One day after the February 3 2020 Iowa caucuses — the first primary voting of all fifty American states — the hashtag #IowaCaucusDisaster remained at the top of Twitter’s “trending” charts after a confusing night with no clear, announced results.

Even before caucus-goers gathered in Iowa to participate, the lead-up to the event was, to say the least, unusual. One of the first unexpected occurrences involved a decision to withhold the results of a highly anticipated final poll because of an apparent irregularity involving presidential contender Pete Buttigieg:

The Des Moines Register poll, a closely watched indicator of the Iowa race, was canceled after at least one interviewer apparently omitted Pete Buttigieg’s name from the randomized list of candidates the surveyor read. The political website Axios reported that the reason for the error was that an interviewer increased the font size of the questionnaire on a computer screen, leaving the bottom choice invisible.

A prescient article published by The Atlantic on February 3 2020, prior to the start of the caucuses, predicted possible chaos:

BURLINGTON, Iowa—A crush of new Democratic voters, mobilized by a wave of anti-Trump energy, will arrive at their caucus precinct, and there will not be enough voter-registration forms. The lines will be long, and some Iowans, many of them elderly, will shiver in the cold for hours before getting inside. The caucus itself will be pandemonium: There won’t be enough preference cards for caucus-goers to write down their favorite presidential contenders. Voters will be incensed when they learn about the new realignment rules. There will be miscounts and recounts. And at the end of the night, once all the numbers have been crunched and recrunched, Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders will each claim victory.

This is Sandy Dockendorff’s nightmare scenario for tonight’s caucus. The 62-year-old former nurse, who is running a caucus in the small town of Danville, laid it all out for me over coffee [in late January 2020]. Her worst fears are unlikely to be realized. “The party has done everything it can to make sure that’s not the case,” she said. But the caucus is extremely complex, and rule changes threaten to make it even more bewildering for voters to navigate and complicated for the press to cover. The biggest fear: Democrats may not have a clear winner—a scenario that could further threaten Iowa’s imperiled first-in-the-nation position.

Alas, it seemed Dockendorff’s fears were more than realized as the night wore on. As results failed to appear, social media lit up with debate over what exactly was taking place in Iowa, leading to, among other things, memes satirizing the lack of reported results:

Just after 10PM Eastern time, the Iowa State Democratic Party stated it was doing “quality control” testing, thus delaying the results of the caucuses:

In a void where results had been anticipated, speculation and rumors predictably rushed in to take their place. A number of claims were popular on Twitter, many of which in whole or in part attempted to explain the mitigating factors in the Iowa caucus meltdown.

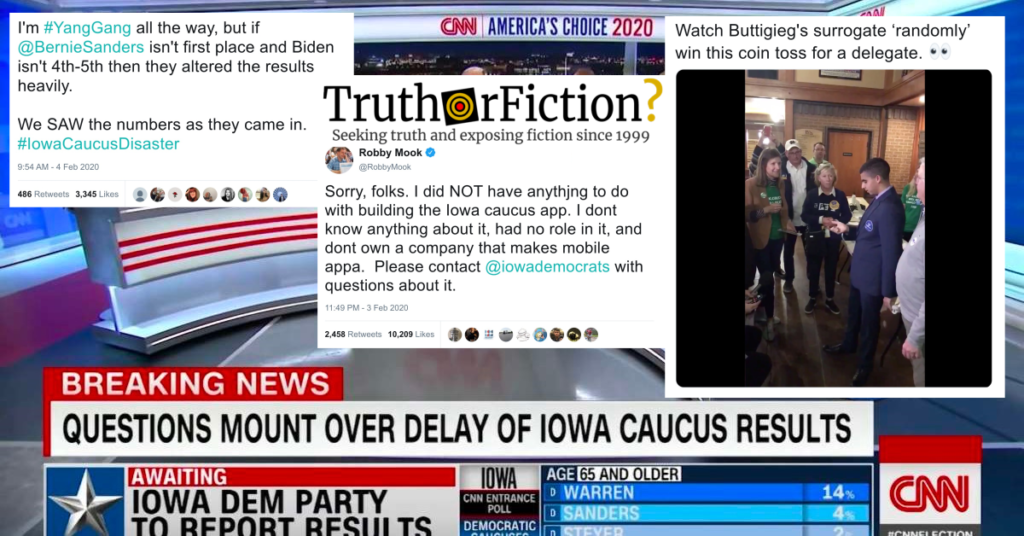

Rumor #1: Robby Mook, former campaign manager during Hillary Clinton’s unsuccessful 2016 presidential bid, designed an app used to limited efficacy during the Iowa caucuses.

