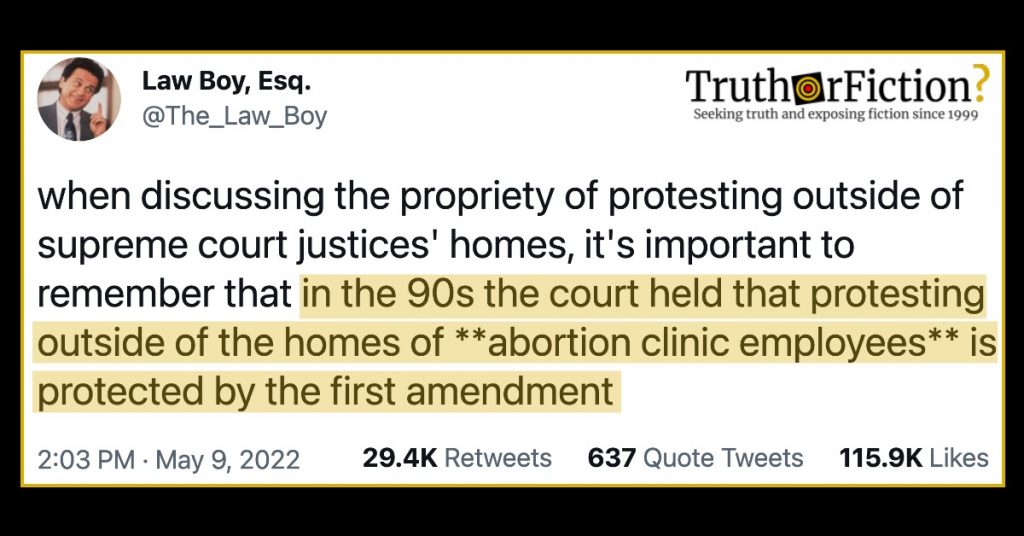

On May 9 2022, discourse about the SCOTUS/Roe v. Wade leak turned to ongoing protests outside the homes of Supreme Court justices — and a very popular tweet suggested that in the 1990s, that same court ruled that protests outside the homes of abortion clinic employees was protected speech under the First Amendment:

In the May 9 2022 leak, @The_Law_Boy asserted:

Fact Check

Claim: “when discussing the propriety of protesting outside of supreme court justices’ homes, it’s important to remember that in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the first amendment …”

Description: The claim is referring to the Supreme Court case Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc. in 1994, where part of the opinion held that Florida’s 300 foot ‘zone around residences’ of clinic staff involved a record which did not contain ‘sufficient justification for this broad a ban on picketing.’

when discussing the propriety of protesting outside of supreme court justices’ homes, it’s important to remember that in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the first amendment

A follow-up tweet didn’t provide additional details, instead adding:

there’s been chatter about 18 U.S. Code § 1507, which seems to make protesting outside of a judge’s home illegal. i’d think that if protesting outside of some random clinic employees’ house is protected, so is protesting outside of the homes of powerful public figures

As of May 10 2022, a leaked draft opinion by the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade had been international news for a solid week. But the tweet above involved a bit of context to fully understand and validate its claims.

What Was Going on With Protests Outside Justices’ Homes?

On May 9 2022, heated discussions took place across the country regarding the gathering of protesters outside Supreme Court justices homes:

The homes of Supreme Court justices are the newest site for protests over abortion access in the United States.

Activists gathered Saturday [May 7 2022] in the rain outside the Maryland residences of Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh to protest a leaked draft opinion reportedly supported by the court’s conservative majority … Protesters held signs that read, “Never Again” and “Don’t Tread on My Choice.”

Condemnations were predictably quick to follow. On the same date, the Washington Post‘s Editorial Board published a chiding editorial headlined, “Opinion Leave the justices alone at home”; its URL rendered as “washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/05/09/stop-protesting-outside-supreme-court-justice-houses.” It claimed that to “picket a judge’s home is especially problematic”:

The right to assemble and speak freely is essential to democracy. Erasing any distinction between the public square and private life is essential to totalitarianism. It is crucial, therefore, to protect robust demonstrations of political dissent while preventing them from turning into harassment or intimidation. An issue that illuminates this imperative in sharp relief is residential picketing — protests against the actions or decisions of public officials at their homes, such as the recent noisy abortion rights demonstrations at the Montgomery County dwellings of Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh. The disruptors wanted to voice opposition to a possible overruling of Roe v. Wade, as foreshadowed by a leaked majority draft opinion last week. What they mainly succeeded in doing was to illustrate that their goal — with which we broadly agree — does not justify their tactics.

