On February 6 2019, a Facebook post circulated claiming that “modern c-sections” were invented by midwives in Africa. The post had the hashtag #BlackHistoryMonth, and it said in its entirety:

Did you that modern C sections were invented by African women— centuries before they were standard elsewhere?

Midwives and surgeons living around Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria perfected the procedure hundreds of years ago. When a baby couldn’t be delivered vaginally, these healers sedated the laboring mother using large amounts of banana wine. They tied the mother to the bed for safety, sterilized a knife using heat, and made the incision, acting quickly as a team to prevent excessive blood loss or the accidental cutting of other organs. The combination of sterile, sharp equipment and sedation made the procedure surprisingly calm and comfortable for the mother.

After the baby was delivered, antiseptic tinctures and salves were used to clean the area and stitches were applied. Women rarely developed infections, shock, or excessive blood loss after a cesarean section and the most common problem reported was that it took longer for the mother’s milk to come in (an issue that was solved with friends and relatives who would nurse the baby instead).

In Uganda, C sections were normally performed by a team of male healers, but in Tanzania and DRC, they were typically done by female midwives.

The majority of women and babies survived this, and when questioned about it by European colonists in the mid-1800s, many people in Uganda and Tanzania indicated that the procedure had been performed routinely since time immemorial.

This was at a time when Europeans had only barely started to figure out that they should wash their hands before performing surgery, when nearly half of European and US women died in childbirth, and when nearly 100% of European women died if a C section was performed.

Detailed explanations of Ugandan C-sections were published globally in scholarly journals by the 1880s and helped the rest of the world learn how to save mothers and babies with minimal complications.

So if you’re one of the people who wouldn’t be alive today without a C-section, you have Ugandan surgeons and Tanzanian and Congolese midwives to thank for their contributions to medical science.

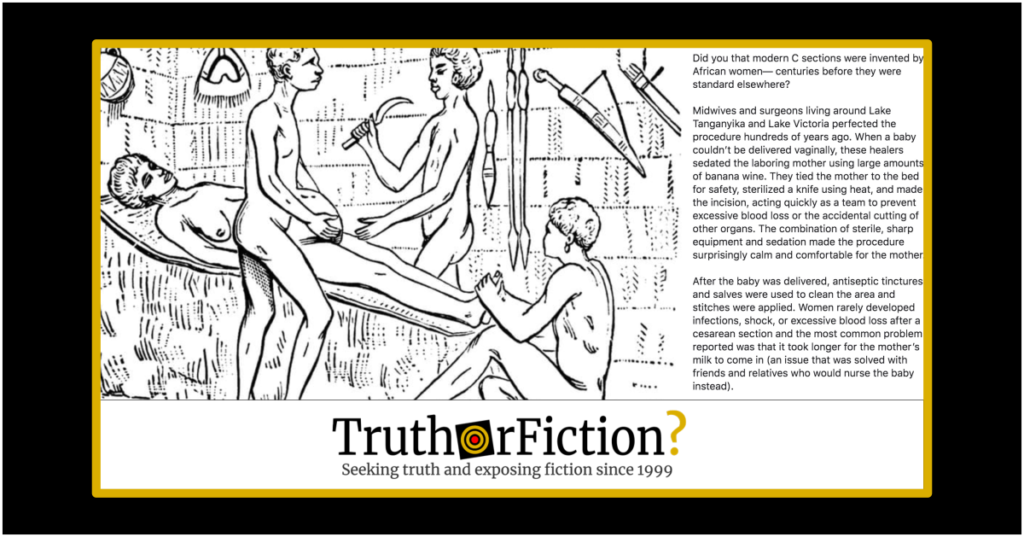

Attached to the post was the image seen above, an illustration of a medical procedure. The post made a number of assertions, some that were factual (the majority of mothers purportedly survived) and others that were more subjective (that “banana wine” enabled a “comfortable” experience). In the comments section of the post, the original posted provided a source for the claims — a 1999 article in a medical journal called Archives of Disease in Childhood — Fetal and Neonatal Edition.

