize as Katsuwonus pelamis and T. albacares.

A subsequent mention that “there are 15 species of nomadic saltwater fish that can be labeled ‘tuna'” seemed to be an important detail, if the test could determine whether the samples were one of five identifiable species of 15 total. It introduced variables depending on how prolific individual tuna varieties might be, and what would happen if the sample was one of the ten other species that can be labeled as tuna.

The author then disclosed the findings:

“No amplifiable tuna DNA was present in the sample and so we obtained no amplification products from the DNA,” the email read. “Therefore, we cannot identify the species.”

The spokesman from the lab offered a bit of analysis. “There’s two conclusions,” he said. “One, it’s so heavily processed that whatever we could pull out, we couldn’t make an identification. Or we got some and there’s just nothing there that’s tuna.” (Subway declined to comment on the lab results.)

To be fair, when Inside Edition sent samples from three Subway locations in Queens out for testing earlier this year, the lab found that the specimens were, indeed, tuna.

Even the plaintiffs have softened their original claims. In a new filing from June [2021], their complaints centered not on whether Subway’s tuna was tuna at all, but whether it was “100% sustainably caught skipjack and yellowfin tuna.”

With all testing, there are major caveats to consider. Once tuna has been cooked, its DNA becomes denatured — meaning that the fish’s characteristic properties have likely been destroyed, making it difficult, if not impossible, to identify.

That section included several details not mentioned in secondary reporting on the article:

- “No amplifiable tuna DNA was present in the sample”;

- A very similar experiment by Inside Edition involving samples from three Subway locations in Queens did result in an identification of tuna;

- “Even the plaintiffs” dialed back their claims from the suit’s initial filing in January 2021;

- In a June 2021 filing (not available via Justia.com), “their complaints centered not on whether Subway’s tuna was tuna at all, but whether it was ‘100% sustainably caught skipjack and yellowfin tuna,'” and;

- Cooked tuna’s DNA “becomes denatured,” “making it difficult, if not impossible, to identify.”

Contrasted with the dime-a-dozen headlines in June 2021 about the Subway tuna lawsuit, the caveats and nuances in the longer piece were important to consider. At the same time headlines based on the very same reporting blared that Subway’s tuna sandwiches were found to contain “no tuna fish DNA,” the source article provided a number of contextual details that placed that claim in jeopardy (while also jeopardizing clicks from fear-bating headlines).

Finally, Complex.com’s tweet claimed “a new study” found no tuna in Subway’s tuna sandwiches. That article was based on a New York Times article which was in no way a “study.”

In short, the New York Times elected to independently examine the claims in a class action lawsuit filed against Subway, claiming that “no tuna” was found in their tuna subs. A reporter froze and shipped samples of tuna sandwiches from LA-based Subways across the country for a story, after which a lab purportedly did not identify the samples as one of five (out of 15) species of tuna. The article also indicated that cooked tuna becomes “denatured,” making it “difficult, if not impossible” to identify as tuna.

- New study fails to find any tuna DNA inside Subway tuna sandwich: “We cannot identify the species.”

- A Lab Analysis Was Done to Determine Whether a Subway Tuna Sandwich Contained Tuna DNA

- The Big Tuna Sandwich Mystery

- Lawsuit claims Subway's tuna sandwiches contain no tuna

- Subway® Restaurants Serves 100% Wild-Caught Tuna and Fights Back Against Baseless Allegations

- Amin et al v. Subway Restaurants, Inc. et al

- Subway’s tuna is not tuna, but a ‘mixture of various concoctions,’ a lawsuit alleges