On March 30 2020, a number of outlets reported that the Food and Drug Administration had given a limited go-ahead for the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in medical settings in the latest development in what has become a bizarrely (but not entirely unexpectedly) politicized debate over the drug.

That day, Newsweek reported that the FDA issued an “emergency use authorization” or EUA for the malaria drugs, in what is described as the first pharmaceutical therapy for COVID-19:

On [March 29 2020], the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a statement that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine could be prescribed to teens and adults with COVID-19 “as appropriate, when a clinical trial is not available or feasible,” after the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization. (EUA) That marked the first EUA for a drug related to COVID-19 in the U.S., according to the statement.

Currently, there are no specific drugs for COVID-19 which, as shown in the Statista graph below (accurate as of March 26 [2020]), has sickened over half a million people. According to Johns Hopkins University, over 720,000 cases have been confirmed, more than 34,000 people have died, and over 152,000 have recovered since the pandemic started in China late [2019].

Both pharmaceuticals were mentioned in early reporting on research into pharmaceutical therapies to treat COVID-19, subsequently becoming the basis of controversy during the coronavirus pandemic.

Where did the idea to use chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine come from?

In early February 2020, medical researchers in China proposed testing chloroquine as a possible novel coronavirus therapy in the journal Cell Research.

Researchers explained that one “efficient approach to drug discovery is to test whether the existing antiviral drugs are effective in treating related viral infection”; COVID-19 was not identified as a novel coronavirus until late 2019, and therefore no drugs already existed to treat this particular strain. The researchers cited similar efforts to identify appropriate existing pharmaceutical therapies for previously novel coronaviruses SARS and MERS, adding that those trials were met with mixed success:

The 2019-nCoV belongs to Betacoronavirus which also contains SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV (MERS-CoV). Several drugs, such as ribavirin, interferon, lopinavir-ritonavir, corticosteroids, have been used in patients with SARS or MERS, although the efficacy of some drugs remains controversial. In this study, we evaluated the antiviral efficiency of five FAD-approved drugs including ribavirin, penciclovir, nitazoxanide, nafamostat, chloroquine and two well-known broad-spectrum antiviral drugs remdesivir (GS-5734) and favipiravir (T-705) against a clinical isolate of 2019-nCoV in vitro.

Researchers noted that the testing conducted was “in vitro,” i.e., not in a living animal or person. They also stated that chloroquine was considered as a “potential broad-spectrum antiviral” medication, endeavoring to complete initial tests of its efficacy against in vitro samples of SARS-nCoV-2 (the particular coronavirus that causes COVID-19.)

In the journal article, researchers described chloroquine as a relatively old treatment (it has been used for more than 70 years), recently considered for use as a “broad-spectrum antiviral,” and that its secondary properties boosted the broader immune system. The researchers added that, if effective and expanded to trials in living organisms, chloroquine might work on two fronts — as an antiviral, and by bolstering immune response overall.

Finally, researchers speculated that chloroquine was an old and inexpensive drug generally well-tolerated and if found to be effective in trials, it was “potentially clinically applicable against” COVID-19:

Chloroquine, a widely-used anti-malarial and autoimmune disease drug, has recently been reported as a potential broad-spectrum antiviral drug. Chloroquine is known to block virus infection by increasing endosomal pH required for virus/cell fusion, as well as interfering with the glycosylation of cellular receptors of SARS-CoV. Our time-of-addition assay demonstrated that chloroquine functioned at both entry, and at post-entry stages of the 2019-nCoV infection in Vero E6 cells. Besides its antiviral activity, chloroquine has an immune-modulating activity, which may synergistically enhance its antiviral effect in vivo. Chloroquine is widely distributed in the whole body, including lung, after oral administration … Chloroquine is a cheap and a safe drug that has been used for more than 70 years and, therefore, it is potentially clinically applicable against the 2019-nCoV.

In that research, its authors believed in vitro trials showed potential. That potential, they explained, was for future testing, not for immediate use in humans:

Our findings reveal that remdesivir and chloroquine are highly effective in the control of 2019-nCoV infection in vitro. Since these compounds have been used in human patients with a safety track record and shown to be effective against various ailments, we suggest that they should be assessed in human patients suffering from the novel coronavirus disease.

They concluded by suggesting that research begin on human patients battling COVID-19. They did not recommend broad administration of the drug to patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

So the researchers proved chloroquine works to treat COVID-19?

