In December 2018, claims that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had once deemed the holiday classic film It’s a Wonderful Life to be “communist propaganda” circulated on various social media sites:

Fun Fact: Months after It’s A Wonderful Life was released, The FBI thought it was communist propaganda due to the wealthy banker being the villain.

— Tim Miller (@TimMiller2011) December 26, 2018

Variations of the rumor mentioned author and Objectivist icon Ayn Rand as central to the claim:

Horrible Libertarian Ayn Rand was part of the team who tried to condemn “It’s a Wonderful Life” as dangerous Communist propaganda:

…when [“It’s a… https://t.co/yr3mac1ot1

— London Aftr Midnight (@LAMofficial) December 25, 2018

One linked article from 2013 explained:

It’s a Wonderful Life is a staple of the holiday season in the United States, but it was once considered un-American by the government.

From the film’s release in 1946 until 1956, it was listed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as suspected Communist propaganda. Mr. Potter, the villainous banker who nearly drives George Bailey to financial ruin and suicide, “represented a rather obvious attempt to discredit bankers by casting Lionel Barrymore as ‘scrooge-type’ so that he would be the most hated man in the picture,” according to an FBI report (pdf, pg. 14) in 1947.

The report called it “a common trick used by Communists.”

Adding that “the FBI’s analysis … concluded that the film ‘deliberately maligned the upper class,'” the piece continued:

In 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee held a hearing on the matter. The film critic John Charles Moffitt defended the film: “I think Mr. Capra’s picture, though it had a banker as villain, could not be properly called a Communist picture. It showed that the power of money can be used oppressively, and it can be used benevolently.”

This contextual information about It’s a Wonderful Life is periodically rediscovered by readers. This happens during the Internet age with some regularity. For example, during the 2016 presidential campaign, a striking 1964 political ad (the “Confessions of a Republican” video) recirculated; in social media debates about refugees, historical claims about Anne Frank and Dr. Seuss also spread prominently on social sharing sites.

An article published on WiseBread in 2006 about the film contained similar details:

FBI Considered “It’s A Wonderful Life” Communist Propaganda

I love It’s a Wonderful Life because it teaches us that family, friendship, and virtue are the true definitions of wealth.

In 1947, however, the FBI considered this anti-consumerist message as subversive Communist propaganda.

According to Professor John Noakes of Franklin and Marshall College, the FBI thought Life smeared American values such as wealth and free enterprise while glorifying anti-American values such as the triumph of the common man.

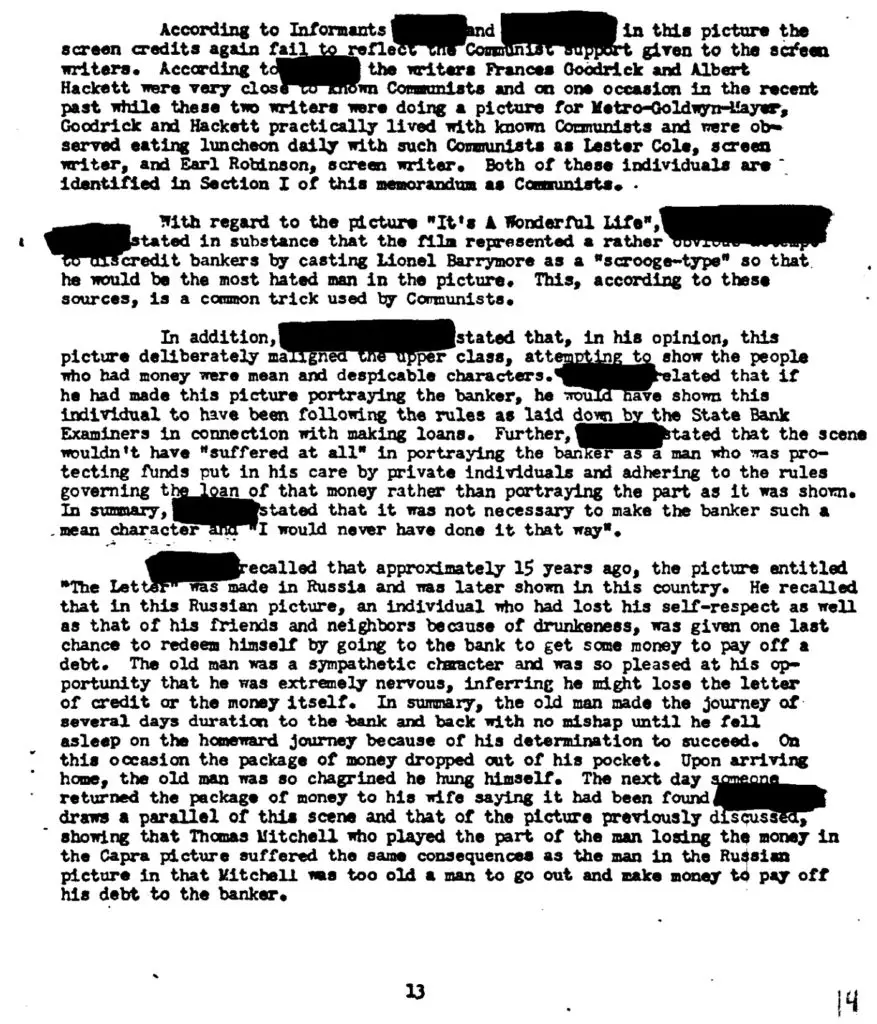

Both The Atlantic and WiseBread included a link [PDF] to a scanned document about communist infiltration in the motion picture industry of the 1940s:

This memo (titled “COMMUNIST INFILTRATION OF THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY”) listed It’s a Wonderful Life alongside other films being judged for how “anti-American” (or not) they were perceived to be at the time:

With regard to the picture “It’s a Wonderful Life”, [redacted] stated in substance that the film represented rather obvious attempts to discredit bankers by casting Lionel Barrymore as a “scrooge-type” so that he would be the most hated man in the picture. This, according to these sources, is a common trick used by Communists.