The protests are part of a disturbing trend in which groups descend on the homes of people they disagree with and attempt to influence their public conduct by making their private lives — and, often, those of their families and neighbors — miserable. Those targeted in recent years include not just the conservative justices but also Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.); Mayor Ted Wheeler (D) of Portland, Ore.; and exiled Chinese dissident Teng Biao. To be sure, such tactics have a longer history: One of the ugliest manifestations was the antiabortion movement’s widespread deployment of pickets at the homes of abortion providers. What begins as peaceful protests can degenerate into violence: The oft-picketed author of Roe itself, Justice Harry A. Blackmun, was startled one evening in 1985 by the sound of a bullet shattering his Arlington apartment’s window.

Several news organizations covered the range of judgments on the propriety of protests outside justices’ residences, and a roundup by The Week (“Is it legal to protest outside a justice’s home?”) observed:

When Bill Kristol of The Bulwark took to Twitter urging demonstrators to refrain from protesting at private homes and places of worship, many users responded with derision. “Would you say a uterus is more, or less, private than a house?” asked journalist Heidi Moore.

Lindsey Boylan, one of the women who accused former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) of sexual misconduct, also responded to Kirstol [sic]. “Translation: Don’t be discourteous as people undermine your human rights. Don’t make the powerful uncomfortable in their community as they harm you intentionally,” she wrote.

Democratic strategist Max Burns wrote that conservatives “condemning the peaceful protesting outside Justice Kavanaugh’s home” were “absolutely silent when Christine Blasey Ford had to actually move because right-wing cranks were sending death threats right to her front door.” Ford wrote that she moved four times amid the controversy around Kavanaugh, and journalists gathered at her residence, but no protests were reported outside her home during Kavanaugh’s 2018 confirmation hearings.

U.S. Code § 1507

Both @The_Law_Boy and the Washington Post referenced U.S. Code § 1507, subtitled “Picketing or parading,” which broadly held:

Whoever, with the intent of interfering with, obstructing, or impeding the administration of justice, or with the intent of influencing any judge, juror, witness, or court officer, in the discharge of his duty, pickets or parades in or near a building housing a court of the United States, or in or near a building or residence occupied or used by such judge, juror, witness, or court officer, or with such intent uses any sound-truck or similar device or resorts to any other demonstration in or near any such building or residence, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.

Nothing in this section shall interfere with or prevent the exercise by any court of the United States of its power to punish for contempt.

A footnote indicated the statute dated back to 1950, and that it was last amended in 1994:

(Added Sept. 23, 1950, ch. 1024, title I, § 31(a), 64 Stat. 1018; amended Pub. L. 103–322, title XXXIII, § 330016(1)(K), Sept. 13, 1994, 108 Stat. 2147.)

‘It’s important to remember that in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the First Amendment’

@The_Law_Boy’s tweet certainly struck a chord with readers, amassing a six-figure “like” count in a single day.

Its vague reference to an opinion enshrining the right for anti-abortion protesters to demonstrate outside private homes was clearly compelling. However, it (and other tweets referencing it) rarely hinted as to what underlying decision it described:

A separate account mentioned a specific year, 1994:

At least one tweet mentioned a specific opinion, Madsen v. Women’s Health Center Inc.:

Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc.

In addition to the mention of that specific ruling, some people shared a screenshot of a website’s page about anti-abortion protest-related rulings in the 1990s:

That screenshot showed a piece (last updated in June 2011) on the First Amendment-centric site FreedomForumInstitute.org, entitled “Abortion Protests & Buffer Zones.” The assessment, which was attributed to “David L. Hudson Jr., First Amendment Scholar,” first referenced Madsen v. Women’s Health Center:

The issue of buffer zones for anti-abortion demonstrators has reached the Supreme Court several times in recent years beginning in 1994 with Madsen v. Women’s Health Center.

