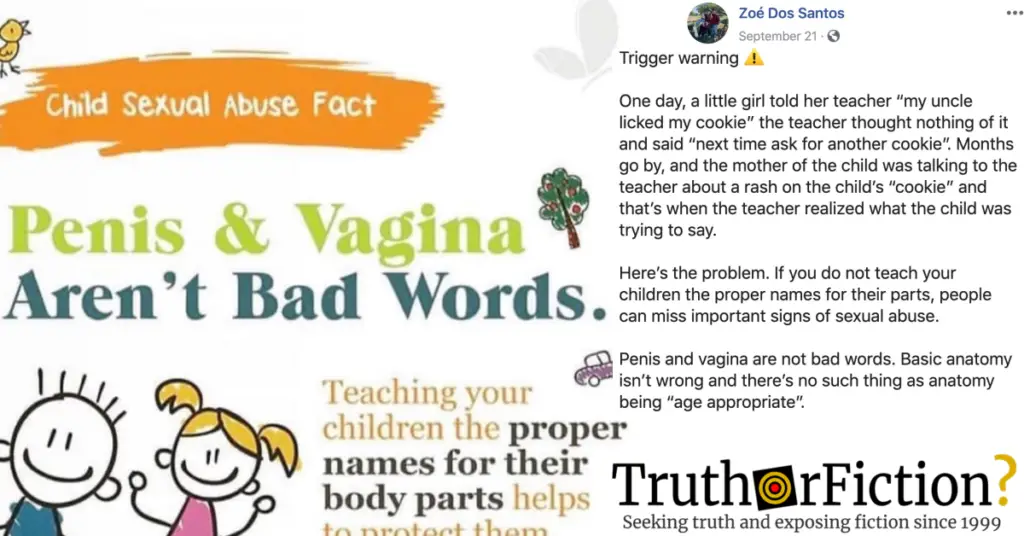

In September 2019, a Facebook user shared an image and a harrowing story about the purported sexual abuse of a toddler that went unreported for months because the young girl supposedly was not taught anatomically correct words:

Alongside a photograph of a childlike drawing (captioned “Penis & Vagina Aren’t Bad Words”), a poster named Zoé Dos Santos provided an anecdote involving a supposedly real little girl. The child reportedly endured “months” of sexual abuse at the hands of a relative, a scenario that it was heavily implied could have been prevented, had the girl only chosen an anatomically correct word:

Trigger warning ⚠️

One day, a little girl told her teacher “my uncle licked my cookie” the teacher thought nothing of it and said “next time ask for another cookie”. Months go by, and the mother of the child was talking to the teacher about a rash on the child’s “cookie” and that’s when the teacher realized what the child was trying to say.

Here’s the problem. If you do not teach your children the proper names for their parts, people can miss important signs of sexual abuse.

Penis and vagina are not bad words. Basic anatomy isn’t wrong and there’s no such thing as anatomy being “age appropriate”.

Dos Santos maintained that the problem evidenced by the anecdote was essentially that toddlers and young children not taught the words “penis” and “vagina” were at an increased risk of sexual abuse. Undoubtedly, interest in the claim itself was driven in part (probably large part) by the upsetting example the post contained.

The latter aspect was one that prompted curiosity — had a little girl genuinely attempted to report sexual abuse or molestation by telling a teacher that “my uncle licked my cookie,” only to be told to “ask for another cookie” next time? And had the misunderstanding only come to light months later, when a parent discussed the child’s diaper rash with the teacher? As an object lesson, the story really only “works” if the two discussions occurred across months, not days.

On its face, the story does not seem as though it was necessarily intended to be taken literally. The teacher heard, but did not disregard, the child’s seemingly meaningless assertion, then instantly recalled what seemed to be a highly forgettable exchange between herself and one of several students, but not until months later when the topic abruptly resurfaced — conveniently in a relevant context. It seemed just as likely had the teacher truly misunderstood the student’s complaint to be about a literal cookie, that it would have been one of hundreds of similarly benign statements made by a large group of toddlers every week.

To those familiar with urban legends as they spread on social media, the story very closely resembles classic examples of modern folklore. Described by the great folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand as “all those bizarre, whimsical, 99 percent apocryphal, yet believable stories that are ‘too good to be true,'” such tellings are often the vehicle of choice for tellers to drive home a perceived risk, danger, or other warning deemed too important to leave to a general advisory.

