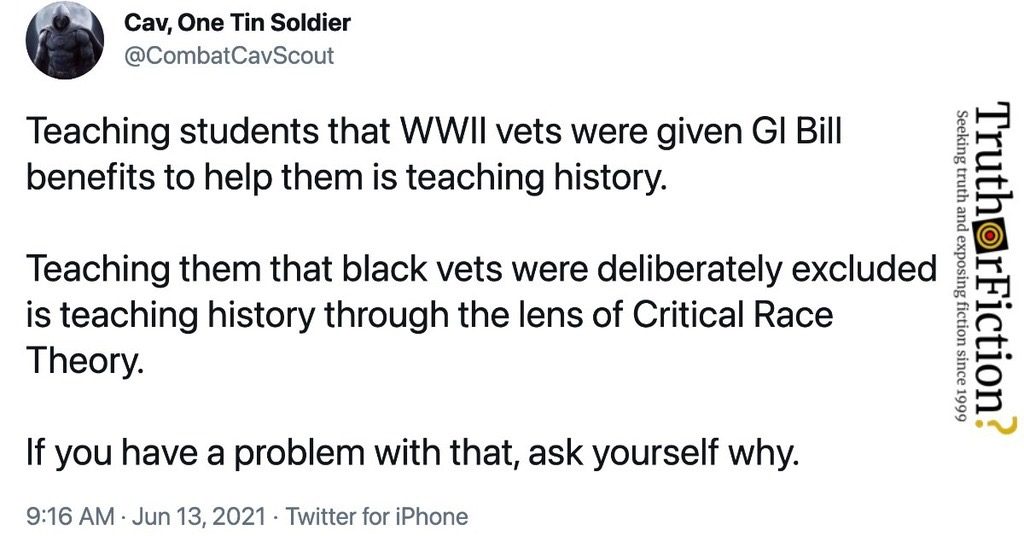

On June 18 2021, a commenter shared a Twitter screenshot to an education-related Facebook post about one of the provisions of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill:

The tweet said:

Teaching students that WWII vets were given GI Bill benefits to help them is teaching history.

Teaching them that black vets were deliberately excluded is teaching history through the lens of Critical Race Theory.

If you have a problem with that, ask yourself why.

In that tweet, @CombatCavScout addressed an ongoing weaponized disinformation campaign and ensuing discsussions about critical race theory. As an example, they said that the GI Bill’s benefits are well-known historically, but the exclusion of Black soldiers and veterans are not.

A June 2019 History.com piece about the GI Bill — published well before the current inauthentically organized campaign against various inaccurate definitions of critical race theory began — addresses how its benefits did not extend to Black soldiers.

History.com noted that although the GI Bill’s language “did not specifically exclude African-American veterans from its benefits, it was structured in a way that ultimately shut doors” for more than a million Black veterans who were purportedly eligible for its provisions:

When lawmakers began drafting the GI Bill in 1944, some Southern Democrats feared that returning Black veterans would use public sympathy for veterans to advocate against Jim Crow laws. To make sure the GI Bill largely benefited white people, the southern Democrats drew on tactics they had previously used to ensure that the New Deal helped as few Black people as possible … [President Franklin Delano] Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act into law on June 22, 1944, only weeks after the D-Day offensive began. It ushered into law sweeping benefits for veterans, including college tuition, low-cost home loans, and unemployment insurance.

[…]

Veterans who did qualify could not find facilities that delivered on the bill’s promise. Black veterans in a vocational training program at a segregated high school in Indianapolis were unable to participate in activities related to plumbing, electricity and printing because adequate equipment was only available to white students.

Simple intimidation kept others from enjoying GI Bill benefits. In 1947, for example, a crowd hurled rocks at Black veterans as they moved into a Chicago housing development. Thousands of Black veterans were attacked in the years following World War II and some were singled out and lynched.

As was often the case historically, the exclusion described was not always explicitly stated in the underlying legislation (the GI Bill, in this instance), or directly reflected in general records. Well-documented practices such as redlining (denying housing to homebuyers for reasons of ethnicity or beliefs) and racial disparaties in university admissions created a discernible barrier for Black veterans trying to access the bill’s benefits.

Historian Joseph Thompson wrote a piece for MilitaryTimes.com in November 2019, further explaining the racial disparities described in the tweet:

More than 2 million veterans flocked to college campuses throughout the country. But even as former service members entered college, not all of them accessed the bill’s benefits in the same way. That’s because white southern politicians designed the distribution of benefits under the GI Bill to uphold their segregationist beliefs.