A Florida state court ordered that anti-abortion demonstrators could not protest within 36 feet of an abortion clinic, make loud noises within earshot of the clinic, display images observable from the clinic, approach patients within 300 feet of the clinic, or demonstrate within 300 feet of the residence of any clinic employee. The Florida Supreme Court upheld the injunction in its entirety.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the restrictions against demonstrating within 36 feet of the clinic (to the extent that the 36-foot buffer did not include private property), making loud noises within earshot of the clinic, and making loud noises within 300 feet of an employee’s residence. The Court rejected the prohibitions against displaying images, approaching patients within 300 feet of the clinic, and peacefully picketing within 300 feet of an employee’s residence. In reaching its decision, the Court announced a new test for cases in which speech is prohibited by an injunction: The injunction will be upheld unless it burdens more speech than is necessary to serve a significant government interest.

Subsequently, Hudson referenced a 2000 ruling, Hill v. Colorado, explaining:

In 1993, the Colorado Legislature enacted a law requiring protesters to stay eight feet from anyone entering or leaving an abortion clinic, as long as the clinic visitor is within 100 feet of the entrance. In 1995, three anti-abortion activists challenged the law, claiming it violated their free-speech rights. Both a trial court and state appeals court upheld the statute.

Hudson described a few years of litigation following that law about abortion protests. Hudson specifically described perspectives related to protests outside or in the vicinity of “public homes,” citing dissenting opinions from Justices Scalia and Kennedy:

The Court upheld the law by a 6-3 vote in its 2000 decision Hill v. Colorado. The majority reasoned that the law was not a speech regulation, but simply a “regulation of the places where some speech may occur.” The Court also emphasized that the law applied to all demonstrators regardless of viewpoint. The majority determined that the state’s interests in protecting access and privacy were unrelated to the suppression of certain types of speech. States and municipalities have special government interests in certain areas, including schools, courthouses, polling places, private homes and medical clinics, the Court said.

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a scathing dissent in which he accused the majority of manipulating constitutional doctrine in order to provide further protection for abortions: “What is before us, after all, is a speech regulation directed against the opponents of abortion, and it therefore enjoys the benefit of the ‘ad hoc nullification machine’ that the Court has set in motion to push aside whatever doctrines of constitutional law that stand in the way of that highly favored practice.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy also dissented, writing that the decision “contradicts more than a half century of well-established First Amendment principles.” Kennedy said the Colorado statute was a content-based law that restricted a specific type of speech, anti-abortion speech.

“Abortion Protests & Buffer Zones” contained links to copies of both Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc. and Hill v. Colorado. Justia summarized Madsen as follows:

After petitioners and other antiabortion protesters threatened to picket and demonstrate around a Florida abortion clinic, a state court permanently enjoined petitioners from blocking or interfering with public access to the clinic, and from physically abusing persons entering or leaving it. Later, when respondent clinic operators sought to broaden the injunction, the court found that access to the clinic was still being impeded, that petitioners’ activities were having deleterious physical effects on patients and discouraging some potential patients from entering the clinic, and that doctors and clinic workers were being subjected to protests at their homes. Accordingly, the court issued an amended injunction, which applies to petitioners and persons acting “in concert” with them, and which, inter alia, excludes demonstrators from a 36-foot buffer zone around the clinic entrances and driveway and the private property to the north and west of the clinic; restricts excessive noisemaking within the earshot of, and the use of “images observable” by, patients inside the clinic; prohibits protesters within a 300-foot zone around the clinic from approaching patients and potential patients who do not consent to talk; and creates a 300-foot buffer zone around the residences of clinic staff. In upholding the amended injunction against petitioners’ claim that it violated their First Amendment right to freedom of speech, the Florida Supreme Court recognized that the forum at issue is a traditional public forum; refused to apply the heightened scrutiny dictated by Perry Ed. Assn. v. Perry Local Educators’ Assn., 460 U. S. 37, 45, because the injunction’s restrictions are content neutral; and concluded that the restrictions were narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest and left open ample alternative channels of communication, see ibid.

@The_Law_Boy’s tweet asserted that “in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the first amendment.” Under “Held,” Madsen’s eighth point read:

The 300-foot buffer zone around staff residences sweeps more broadly than is necessary to protect the tranquility and privacy of the home. The record does not contain sufficient justification for so broad a ban on picketing; it appears that a limitation on the time, duration of picketing, and number of pickets outside a smaller zone could have accomplished the desired results. As to the use of sound amplification equipment within the zone, however, the government may demand that petitioners turn down the volume if the protests overwhelm the neighborhood.