As a means of storytelling throughout recorded history, urban legends and moralistic folktales serve a specific purpose, illustrating a supposed risk in hopes the listener will take the moral of the story more seriously. Brunvand explains:

They are too odd, too coincidental, and too neatly plotted to be accepted as literal truth in every place where they are told and localized. Such stories deal with familiar everyday matters like travel, shopping, pets, babysitting, crime, accidents, sex, business, government, and so forth. Although the stories are phrased as if factual and are often attached to a particular locality, urban legends are actually migratory, and, like all folklore, they exist in variant versions. Typically, urban legends are attributed to a friend-of-a-friend, and often their narrative structure sets up some kind of puzzling situation that is resolved by a sudden plot twist, at which point the story ends abruptly. I emphasize story throughout this informal definition; I am not including plotless rumors, gossip, bits of misinformation, etc. Although these materials share some of the same features as urban legends, they are not technically the same genre, even though a few such borderline cases do merit mention in some of my entries.

Note that the structure of the anecdote attached to the warning about anatomical terms and small children. It dealt with at least three of the example topics (babysitting, crime, and sex), and like the form detailed, the tale ended abruptly after the “puzzling situation” and plot twist appeared. Once the teacher connected the girl’s seemingly throwaway remark about a “licked cookie,” no other information about what happened next is provided. The listener isn’t even afforded confirmation that the two conversations revealed the harrowing truth; that is only implied in this story.

As Wikipedia notes, “the teller of an urban legend may claim it happened to a friend (or to a friend of a friend), which serves to personalize, authenticate and enhance the power of the narrative and distances the teller,” continuing:

Many urban legends depict horrific crimes, contaminated foods, or other situations that would potentially affect many people. Anyone believing such stories might feel compelled to warn loved ones. On occasion, news organizations, school officials and even police departments have issued warnings concerning the latest threat.

Sexual molestation is among the most taboo and disturbing crimes against the very young, and when presented as a real example, those warned were indeed compelled to pass on the advisory. Hundreds of thousands of people in just a few weeks shared the story on, urging anyone with small children to protect their child by teaching them the correct words for their genitalia.

Another indicator the story may have been a known urban legend was its dispersal on the internet before the Facebook post went viral. In April 2018, a self-described “professional working with small children” claimed to have heard the story at a conference, passing it on as literal truth:

I attended a training on child sexual abuse, and in this training, they shared the story of a young girl 3-4 years old who told her teacher that her belly hurt because her uncle kept giving her cookies. That statement didn’t seem out of the ordinary to the teacher. Much later they discovered “cookies” is what the uncle called his penis. I can’t imagine how that teacher felt, but I’m sure the teacher would have done something or said something if the girl had said my stomach hurts because my uncle keeps giving me penis. The accuracy can make all the difference.

Lyba Spring, a sex educator in Toronto, referenced the anecdote in a 2015 news story:

Spring recounts a heartbreaking story told at a workshop by a woman who had been sexually abused as a child. Back then, the only word she knew for vulva was “cookie.” “When she tried to tell a teacher about how someone wanted her cookie, the teacher told her she had to share. It’s obvious that the consequence of that was that the abuse continued. She didn’t have the tools she needed to disclose.”

At the end of the piece, Spring observed that many parents feared their child losing their innocence, which unwittingly places them at much higher potential risk:

“I have encountered parents over the years who had a strong objection to naming parts. Some of them thought that it was ‘too young,'” Spring says. “They’re afraid that there’s somehow a direct link between naming the body parts and having sex. And they think that they can somehow maintain a child’s innocence by keeping them ignorant. There’s a difference between innocence and ignorance. Ignorance is dangerous.”

As in the Facebook iteration, the teacher in Spring’s parable verbally confirmed the initial understanding to the child victim — in that version, telling the little girl to “share” her cookie. And as the Facebook claim peaked in virality, Dos Santos spoke to a UK news site on October 9 2019, acknowledging that the anecdote was an “example” of how signs of abuse might appear:

[Dos Santos] explained to the M.E.N’s Manchester Family why she decided to write the post and said she’d used the ‘cookie’ reference as just one example of how these things can materialise.

“I work with the court systems attempting to get perpetrators charged and convicted. I shared it because in my culture, we have pet names for the body parts and after becoming a social worker and being in this line of work I’ve seen how the “pet names” can affect a criminal investigation, and affect investigation regarding any type of abuse.”