In addition, [redacted] stated that, in his opinion, this picture deliberately maligned the upper class, attempting to show the people who had money were mean and despicable characters. [redacted] related that if he made this picture portraying the banker, he would have shown this individual to have been following the rules as laid down by the State Bank Examiner in connection with making loans. Further, [redacted] stated that the scene wouldn’t have “suffered at all” in portraying the banker as a man who was protecting funds put in his care by private individuals and adhering to the rules governing the loan of that money rather than portraying the part as it was shown. In summary, [redacted] stated that it was not necessary to make the banker such a mean character and “I would never have done it that way.”

A 2014 article from the website Open Culture (Ayn Rand Helped the FBI Identify It’s A Wonderful Life as Communist Propaganda) seemed to be in heavier circulation in December 2018. That piece linked Rand and the FBI’s interest in that specific film, but the context in the piece described an influence that was markedly less direct:

If you wanted to know what life was really like in the Cold War Soviet Union, you might take the word of an émigré Russian writer. You might even take the word of Ayn Rand, as the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) did during the Red Scare, though Rand had not lived in her native country since 1926. Nonetheless, as you can see above, she testified with confidence about the daily lives of post-war Soviet citizens. Rand also testified, with equal confidence, about the nefarious influence of Communist writers and directors in her adopted home of Hollywood, where she had more recent experience working in the film industry.

The 1947 HUAC hearings, writes the blog Aphelis, led to “the systematic blacklisting of Hollywood artists.” Among the witnesses deemed “friendly” to capitalism were Gary Cooper, Walt Disney, and Ayn Rand. Prior to her testimony, the FBI had consulted Rand for an enormous, 13,533-page report entitled “Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry” (find it online here), which quoted from a pamphlet published by her group[.]

That article referenced the redacted identities in the FBI documents, observing that while they could not say for certain, it was “reasonable to assume” that many of those redacted sources in the FBI documents “were associates of Rand.” It continued, noting that Rand’s perspective appeared to apply to the motion picture industry as a whole — and that her specific, on-record commentary involved other films:

In any case, Rand — in vogue after the success of her novel The Fountainhead—appeared before HUAC and re-iterated many of the general claims made in the report. During her testimony, she focused on a 1944 film called Song of Russia (you can hear her mention it briefly in the short clip at the top). She chiefly critiques the film for its idealized portrait of life in the Soviet Union, hence her enumeration of the many evils of actual life there.

Most examinations referenced a 1998 Film History article from which the notion appeared to originate. That article indicated that the Los Angeles FBI field office considered the film potentially “subversive,” but not that it had been specifically confirmed as “communist propaganda”:

In a report dated 7 August 1947, however, the Los Angeles field office finally proved a review of the content of eight films in general release during 1947, including It’s a Wonderful Life. To determine which films were subversive and to identify the actual subversive content, the Los Angeles field office utilised a report issued by a self-assembled ‘group of motion pictures writers, producers and directors who had been alerted to the common menace within the industry’. This ad-hoc group identified three categories of ‘common devices used to turn non-political pictures into carriers of political propaganda’. Applying these ‘common devices’ to It’s a Wonderful Life, the Los Angeles field office concluded that in at least two ways the film served as a ‘carrier of political propaganda’.

Discovering the FBI’s purported interest in It’s a Wonderful Life as communist propaganda seems to be on the verge of becoming a Christmas tradition in its own right. Rand seemed to get attached to annual circulations of the claim with a comprehensive 2013 blog post that described It’s a Wonderful Life‘s appearance in the memo alongside a (separate) piece about a (separate) memo detailing the author’s cooperation with efforts to identify subversive themes in media in Hollywood during the late 1940s.

The notion the FBI deemed It’s a Wonderful Life “communist propaganda” appears to have germinated in a 1998 article detailing a broader effort to identify subversive content in Hollywood during Communist scares in the late 1940s. As that research was rediscovered each year — seemingly one step further removed from its source — the nuance of the claim steadily fell away. By 2018, it was a “fun fact” that the FBI declared a beloved Christmas film “communist propaganda.”

While it is certainly interesting that the film was on the FBI’s anti-American activities radar, the rumor’s basis lay largely in the opinions of non-law enforcement personnel transcribed into a broad-ranging memo in 1947. Unless further information remains classified or unreleased, we found nothing to indicate the Bureau’s interest spanned further than the one-page mention it received among other movies of the era.

- The FBI Considered 'It's a Wonderful Life' to Be Communist Propaganda

- The Complicated Relevance of Dr. Seuss's Political Cartoons

- Anne Frank and her family were also denied entry as refugees to the U.S.

- Confessions of a Republican

- FBI Considered "It's A Wonderful Life" Communist Propaganda

- Communist infiltration - motion picture industry (compic) (excerpts)

- Ayn Rand Helped the FBI Identify It’s A Wonderful Life as Communist Propaganda

- ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ alleged Communist propaganda: the FBI files and HUAC hearings

- Bankers and Common Men in Bedford Falls: How the FBI Determined That "It's a Wonderful Life" Was a Subversive Movie

- ‘It’s A Wonderful Life’ Had an FBI File, and It’s Kind of Hilarious