So, while white veterans got into college with relative ease, black service members faced limited options and outright denial in their pursuit for educational advancement. This resulted in uneven outcomes of the GI Bill’s impact.

Thompson described how it played out in practice:

Black service members had a different kind of experience. The GI Bill’s race-neutral language had filled the 1 million African American veterans with hope that they, too, could take advantage of federal assistance.

Integrated universities and historically black colleges and universities – commonly known as HBCUs – welcomed black veterans and their federal dollars, which led to the growth of a new black middle class in the immediate postwar years.

Yet, the underfunding of HBCUs limited opportunities for these large numbers of black veterans. Schools like the Tuskegee Institute and Alcorn State lacked government investment in their infrastructure and simply could not accommodate an influx of so many students, whereas well-funded white institutions were more equipped to take in students.

So is Teaching Students About the GI Bill’s Disparity an Example of ‘Critical Race Theory’?

In a word, yes.

In more words, education site EdWeek.org attempted to unpack the Critical Race Theory discourse in May 2021, and used redlining (the same issue often tied to GI Bill disparity) as an example of critical race theory influencing education:

Critical race theory is an academic concept that is more than 40 years old. The core idea is that racism is a social construct, and that it is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.

The basic tenets of critical race theory, or CRT, emerged out of a framework for legal analysis in the late 1970s and early 1980s created by legal scholars Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado, among others.

A good example is when, in the 1930s, government officials literally drew lines around areas deemed poor financial risks, often explicitly due to the racial composition of inhabitants. Banks subsequently refused to offer mortgages to Black people in those areas.

[…]

Does critical race theory say all white people are racist? Isn’t that racist, too?

The theory says that racism is part of everyday life, so people—white or nonwhite—who don’t intend to be racist can nevertheless make choices that fuel racism.

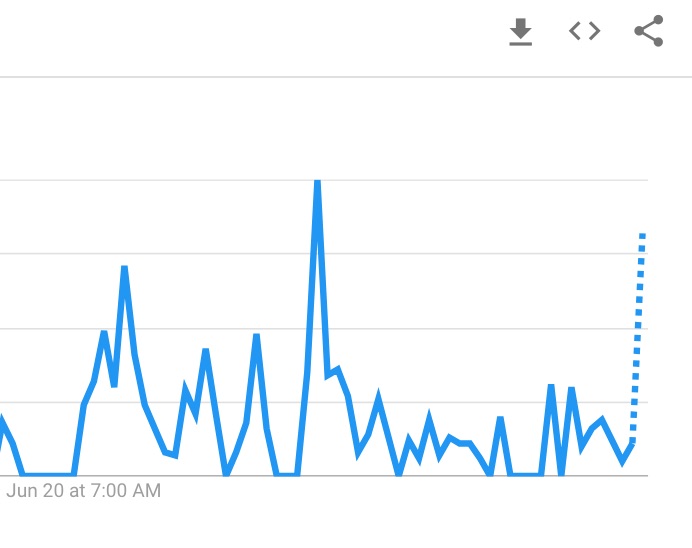

Google Trends data for the seven-day period ending on June 22 2021 demonstrated a spike in searches for “were Black soldiers eligible for GI bill,” underscoring the tweet’s basic claim that the GI Bill is part of history class — but the racial disparity aspect was news to many:

Summary

A June 2021 tweet asserted, “WWII vets were given GI Bill benefits to help them is teaching history,” and “teaching them that Black vets were deliberately excluded is teaching history through the lens of Critical Race Theory.” Both statements are accurate — historians addressed how Black soldiers and veterans did not receive the same benefits as white soldiers and veterans, and one such cause (redlining) was provided as a standard example of critical race theory’s influence on history lessons.

- Teaching students that WWII vets were given GI Bill benefits to help them is teaching history. Teaching them that black vets were deliberately excluded is teaching history through the lens of Critical Race Theory. If you have a problem with that, ask yourself why.

- Teaching students that WWII vets were given GI Bill benefits to help them is teaching history. Teaching them that black vets were deliberately excluded is teaching history through the lens of Critical Race Theory. If you have a problem with that, ask yourself why.

- Critical Race Theory | Tag

- G.I. Bill United States [1944]

- G.I. Bill

- G.I. Bill | Black Soldiers

- How the GI Bill's Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans

- The GI Bill should’ve been race neutral, politicos made sure it wasn’t

- Just what is critical race theory anyway?

- GI Bill | Black Soldiers