Mook’s name emerged Monday night as the purported architect of an app being blamed for many of the problems with Iowa caucus reporting; the app developer was provided as Shadow, and a related company identified as ACRONYM:

Mook denied designing the app:

On January 29 2020, the Des Moines Register reported Mook and another former campaign manager had consulted with the app’s developers, not that either had a hand in developing it:

Both parties in Iowa and their app and web development vendors partnered [in fall 2018] with Harvard’s Defending Digital Democracy Project to develop strategies and systems to protect results and deal with any misinformation that’s reported on caucus night.

They worked with campaign experts Robby Mook and Matt Rhodes — as well as experts in cybersecurity, national security, technology and election administration — and simulated the different ways that things could go wrong on caucus night.

Mook, 2016 campaign manager for Hillary Clinton, and Rhodes, Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign manager, helped develop a public-service video to alert campaigns to the warning signs of hacking and misinformation.

It was released in 2018, days after a federal indictment detailed how Russian intelligence operatives hacked Clinton’s presidential campaign, the DNC and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in 2016.

Mook’s name did not appear in a separate February 4 2020 Des Moines Register item about Clinton campaign operatives and the app in play in Iowa, and the organization also reported that Nevada would not be using the app in its own caucus:

The smartphone application blamed in part for the ongoing delay in reporting results of the [February 3 2020] Iowa caucuses is linked with key Iowa and national Democrats associated with Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

The revelation came as the Nevada Democratic Party announced [February 4 2020] it would not be using the same app in its Feb. 22 [2020] caucuses, despite earlier reports to the contrary.

The app was issued by Jimmy Hickey of Shadow Inc., metadata of the program that the Des Moines Register analyzed Tuesday shows. Gerard Niemira and Krista Davis, who worked for Clinton’s 2016 campaign, co-founded Shadow.

Rumor #2: Iowa caucus results were delayed due to onerous reporting requirements instituted by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) on the request of Bernie Sanders supporters in 2016.

Another rumor spreading held that supporters of presidential candidate Bernie Sanders in 2016 were largely at fault for the Iowa caucuses debacle in 2020:

Tweets making that claim sometimes came with screenshots of a February 3 2020 Associated Press piece about changes to the caucus system:

Q: Why are Democrats making this change?

A: The new rules were mandated by the DNC as part of a package of changes sought by Bernie Sanders following his loss to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential primaries. The changes were designed to make the caucus system more transparent and to make sure that even the lowest-performing candidates get credit for all the votes they receive.

And it’s not just Iowa that is affected by the changes. The Nevada Democratic caucuses on Feb. 22 will also report three sets of results.

Without context, it looked as if those two conditions — Iowa’s delayed caucus results and Sanders’ objections to 2016 caucusing — were directly related. But a December 2017 Des Moines Register report about the changes as they unfolded provided a bit more context before the 2020 primaries were underway. It began by reporting that absentee Iowans would be able to participate in 2020:

Iowa’s first-in-the-nation Democratic presidential caucuses would break with decades of tradition in 2020 by allowing voters to cast absentee ballots and then releasing the raw total of votes won by each candidate.

A Democratic National Committee panel known as the Unity Reform Commission set those changes into motion during a meeting here [in December 2017], clearing the way for perhaps the most significant changes to the Iowa caucuses since they emerged as a key step in the presidential nominating process five decades ago … DNC Chairman Tom Perez called the caucus reforms “game-changing.”

“Obviously we want to make sure that if you’re a shift worker you can vote in a caucus,” Perez said. “We want to make sure a member of the military or someone else who’s been left out of the process — that you can vote, that you can make sure your franchise is exercised.”

The piece quoted Sanders 2016 operative Jeff Weaver on complaints about the 2016 caucus:

Commission member Jeff Weaver pointed to 2016 candidate Martin O’Malley, who campaigned heavily in Iowa and won a following but received 0.6 percent of the state delegate equivalents … The change forces Iowa, in effect, to release at least two different results: the traditional calculation of state delegate equivalents as well as a much more straightforward tally of votes.

Finally, the reforms centered on the controversial influence of DNC “superdelegates,” party-appointed individuals unbound by primary results with outsized influence on the final tallies:

In other business, the commission moved to scale back the influence of so-called “super-delegates” — the party leaders and insiders who were not bound to support a particular presidential candidate in previous national conventions.

In a series of recommendations, the commission sharply reduced the number of super-delegates who can back a candidate regardless of how that candidate performed in their home state’s caucus or primary. The move is a response to 2016 convention delegates and particularly supporters of Bernie Sanders who believed Hillary Clinton’s nomination was unfairly bolstered by super-delegates who were unaccountable to the will of voters in their states.