The article featured the image, which was titled “Caesarean delivery in Uganda, 1879.” The article itself was historical and anecdotal in nature, consisting of background of and quotations from a lecture to the Edinburgh Obstetrical Society in January 1884 (“Notes on Labour in Central Africa.”) The lecturer, Robert Felkin, provided the “fascinating account” of a Caesarean delivery reproduced in the article. Its description was a bit less pastoral than the description in the Facebook post:

So far as I know, Uganda is the only country in Central Africa where abdominal section is practised with the hope of saving both mother and child. The operation is performed by men, and is sometimes successful; at any rate, one case came under my observation in which both survived. It was performed in 1879 at Kahura. The patient was a fine healthy-looking young woman of about twenty years of age. This was her first pregnancy … The woman lay upon an inclined bed, the head of which was placed against the side of the hut. She was liberally supplied with banana wine, and was in a state of semi-intoxication. She was perfectly naked. A band of mbuga or bark cloth fastened her thorax to the bed, another band of cloth fastened down her thighs, and a man held her ankles. Another man, standing on her right side, steadied her abdomen (fig 1). The operator stood, as I entered the hut, on her left side, holding his knife aloft with his right hand, and muttering an incantation. This being done, he washed his hands and the patient’s abdomen, first with banana wine and then with water. Then, having uttered a shrill cry, which was taken up by a small crowd assembled outside the hut, he proceeded to make a rapid cut in the middle line, commencing a little above the pubes, and ending just below the umbilicus. The whole abdominal wall and part of the uterine wall were severed by this incision, and the liquor amnii escaped; a few bleeding-points in the abdominal wall were touched with a red-hot iron by an assistant. The operator next rapidly finished the incision in the uterine wall; his assistant held the abdominal walls apart with both hands, and as soon as the uterine wall was divided he hooked it up also with two fingers. The child was next rapidly removed, and given to another assistant after the cord had been cut, and then the operator, dropping his knife, seized the contracting uterus with both hands and gave it a squeeze or two. He next put his right hand into the uterine cavity through the incision, and with two or three fingers dilated the cervix uteri from within outwards. He then cleared the uterus of clots and the placenta, which had by this time become detached, removing it through the abdominal wound. His assistant endeavoured, but not very successfully, to prevent the escape of the intestines through the wound. The red-hot iron was next used to check some further haemorrhage from the abdominal wound, but I noticed that it was very sparingly applied. All this time the chief “surgeon” was keeping up firm pressure on the uterus, which he continued to do till it was firmly contracted. No sutures were put into the uterine wall. The assistant who had held the abdominal walls now slipped his hands to each extremity of the wound, and a porous grass mat was placed over the wound and secured there. The bands which fastened the woman down were cut, and she was gently turned to the edge of the bed, and then over into the arms of assistants, so that the fluid in the abdominal cavity could drain away on to the floor. She was then replaced in her former position, and the mat having been removed, the edges of the wound, i.e. the peritoneum, were brought into close apposition, seven thin iron spikes, well polished, like acupressure needles, being used for the purpose, and fastened by string made from bark cloth. A paste prepared by chewing two different roots and spitting the pulp into a bowl was then thickly plastered over the wound, a banana leaf warmed over the fire being placed on the top of that, and, finally, a firm bandage of mbugu cloth completed the operation.

Until the pins were placed in position the patient had uttered no cry, and an hour after the operation she appeared to be quite comfortable. Her temperature, as far as I know, never rose above 99.6°F, except on the second night after the operation, when it was 101°F, her pulse being 108.

The child was placed to the breast two hours after the operation, but for ten days the woman had a very scanty supply of milk, and the child was mostly suckled by a friend. The wound was dressed on the third morning, and one pin was then removed. Three more were removed on the fifth day, and the rest on the sixth. At each dressing fresh pulp was applied, and a little pus which had formed was removed by a sponge formed of pulp. A firm bandage was applied after each dressing. Eleven days after the operation the wound was entirely healed, and the woman seemed quite comfortable. The uterine discharge was healthy. This was all I saw of the case, as I left on the eleventh day. The child had a slight wound on the right shoulder; this was dressed with pulp, and healed in four days.

During the 1884 lecture, Felkin recounted a number of circumstances he claimed to witness both during the procedure and after it. The patient was indeed tethered to a bed, and banana wine was administered for anesthetic purposes. He believed the patient to be “comfortable” through much of the procedure, owing to the fact that she “uttered no cry” until her wound was sutured. Felkin also observed the use of the anesthetic wine as an antiseptic along with water on both the practitioner’s hands and on the patient’s surgical site. Throughout the procedure, heated knives were used to cauterize the wound and prevent excess blood loss. In the days following the procedure, Felkin stated that the patient’s wound closed. He also observed that she developed a fever briefly, and that her milk production was delayed.

It appears that Felkin in part noted that the procedure was undertaken with the intent to preserve the mother’s life, suggesting perhaps that such an aim was less common in England in the same era.

The excerpted portion bore many similarities in procedural detail compared with the Facebook post. However, the source material quite clearly represented an anecdotal account provided by an individual in 1884 and reprinted without further research in 1999. Nothing in the article spoke to whether the procedure as described was common.