No. They determined it showed promise in vitro — as in petri dishes or in cultures, rather than in human patients.

And the researchers said we should start dispensing chloroquine to people with COVID-19?

No. They suggested researchers begin testing its safety and efficacy in human subjects.

Did people start clamoring for more chloroquine research right away? Did Trump?

Not really, on both counts.

From early February through early March 2020, COVID-19 continued spreading, infecting people and killing many. Up to that point, United States President Donald Trump was upbeat on the matter of novel coronavirus. Per a critical March 15 2020 editorial in the New York Times:

[Trump] suggested on multiple occasions [in March 2020] that [COVID-19] was less serious than the flu. “We’re talking about a much smaller range” of deaths than from the flu, he said on March 2. “It’s very mild,” he told Hannity on March 4. On March 7, he said, “I’m not concerned at all.” On March 10, he promised: “It will go away. Just stay calm. It will go away.”

Then, on March 11 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic. That evening, Trump gave an official Oval Office address on the newly-declared coronavirus pandemic. You can read that speech here.

Did labeling COVID-19 a pandemic lead to increased interest in chloroquine as a treatment?

It doesn’t seem like it. For a few days after the WHO’s March 11 2020 declaration, coronavirus testing availability was a primary topic of news on COVID-19.

So when did COVID-19 become urgent? How did we get from a speech recommending hand-washing to nationwide lockdowns?

It seems pretty straightforward to identify the date worldwide response to the COVID-19 pandemic shifted: March 17 2020.

A day or two prior to that date, world leaders seemed dramatically change their statements about the novel coronavirus and its effects on daily life. That seems to be because on March 16 2020, researchers at Imperial College London published what is likely the most influential research into the COVID-19 pandemic to date:

On March 17 2020, we.com published an explainer about the research (above); the researchers’ findings seem to have directly led to the implementation of public policy such as quarantine and social distancing in the days that followed.

What happened after the Imperial College London research was published?

By March 20 2020, three days after it was reported in the news, millions of people all over the world entered a state of “lockdown.” In the U.S., states issued “shelter in place” or “stay at home” orders:

Illinois and New York state joined California on Friday in ordering all residents to stay in their homes unless they have vital reasons to go out, restricting the movement of more than 70 million Americans in the most sweeping measures undertaken yet in the U.S. to contain the coronavirus.

The states’ governors acted in a bid to fend off the kind of onslaught that has caused the health system in southern Europe to buckle. The lockdowns encompass the three biggest cities in America — New York, Los Angeles and Chicago — as well as No. 8 San Diego and No. 14 San Francisco.

“No, this is not life as usual,” New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said as the death toll in the U.S. topped 200, with at least 35 in his state. “Accept it and realize it and deal with it.”

So the report recommended lockdowns, quarantine, and social distancing. Did everyone just agree to go along with it?

For a time — a very, very short time.

By March 24 2020, President Trump kicked off calls to end social distancing measures and “return to work” via Twitter:

When did he say that?

March 24 2020.

Did he say anything else between the lockdowns on March 20 and March 24 2020?

As a matter of fact, he did. Among Trump’s tweets during that period were a retweet of this:

