In August 2014, the Federal Commmunications Commission (FCC) began an investigation into the discovery of seventeen “interceptor” structures designed to resemble actual cell phone towers.

Concerns over “interceptors,” also known as “IMSI catchers,” began following a report six months earlier in Newsweek about the proliferation of these types of devices, which targeted a particular signal known as the International Mobile Subscriber Identity, emitted by any kind of device that communicates with a cell phone tower — not just cell phones, but tablet devices and smartphones.

The feds don’t want U.S. citizens to know about the technology, critics say, because they are shielding their use of similar devices, the most prominent of which is the StingRay.

…

What StingRay (manufactured by Florida-based Harris Corp.) and its competitors do is act like a cellphone tower, drawing the unique IMSI signals into their grasp. Once the device is locked onto a signal, the quarry’s data is ripe for the plucking. Major targets include people working for U.S. national security agencies, defense contractors and officials, including members of such congressional panels as the armed services and intelligence committees.

“This type of technology has been used in the past by foreign intelligence agencies here and abroad to target Americans, both [in the] U.S. government and corporations,” former FBI deputy director Tim Murphy tells Newsweek. “There’s no doubt in my mind that they’re using it.”

As Popular Science magazine reported later that year, several “IMSI catchers” were also identified by Les Goldsmith, the chief executive officer of ESDA America:

Interceptors look to a typical phone like an ordinary tower. Once the phone connects with the interceptor, a variety of “over-the-air” attacks become possible, from eavesdropping on calls and texts to pushing spyware to the device.

“Interceptor use in the U.S. is much higher than people had anticipated,” Goldsmith says. “One of our customers took a road trip from Florida to North Carolina and he found 8 different interceptors on that trip. We even found one [in the vicinity of] South Point Casino in Las Vegas.”

Goldsmith said that the fake towers were discovered through the use of his company’s own device, the GSMK CryptoPhone 500. As the MIT Technology Review reported, the GSMK operates using a tweaked version of Google’s Android operating system. It can only be used to call other cryptophones.

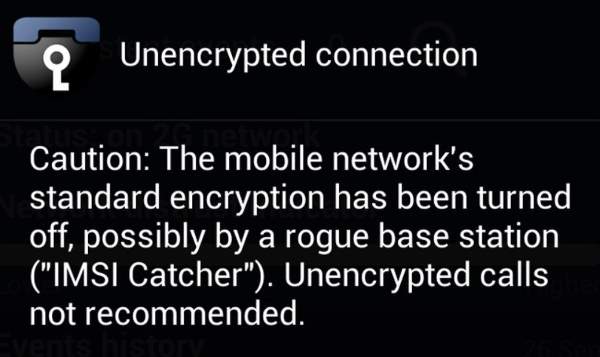

Unlike actual cell phone towers, interceptors (identified by Goldsmith’s company as “rogue base stations”) are outfitted with software that enables them to access antiquated cellular networks and to bypass onboard encryption systems. Most cell phones can’t distinguish interceptor towers from ordinary towers — which leaves them susceptible to “over-the-air” attacks like eavesdropping and spyware.

Goldsmith also provided a screenshot of a warning message he received while testing for interceptor activity:

Caution: The mobile network’s standard encryption has been turned off, possibly by a rogue base station (“IMSI Catcher”). Unencrypted calls not recommended.

Then Rep. Alan Grayson of Maryland drew attention to the issue in a July 2014 letter to FCC chair Tom Wheeler.

“I am disturbed by reports which suggest that the FCC has long known about the vulnerabilities in our cellular communications networks exploited by IMSI catchers and other surveillance technologies,” Grayson wrote.

Update December 28, 2020 4:23 p.m.: This article has been revamped and updated. You can review the original version, posted on September 5 2014, here.