Closer to the end of the piece was input from the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) appeared. The advocacy group did not seem to think language was a massive barrier in uncovering child sex abuse:

When it comes to advice in the UK, the NSPCC stops short of telling parents which words to use, but emphasises the need for children to know that what’s inside their pants is private and for them to have the confidence to speak up when something is wrong.

[…]

“The most important thing is to have that conversation, and we would encourage parents to gauge their own child’s readiness and maturity when discussing these issues at home, in words they and their children are comfortable using.”

American advocacy group RAINN maintains a page titled “Warning Signs for Young Children.” Indicating that recognizing “the warning signs of child sexual abuse is often the first step to protecting a child that is in danger,” the group describes four “behavioral signs” and four “emotional signs” exhibited by young victims. None of those indicators involved using direct language (anatomical or not) to describe the abuse:

- Sexual behavior that is inappropriate for the child’s age

- Bedwetting or soiling the bed, if the child has already outgrown these behaviors

- Not wanting to be left alone with certain people or being afraid to be away from primary caregivers, especially if this is a new behavior

- Tries to avoid removing clothing to change or bathe

- Excessive talk about or knowledge of sexual topics

- Resuming behaviors that they had grown out of, such as thumbsucking

- Nightmares or fear of being alone at night

- Excessive worry or fearfulness

None of those eight signs ruled out direct statements made by the child, but neither did it seem likely victims of covert abuse would only or largely be helped by learning specific names for specific body parts. Doing so would not necessarily not help, but as many commenters pointed out, toddler speech development could lag or be slow to develop.

Another advocacy group warns of “new words” as a sign of sexual abuse, a symptom that might actually manifest as the child using words like “penis” and “vagina.” An Australian parenting site maintained a page similar to RAINN’s, but theirs advised against pressuring small children to use big or new words:

Stay alert if you think you are seeing signs such as the ones listed above. Watch what the child does, as well as what they say. Take written notes if you have any concerns.

You may like to have a calm conversation with the child, letting them know you have noticed that they don’t seem to be acting as they do normally (for example, they may seem sad or unwell). The child may tell you something about what they are experiencing. Listen, but don’t judge them and don’t pressure the child or say words you want them to say. It’s important that the words are theirs. Let them know that you are there to listen to them at any time.

It’s worthwhile to note that parental or caregiver recognition regarding the covert sexual abuse of children is a nuanced topic, with a number of signs and symptoms exhibited by child victims. Abuse is uncovered in a variety of ways, and child victims often exhibit seemingly unrelated symptoms such as aggression, regression, or bedwetting. And as WebMD explains, outward signs and symptoms of sexual abuse can often be confounding — including increased secrecy or aversion to things like undressing.

A final element of the story is that children often do mention abuse to primary caregivers when the abuser is known to them but not a parent or guardian. In the scenario described, it seemed likely at some point the child might have complained to her mother and father, who would have immediately understood the terminology used. The tale only works when the wording is not understood by an involved adult.

As presented, the tale speaks to a major and common fear — that someone close to us poses potential harm to our children. It also identifies one thing (words) that can serve as a bulwark against potential abuse. By spreading the warning, we hope that should such danger enter our lives, our knowledge will inoculate us and we will know exactly what steps to take in order to protect against such risk.

Like many viral Facebook posts, the “cookie” daycare story is both well-meaning and optimized for widespread sharing. We found instances of the same parable being relayed since at least 2015, spreading among social workers and at conferences. But the directive to teach all children anatomical terms didn’t seem to be as groundbreaking or vital as the post suggested. In terms of safety and awareness, there were a great many things parents and caregivers could know and do in order to protect children from abuse and better discern signs of abuse when spotted. In all the literature we reviewed, inability to accurately name body parts was not cited as a primary factor in failing to spot and deal with child sexual abuse.

- Encyclopedia Of Urban Legends

- Urban legend

- Urban legend

- Parents, It’s Not A Cookie…It’s A Vagina

- Why you should teach your kids correct names for genitals

- "It's not a cookie, it's a vagina" - social worker warns using pet names for body parts puts children at risk

- Warning Signs for Young Children

- Recognising signs of abuse in children

- Possible Signs of Child Abuse

- Tip Sheet: Warning Signs of Possible Sexual Abuse In A Child's Behaviors

- Signs of Sexual Abuse

- Signs of Childhood Sexual Abuse