Restrictions on protests outside the homes of clinic staff appeared later in the ruling, in a section reading:

The final substantive regulation challenged by petitioners relates to a prohibition against picketing, demonstrating, or using sound amplification equipment within 300 feet of the residences of clinic staff. The prohibition also covers impeding access to streets that provide the sole access to streets on which those residences are located. The same analysis applies to the use of sound amplification equipment here as that discussed above: the government may simply demand that petitioners turn down the volume if the protests overwhelm the neighborhood.

As for the picketing, our prior decision upholding a law banning targeted residential picketing remarked on [ MADSEN v. WOMEN’S HEALTH CTR., INC., ___ U.S. ___ (1994) , 20] the unique nature of the home, as “‘the last citadel of the tired, the weary, and the sick.'” We stated that “‘[t]he State’s interest in protecting the wellbeing, tranquility, and privacy of the home is certainly of the highest order in a free and civilized society.'”.

But the 300-foot zone around the residences in this case is much larger than the zone provided for in the ordinance which we approved in Frisby. The ordinance at issue there made it “unlawful for any person to engage in picketing before or about the residence or dwelling of any individual.” The prohibition was limited to “focused picketing taking place solely in front of a particular residence.” By contrast, the 300-foot zone would ban “[g]eneral marching through residential neighborhoods, or even walking a route in front of an entire block of houses.” The record before us does not contain sufficient justification for this broad a ban on picketing; it appears that a limitation on the time, duration of picketing, and number of pickets outside a smaller zone could have accomplished the desired result.

Hill v. Colorado largely restricted the activities of protesters outside clinics, and mentioned homes only in passing or relation to cited prior rulings. However, Madsen did uphold and enshrine the right to protest outside homes, in the context of both anti-abortion protesters and clinic employees.

Summary

Discourse regarding May 2022 protests outside justices homes included a popular tweet by @The_Law_Boy asserting that “in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the first amendment.” Although the tweet made no mention of when in the 1990s the ruling in question was handed down nor did it reference the ruling, it presumably described 1994’s Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc.

Part of the opinion held that Florida’s 300 foot “zone around the residences” involved a record which did not contain “sufficient justification for this broad a ban on picketing.” In that ruling the Court upheld the lower court’s decision to restrict specific activity outside the clinics themselves, but found the lower court’s 300 foot “buffer zone” around homes was too “broad.”

- 'when discussing the propriety of protesting outside of supreme court justices' homes, it's important to remember that in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the first amendment' | @The_Law_Boy/Twitter

- 'when discussing the propriety of protesting outside of supreme court justices' homes, it's important to remember that in the 90s the court held that protesting outside of the homes of **abortion clinic employees** is protected by the first amendment' | @The_Law_Boy/Twitter

- White House responds to abortion-related protests at homes of Supreme Court justices

- Opinion: Leave the justices alone at home

- U.S. Code § 1507 - Picketing or parading

- Is it legal to protest outside a justice's home?

- 'The Supreme Court ruled years ago that protesting outside abortion clinic employees' homes is protected speech under the 1A' | Twitter

- 'Oh no did they have their privacy violated?! The Supreme Court ruled in 1994 that protesting outside of the homes of abortion clinic employees is protected by the first amendment...Enjoy your beers guys...Hope you get zero sleep. #RoeVWadeprotest #RoeVsWade #FreshVoicesRise' | Twitter

- 'The Supreme Court literally found that anti-abortion protestors had a constitutional right to protest outside random abortion clinic employees homes in Madsen v. Women's Health Center, Inc.' | Twitter

- 'Not just abortion clinics but homes of abortion clinic employees! If the Supreme Court can decide it's OK for anti-choice protestors to protest outside of the home of private citizens, it surely must be OK to protest at the homes of govt officials!' | Twitter

- Abortion Protests & Buffer Zones

- MADSEN v. WOMEN'S HEALTH CTR., INC. | Findlaw

- Madsen v. Women's Health Center, Inc. | Wikipedia

- HILL v. COLORADO