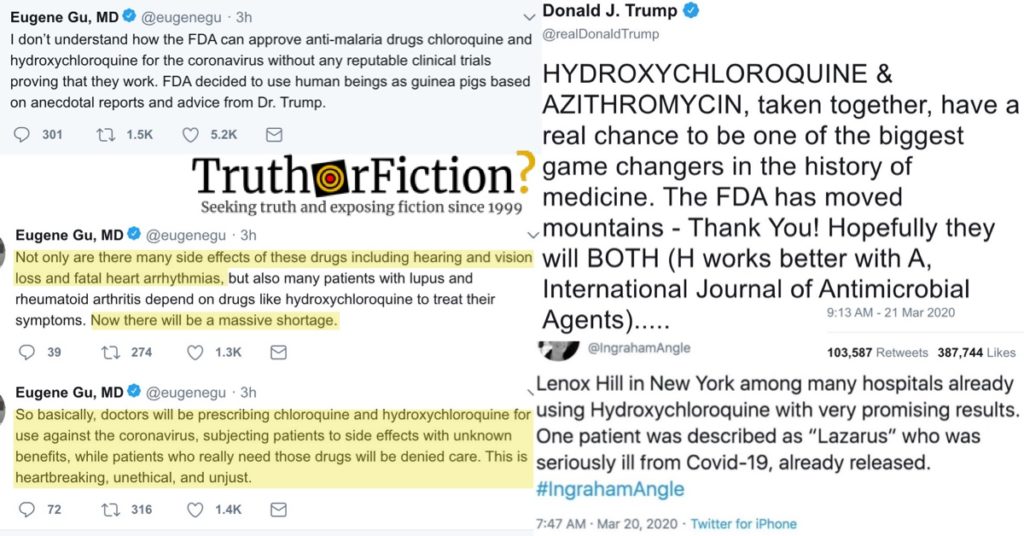

A direct tweet, which like the retweet was dated March 21 2020, also mentioned chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for COVID-19. In the tweet below, Trump mentioned azithromycin (an antibiotic also referred to as “Z-Paks“) and hydroxychloroquine “taken together.” He mentioned the combination again on March 24 2020:

So everyone read this Imperial College London report on March 17 2020, and several states went into lockdown on March 20 2020. Trump tweeted about this potential use of an existing drug on March 21 2020?

Correct. And he talked about it on March 19 2020:

What was the name of Imperial College London’s big-deal report anyway? What was it even about?

The report was titled: “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand.”

Its title alluded to the general premise of the research and researchers findings. Since COVID-19 is caused by a novel coronavirus, no drugs already existed to treat it; further, no vaccine is likely to be available until late 2021.

Consequently, only non-pharmaceutical approaches were available to combat it, because no drugs were yet developed to treat COVID-19. The basic crux of the report was likely best explained as: “Because we neither have drugs nor a vaccine to treat COVID-19, our only available avenues of treatment are measures such as extended quarantine and social distancing for a period of months or more.”

If we don’t have or can’t find any effective and safe drugs, what did researchers project were necessary measures to avoid millions of deaths?

A strategy called “suppression” was deemed the only chance of avoiding those deaths.

According the report, approaches that fell short of this would lead to a projected half a million deaths in the UK, and more than two million in the United States:

The major challenge of suppression is that this type of intensive intervention package – or something equivalently effective at reducing transmission – will need to be maintained until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more) – given that we predict that transmission will quickly rebound if interventions are relaxed.

[…]

In the (unlikely) absence of any control measures or spontaneous changes in individual behaviour, we would expect a peak in mortality (daily deaths) to occur after approximately 3 months. In such scenarios, given an estimated R0 of 2.4, we predict 81% of the GB and US populations would be infected over the course of the epidemic. Epidemic timings are approximate given the limitations of surveillance data in both countries: The epidemic is predicted to be broader in the US than in GB and to peak slightly later. This is due to the larger geographic scale of the US, resulting in more distinct localised epidemics across states than seen across GB. The higher peak in mortality in GB is due to the smaller size of the country and its older population compared with the US. In total, in an unmitigated epidemic, we would predict approximately 510,000 deaths in GB and 2.2 million in the US, not accounting for the potential negative effects of health systems being overwhelmed on mortality.

Wait, didn’t one of those researchers later admit that he was wrong?

No.

A pernicious bit of disinformation to that tune circulated on March 26 2020, published by the Daily Wire and amplified by bots, trolls, and useful idiots. It was later corrected, but spread widely anyway.

What does this have to do with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine?

It is possible that fast-tracking EUAs for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine were a direct result of a globally influential piece of research predicated on a lack of approved drugs to treat COVID-19.

But didn’t the FDA approve those drugs on March 28 2020?

Not exactly.

A letter from the Food and Drug Administration dated March 28 2020 indicated the drugs are not tested or approved for use to treat COVID-19. Approval for that use was authorized on an emergency basis, and the FDA said it has not approved the drugs as a safe treatment for COVID-19:

On February 4, 2020, pursuant to Section 564(b)(1)(C) of the Act, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determined that there is a public health emergency that has a significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad, and that involves the virus that causes COVID-19. Pursuant to Section 564 of the Act, and on the basis of such determination, the Secretary of HHS then declared that circumstances exist justifying the authorization of emergency use of drugs and biologics during the COVID-19 outbreak, pursuant to section 564 of the Act, subject to terms of any authorization issued under that section.

