Netflix released Black Mirror standalone special “Bandersnatch,” which featured an interactive “choose your own adventure” style plot, on December 28, 2018. Immediately, viewers began dissecting its elements — chief among them claims that the story was (at least in part) based on real-life events.

“Bandersnatch” follows a young British video game designer named Stefan who begins to develop a role-playing video game of the same title for a fictional company (called Tuckersoft) in 1984, seeming to lose his grip on reality as the show progresses.

One of the claims circulating immediately after the episode was released is that the game featured in the film was, in fact, a real title from the 1980s.

This rumor was in keeping with years of interest in video game urban legends and creepypastas, stories which ranged from super-hidden secret levels to content that self-destructed or drove its creators or players insane. Aspects of the episode and the game itself evoked urban legends about the almost-certainly fictitious game Polybius, the mythos surrounding it, and its purported inducement of psychosis in players:

According to the legend, Polybius was a game that appeared in a few arcades in Portland, Ore., for a short time in 1981. The cabinet was supposedly completely black (minus the logo), and the game was supposed to be very similar to Atari’s shoot ’em up Tempest, except for the addition of Pac-Man-type mazes and logic puzzles, and the fact that it drove people insane. Kids hooked on the game began experiencing side effects like nausea, sleep disturbance and aversion to video games.

The lore of Polybius is probably the most well-known and mysterious of its sort, dating back as far as the late 1990s on early message boards:

That’s the story, at least. This legend is one of the big unsolved mysteries of the gaming world, though most concede that the game never existed. It’s since become an urban legend on gaming and conspiracy websites and the internet horror wiki Creepypasta, and like all good stories, it is kept alive by its fans.

The 1998 post was shared with others in 2000 on a precursor to internet forums called Usenet, and seemingly sparked further lore about the game; by 2003 it appeared in a list of urban legends in GamePro magazine. In coinop.org’s comment section in 2006, someone by the name of Steven Roach added to the story: it was created by a company he and a few other naive programmers began, called Sinneslöschen, he explained. They were hired by a separate “South American company” to do the work, he claimed; they were merely in over their heads with their advanced, accidentally dangerous graphics … In response, coinop.org amended its entry in 2009 with a rebuttal, saying “Steven Roach is full of himself, and knows nothing about this game.” The response claimed staff was planning to sort it all out by flying to the Ukraine; “Stay tuned.”

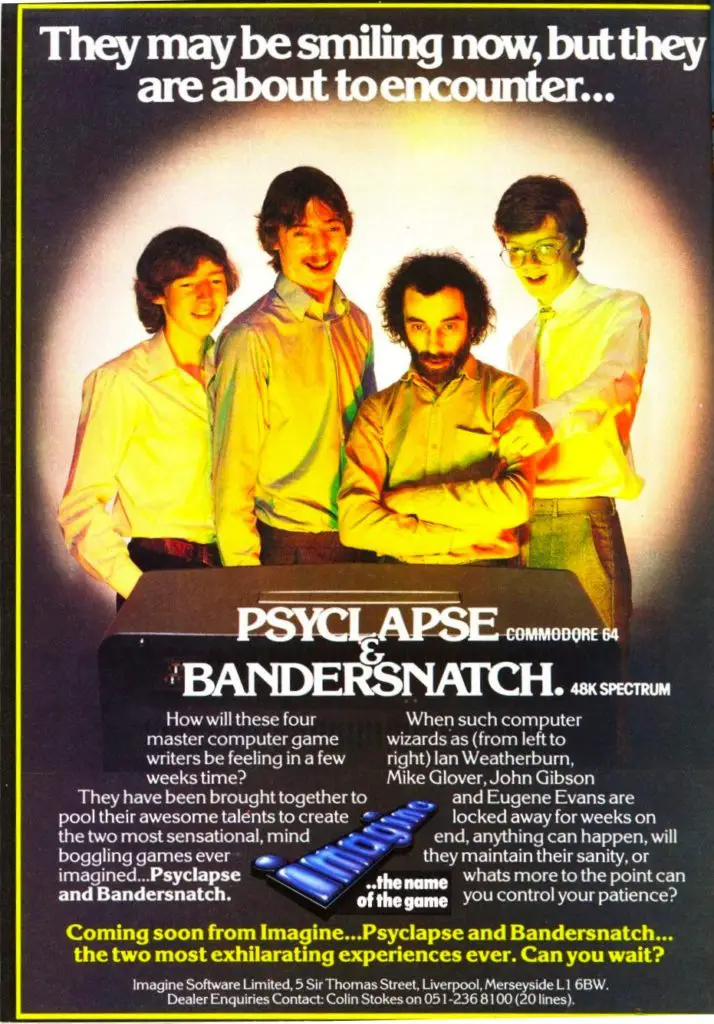

Adding to the intrigue, a Reddit user on r/games started a thread on December 29, 2018, titled “Poster for ‘Bandersnatch’ the game, a project which never saw the light of day — the game was developed in 1984, the same year the Black Mirror episode takes place.” That post linked to a brief BBC documentary about the downfall of British video game developer Imagine Software, and added a promotional poster for two Imagine Software titles — Psyclapse and Bandersnatch:

Versions of the Psyclapse and Bandersnatch promotional poster were shared in various places online as early as 2009, ruling out a convincing fake crafted by fans or something shared as part of a marketing campaign.