Another citation merely duplicated the original source:

In Western society women for the most part were barred from carrying out cesarean sections until the late nineteenth century, because they were largely denied admission to medical schools. The first recorded successful cesarean in the British Empire, however, was conducted by a woman. Sometime between 1815 and 1821, James Miranda Stuart Barry performed the operation while masquerading as a man and serving as a physician to the British army in South Africa.

While Barry applied Western surgical techniques, nineteenth-century travelers in Africa reported instances of indigenous people successfully carrying out the procedure with their own medical practices. In 1879, for example, one British traveller, R.W. Felkin, witnessed cesarean section performed by Ugandans. The healer used banana wine to semi-intoxicate the woman and to cleanse his hands and her abdomen prior to surgery. He used a midline incision and applied cautery to minimize hemorrhaging. He massaged the uterus to make it contract but did not suture it; the abdominal wound was pinned with iron needles and dressed with a paste prepared from roots. The patient recovered well, and Felkin concluded that this technique was well-developed and had clearly been employed for a long time. Similar reports come from Rwanda, where botanical preparations were also used to anesthetize the patient and promote wound healing.

That same resource provided context for the advent of c-sections in modern medicine:

Once anesthesia, antisepsis, and asepsis were firmly established obstetricians were able to concentrate on improving the techniques employed in cesarean section. As early as 1876, Italian professor Eduardo Porro had advocated hysterectomy in concurrence with cesareans to control uterine hemorrhage and prevent systemic infection. This enabled him to reduce the incidence of post-operative sepsis. But his mutilating elaboration on cesarean section was soon obviated by the employment of uterine sutures. In 1882, Max Saumlnger, of Leipzig made such a strong case for uterine sutures that surgeons began to change their practice. Saumlnger’s monograph was based largely on the experience of U.S. healers (surgeons and empirics) who had used internal sutures. The silver wire stitches he recommended were themselves new, having been developed by America’s premier nineteenth-century gynecologist J. Marion Sims. Sims had invented his sutures to treat the vaginal tears (fistulas) that resulted from traumatic childbirth.

[…]

As surgeons’ confidence in the outcome of their procedures increased, they turned their attention to other issues, including where to incise the uterus. Between 1880 and 1925, obstetricians experimented with transverse incisions in the lower segment of the uterus. This refinement reduced the risk of infection and of subsequent uterine rupture in pregnancy. A further modification — vaginal cesarean section — helped avoid peritonitis in patients who were already suffering from certain infections. The need for that form of section, however, was virtually eliminated in the post World War II period by the development of modern antibiotics.

As modern medicine developed to combat the infections that had until then so often proved fatal, c-sections became increasingly common. The introduction of antibiotics after World War II cemented their prevalence in labor and delivery.

In the Facebook post, the user referenced the late adoption of handwashing and sterilization in modern medicine as a difference in mortality rates associated with childbirth between central African countries and European ones. Although Felkin’s account described sterilization using water and banana wine, it didn’t go very deeply into the overall issue of antiseptic protocol in medical treatments.

The post alluded to but did not mention Ignaz Semmelweis, widely credited with identifying a connection between maternal mortality and handwashing in 1846. Semmelweis’ findings famously went unheeded, but charged into the medical mainstream two decades later via a seminal article in The Lancet:

… in 1867, Joseph Lister, a forty-year-old doctor, published an article in The Lancet that fundamentally changed medicine. “An Address on the Antiseptic System of Treatment in Surgery” was a description of a new way of doing operations that he first presented in Glasgow, Scotland, where he practiced medicine.

At that time, the “germ theory” of disease was just a theory. Lister’s innovation was simply to try to kill the germs.

Lister used a spray made of carbolic acid, on wounds, dressings and surgical tools. He also washed his hands. The acid killed the germs before they had a chance to cause infection, and the hand-washing kept new germs from being introduced.

Lister described the positive outcomes that this new way of doing surgery had for his patients: Wounded limbs “which would be unhesitatingly condemned to amputation” because of the probability of infection “may be retained with confidence of the best results”; abcesses could be drained; wounds could heal cleanly and hospitals were generally healthier places to be … Although British and American surgeons were irked by the “Scottish upstart,” according to Harvard University, “by 1875, sterilization of instruments and the scrubbing of hands were widely practiced.” Carbolic spray was exchanged for other antiseptics by 1885.

Overall, the Facebook post described Felkin’s observations accurately. However, we were unable to find more about the prevalence of c-sections in Africa in the 1800s in which both the mother and baby survived. Felkin definitely described the early adoption of groundbreaking techniques, and Semmelweis’ biography was long deemed an indicator of resistance to handwashing in the establishment of his time (and its effect on maternal mortality.) As an individual account, the post hewed closely to the single anecdotal account we located.