Chloroquine phosphate and hydroxychloroquine sulfate are not FDA-approved for treatment of COVID-19. Some versions of chloroquine phosphate are approved by FDA for other indications—for prophylaxis and acute attacks of certain strains of malaria and for the treatment of extraintestinal amebiasis, but the chloroquine phosphate drug product covered by this letter has not been approved. Several versions of hydroxychloroquine sulfate are approved by FDA for prophylaxis of and treatment of malaria, treatment of lupus erythematosus, and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The safety profile of these drugs has only been studied for FDA approved indications, not COVID-19.

In a March 29 2020 statement, the Department of Health and Human Services said that the emergency use authorization was based on anecdotal reports, but there had not yet been any clinical trials into its efficacy:

Anecdotal reports suggest that these drugs may offer some benefit in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Clinical trials are needed to provide scientific evidence that these treatments are effective.

Newsweek reported that a study published the week ending March 27 2020 showed that hydroxychloroquine demonstrated no benefit over other COVID-19 treatments.

Have any negative outcomes resulted from chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine in March 2020?

At least one fatality, although the couple sicked in that case used a non-pharmaceutical version of chloroquine that they found in their home:

The Banner Health hospital system, based in Phoenix, said March 23 [2020] that a man in his 60s died and his wife, also in her 60s, was in critical care after they had consumed a form of chloroquine phosphate used to clean fish tanks. The drug also has a number of adverse effects like nausea, changes in mood, and can cause drops in blood sugar. Incorrect doses can cause a coma, seizures or death.

What do scientists and medical experts think?

Although some are open to the idea, not all think that experimenting is a good strategy for treating COVID-19. Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, called the push premature:

“The president was talking about hope,” Anthony Fauci, director of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said diplomatically at one of the White House briefings where Trump praised the drugs’ potential.

Others are less diplomatic. Darren Dahly, a co-author of one of several critiques of the initial study and a principal statistician at the University College Cork School of Public Health, said it would be “egregious” to recommend treatments for millions of people based on such a small trial, regardless of its quality. “This is insane!” tweeted Gaetan Burgio, an Australian National University expert on drug resistance, noting what he sees as lapses in the 6-day trial, including inconsistent testing of virus levels in the patients.

To Dahly and others, only much larger, better studies such as one WHO has just started can show whether any optimism about the compounds is warranted. “The best way to know whether a medication for COVID-19 is effective is through a high-quality clinical trial,” says Joshua Sharfstein, a vice dean at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health and a former principal deputy Food and Drug Administration commissioner. “Efforts to widely distribute unproven treatments are misguided at best and dangerous at worst.”

On Twitter, Dr. Eugene Gu (a frequent and enthusiastic critic of Trump) provided two reasons the experiment might do more harm than good — side effects for one thing, and forcing those who take chloroquine for other medically necessary reasons to go without:

TL;DR, can I get a summary?

COVID-19, caused by a novel form of coronavirus, was so new that no drugs existed to treat it, and a vaccine was a long way off as of March 2020.

A globally-influential report on March 16 2020 addressed approaches to mitigating COVID-19 illnesses and deaths in the absence of any establisehd drugs to treat the virus. That vacuum led to intense interest in antimalarial drugs (chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine) due to initial in vitro testing as broad-spectrum antivirals.

In an absence of medication-based therapies for COVID-19, an emergency-use authorization for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine was issued by the FDA and HHS on or around March 28 2020. However, even those authorizations indicated that no clinical evidence existed supporting that usage, and their only evidence was anecdotal.

- FDA SAYS HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE AND CHLOROQUINE CAN BE USED TO TREAT CORONAVIRUS

- WHO declares the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic

- A Complete List of Trump’s Attempts to Play Down Coronavirus

- Read Trump's coronavirus Oval Office address

- Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro

- `Accept it': 3 states lock down 70 million against the virus

- Request for Emergency Use Authorization For Use of Chloroquine Phosphate or Hydroxychloroquine Sulfate Supplied From the Strategic National Stockpile for Treatment of 2019 Coronavirus Disease

- FACT SHEET FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) OF CHLOROQUINE PHOSPHATE SUPPLIED FROM THE STRATEGIC NATIONAL STOCKPILE FOR TREATMENT OF COVID-19 IN CERTAIN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

- There’s scant evidence for chloroquine so far as a COVID-19 drug. But there’s already a shortage