It is broadly true that supporters of Sanders (such as Weaver) as well as the DNC instituted reforms affecting the 2020 Iowa caucuses. But it was unclear whether those reforms — particularly ones involving superdelegates — had any direct effects on the Iowa caucus chaos.

Rumor #3: “Quality control.”

As mentioned above, Iowa’s official Democratic Party cited “quality control” as a cause for the delayed results, promising a 50 percent tally by 5PM on February 4 2020. It is true that the Democratic Party referenced “quality control,” but few details about what that meant exactly were available the morning after the Iowa caucuses:

The party said it was doing “quality control” on the results before releasing them out of “an abundance of caution.”

In a statement, the party said that 25% of precincts have reported results, but they have not publicly announced any numbers.

The delay was linked, in part, to issues with a new app being used by the Iowa Democratic Party to report precinct results, though the party denied that the app crashed.

The Iowa Democratic Party in a statement said, “We found inconsistencies in the reporting of three sets of results.”

At 1:14 PM EST on February 4 2020, NPR reported:

But as of Tuesday afternoon [February 4 2020], the state’s Democratic Party was still struggling to report the outcome of [the previous] night’s caucuses, blaming the delay on problems with that app. The party told campaign representatives it plans to release some results by 5 p.m. ET [on February 4 2020].

The party said it has determined “with certainty” that “the underlying data” via its new app “was sound.” In a statement Tuesday [February 4 2020], party chair Troy Price said the app was recording data accurately, but “it was reporting out only partial data” because of a “coding issue in the reporting system.”

NPR’s reporting also pointed out that the app and its late introduction to caucus chairs might be in part to blame for the chaos and confusion:

Multiple county chairs blamed the app for the delayed reporting of results.

Holly Christine Brown said she was only appointed [in late January 2020] as the Asian/Pacific Islander caucus chair for the Iowa Democratic Party and first saw the app on [the evening of January 31 2020].

“We were just given access to the app and told, ‘Play around in there a little bit,’ and that was about as much training as we got,” Brown told NPR’s Rachel Martin. “We were able to call in and ask questions, but there was no real training on the app.”

Brown said the problems with [February 3 2020] caucuses will “absolutely” increase calls to change Iowa’s system. “People are very upset about how this happened and how this played out,” she said.

Elesha Gayman, the Scott County Democratic chair, said the app was difficult to use for older and younger people alike.

“It was unique; it’s not something you can download in the app store,” she said. “You actually had to fill out a form. In addition to that, you got a series of PIN numbers. And so, yeah, there was a lot of layers and I think that absolutely mucked it up. Anecdotally, a few of the people I do know who used the app successfully were younger people. But I do know some young people that also had troubles, just so many layers.”

… But the app didn’t work for Des Moines County Democratic Party Co-Chairman Tom Courtney.

“Things didn’t work out right,” said Courtney, who said he tried to call in the results for several hours but couldn’t get through because the number was “constantly busy.”

NPR also echoed reporting about Nevada Democratic Party officials swearing off use of the app for their February 22 2020 caucuses:

“NV Dems can confidently say that what happened in the Iowa caucus last night will not happen in Nevada on February 22nd [2020],” the party said in a statement. “We will not be employing the same app or vendor used in the Iowa caucus. We had already developed a series of backups and redundant reporting systems, and are currently evaluating the best path forward.”

Rumor #3: Unfair coin flips or coin tosses.

A contentious element of the 2016 Iowa caucuses involved the purported use of coin flips to award delegates, a factor witnesses inevitably claimed was unfair. A number of Iowa coin flip rumors circulated on Twitter, but as was the case in 2016, their claims were impossible to either verify or debunk:

Myriad rumors about the delay continued spreading on social media the day after the Iowa caucuses. Use of a new app called Shadow was blamed by many caucus chairs for the difficulties, and Iowa’s Democratic Party cited only an “abundance of caution” regarding “quality control” for the delays. Related rumors about coin flips or coin tosses used to award delegates also circulated widely on social media, but without firm results or numbers, it remained difficult to draw any conclusions about the array of speculative claims regarding chaos at Iowa’s caucuses in 2020.

- Conspiracy theories swirl over canceled Iowa poll, pushed by Sanders and Yang supporters

- The Iowa Caucus Could Go Very Wrong

- Unprecedented cybersecurity measures being taken to safeguard Iowa caucus results

- People are wrongly making Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager the villain of the Iowa caucus (updated)

- AP Explains: New rules could muddle results of Iowa caucuses

- Clinton campaign veterans linked with app that contributed to caucus chaos

- The Iowa caucus results are set to be released late Tuesday after massive reporting delays sparked widespread chaos

- What We Know About The App That Delayed Iowa's Caucus Results