An exhaustive item about the companies and developers involved in the development of Bandersnatch and related titles described it as “the first of the megagames,” detailing a history that bore many parallels to the development narrative in the 2018 Netflix film Bandersnatch:

So, [developers Ian] Hetherington and [Dave] Lawson were seemingly back in business [with a company called Fireiron], picking up where Imagine had left off. This included, unfortunately, the same tendency toward wildly overambitious pronouncements. “Originally at Imagine we were working on seven megagame titles,” said Lawson. “I see no reason why we shouldn’t continue with them all.” In reality, only two megagames had progressed far enough to have titles, and only one, Bandersnatch, had had significant programming done. Given these realities, it was perhaps dangerous to trust too much in Lawson’s assertion that the old Speccy version of Bandersnatch was “90 per cent complete, ” and could be ported to the QL and completed there in very short order. Still, the new arrangement didn’t seem a bad one, all told. There was even something in it for Imagine’s long-suffering creditors, should the megagames prove successful.

….The many creditors who had had faith in Imagine, only to be bilked out of many thousands of pounds — not to mention the many dozens of employees who had lost their jobs — weren’t quite so willing to declare the events of just six months previous to be ancient history. “The lying and deception” Hetherington and Lawson had engaged in, Bruce Everiss said, “were almost boundless.” Assuming he was correct, it certainly did seem like those actions ought to have consequences. Still, there was only so much outrage to be generated; the scandal of Imagine did gradually fade into the past, giving at last to Hetherington and Lawson the fresh start they looked for.

However, the piece quoted here didn’t really get into specifics about the apparently ill-fated release of Bandersnatch and the early gaming title intrigue surrounding it in 1984. The events in Netflix’s “Bandersnatch” episode of Black Mirror began on July 9, 1984 — the same day the real-life company Imagine went dark. Contemporaneous news articles copied to the internet by gaming historians and subsequently archived reported the company’s dissolution and fate of its projects:

IMAGINE. the flamboyant Liverpool software company. whose financial problems have been deepening since February [1984], is now insolvent.

Magazine publishers VNU petitioned for a winding up order to be brought against the company on Monday. July 2 [1984].

The crisis means that the future of Imagine’s two Mega-games is now uncertain.

The situation has been exacerbated by a bitter internal split between general manager Bruce Everiss and his co-directors.lan Hetherington and Dave Lawson. The position of Imagine’s other director, Mark Butler is still not clear. Bruce Everiss resigned as director and general manager at midday on Friday, June 29 [1984].

Central to the disagreement is a new company called Finchspeed set up by Hetherington and Lawson to raise funds. Hetherington, Lawson and Mark Butler each have a one-third share in the new company.

That 1984 article did not mention Bandersnatch or Psycalpse by name, but it described the extensive marketing committed to the releases at the time the company folded:

Imagine’s two Megagames were originally planned to be launched with an extensive and distinctive promotional campaign. Marble slabs were to be laid in Hyde Park with the names of the games etched into them and the BBC were filming a documentary on their making.

Ultimately, the game Bandersnatch never saw the light of day under its planned title. However, its components were purportedly utilized in the development of the 1986 game Brataccas:

Brataccas had its origins in Bandersnatch, one of a pair of ambitious “Megagames” planned by Imagine Software. Along with Psyclapse, another proposed Megagame, Bandersnatch was eagerly anticipated by teaser adverts placed in the computer press … throughout 1984.

Bandersnatch was originally intended for release on the 8-bit ZX Spectrum home computer, and would have set a new price point for computer games (£39.95 vs. the standard rates of the time of between £5.95 and £11.95). It was intended that the game would have required a cartridge or dongle to support the demands of the game.

However, before any of the Megagames had been completed, Imagine Software went bankrupt owing to financial mismanagement, with the spectacular demise being shown in a BBC documentary named Commercial Breaks.

A new company called Finchspeed (formed from the remnants of Imagine) acquired the Bandersnatch rights and sold an option on the game to Sinclair Research Ltd. Finchspeed itself folded, but a complete working version was developed for the Sinclair QL. The directors Dave Lawson and Ian Heatherington then formed Psygnosis and the now-complete game (renamed Brataccas) was released on the Atari ST, Amiga and Macintosh.

Bandersnatch (the game) has been described as “vaporware” in the history of gaming, although it was widely believed to be the basis of Brataccas‘ release in 1986 and was well-documented as an in-progress project when Imagine closed its doors in July 1984. When Brataccas was finally released, it, like the game in certain plotlines in the Black Mirror episode, received mixed reviews.

- 16 Of The Spookiest Video Game Urban Legends

- 8 Creepy Video Game Urban Legends (That Happen to Be True)

- 15 Video Game Urban Legends That Will Freak You Out!

- Poster for "Bandersnatch" the game, a project which never saw the light of day — the game was developed in 1984, the same year the Black Mirror episode takes place

- The Urban Legend of the Government’s Mind-Controlling Arcade Game

- Games on the Mersey, Part 4: The All-Importance of Graphics

- Popular Computing Weekly 5-11 July 1984

- Brataccas

- Imagine Software

- From Then to Now - Imagine Software