On November 10 2021, an Imgur user shared a screenshot of a 2014 tweet apparently from Sweden’s @sweden Twitter account — which looked like it was offering up advice on improving one’s fellatio skills:

The tweet was prefaced by the number seven, and Imgur u/WiredIn2Much titled their post “What is 1 [through] 6?” That tweet and a reply were depicted, and together they read:

Fact Check

Claim: A tweet from Sweden’s official @sweden account instructed fellow Swedes how to become more skilled at oral sex.

Description: An Imgur user shared a screenshot of a 2014 tweet reportedly from Sweden’s @sweden Twitter account, which looked like it was offering advice on improving one’s fellatio skills. This claim was investigated and it was found that the tweet, dated 2014, did exist on the @sweden timeline.

[@sweden] 7. My best advice for getting good at fellatio is to love cock. Once you got that covered geting good is a no-brainer.

[@TheMulletBird] Is there any context to this or did the entire country just think this advice needed shared?

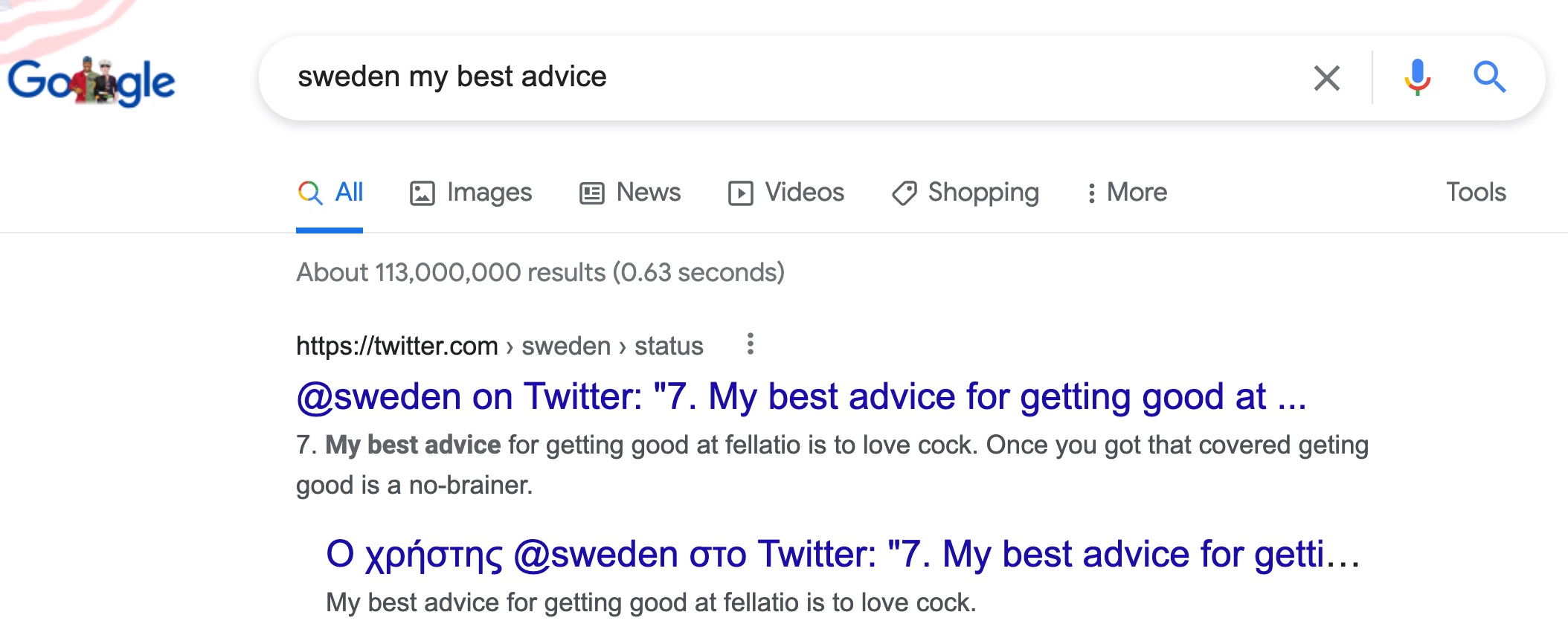

A Google search for “Sweden” and “my best advice” quickly returned an apparent link to a tweet that was not only real, but live as of November 11 2021:

Clicking through led to the tweet itself, on the verified @sweden timeline:

In addition to the tweet itself, @sweden replied to users baffled by it:

Establishing the veracity of the tweet was simple, but determining the context for it was slightly trickier. It appeared to be a piece of word-of-mouth internet lore, referenced in the comments of a September 2021 r/AskReddit post about good tweets:

TrendsMap indicated that the 2014 tweet got a boost on October 27 2021, via a viral tweet:

From there, the trail went fairly cold. A Google search for @Sweden and “best advice” in quotes returned just 25 results, primarily from sites like iFunny’s screenshots of the tweet. Searching for the more profane verbiage of the tweet returned articles that proffered a likely explanation for its content, but the actual tweet from 2014 was not mentioned.

On September 28 2018, Wired.com’s article “Say Goodbye to @sweden, the Last Good Thing on Twitter” reported that Sweden’s Twitter presence was the work of “random” Swedes, but that the account would no longer function in that capacity:

After seven years, the country’s grand experiment — turning its official Twitter account over to its citizens — comes to a close.

When @sweden began its grand experiment in 2011, Twitter had never seemed more full of possibilities. In New York, Twitter served as a digital bulletin board to organize protesters at Occupy Wall Street. In the Middle East, tweets served as the roots of the Arab Spring. Companies signed on to engage with customers; celebrities made accounts to grow their fanbases. And in Sweden, the government came up with a crazy idea: “How about we let any Swede — like, literally any of them — use the nation’s official Twitter account?”

That experiment is now about to end. On Sunday [September 30 2018], after seven years, @sweden will stop posting. And we’ll lose the last good thing on Twitter.

Wired.com explained how the @sweden account managed its content, and how the practice led to some unexpected musings from the country’s official Twitter feed:

The plan was simple: Every week, a new Swede would get the keys to @sweden, and the chance to share anything they wanted about Swedish life. (The only rule: nothing illegal.) The Swedish Institute partnered with a Stockholm-based creative agency to recruit some Twitter-literate Swedes, and found Jack Werner, a 22-year-old who had made his way into the Swedish media scene by writing about the internet. Werner agreed to be the account’s first “curator.”

[…]

Werner’s early tweets disrupted @sweden’s feed of travel tips and tourism information. He was candid, at times extremely personal, with a somewhat crude sense of humor. He tweeted about everything from dubstep to the death of his grandmother. When one follower asked how he coped with Swedish winters, he recommended masturbation. “In the first couple of days, I lost thousands of followers,” he says.

A somewhat disheartening article by The Verge in September 2018 (subtitled “Farewell, Masturbating Swede”) partly attributed the end of the experiment to increasing levels of online harassment and the comfort and safety of its curators. Tech site CNet also covered the end of @sweden’s years-long Twitter experiment, describing some of @sweden’s most memorable curators and recapping a minor conflict between a curator and former U.S. President Donald Trump in 2017:

Those in control of the account — residents of Sweden and Swedish citizens abroad — have been largely free to write whatever they want, as long as they don’t break the law, promote a commercial brand or appear to be a security threat.

[…]

In 2017, curator Max Karlsson decided to correct President Donald Trump when Trump suggested that a major security incident had taken place in Sweden.

“Hey Don, this is @Sweden speaking! It’s nice of you to care, really, but don’t fall for the hype. Facts: We’re ok!” Karlsson tweeted.

Determining the authenticity of @sweden’s “my best advice” tweet was straightforward, but the tweet itself was slightly decoupled from a broader context. Between 2011 and 2017, Sweden’s @sweden was managed by random Swedish citizens, free to tweet about any topic so long as it was law-abiding. The experiment led to a few controversies, and even some slightly bawdy discussions.. The experiment ended on September 30 2018, with one of its originators explaining that the initiative came to an end after the “internet and social media [had] since developed at an unprecedented rate,” adding that it was “time to move on.”

- "@Sweden 7. My best advice for getting good ... " | Imgur

- Sweden my best advice | Google search

- "@Sweden 7. My best advice for getting good ... " | Twitter

- "@Sweden 7. My best advice for getting good ... " | Twitter

- What's the funniest tweet you've ever seen? | r/AskReddit

- Thank you Sweden. | Twitter

- @sweden "best advice" | Google Search

- Say Goodbye to @sweden, the Last Good Thing on Twitter

- Sweden’s official Twitter account will no longer be run by random Swedes

- Sweden's Twitter account sheds citizen control after 7 years