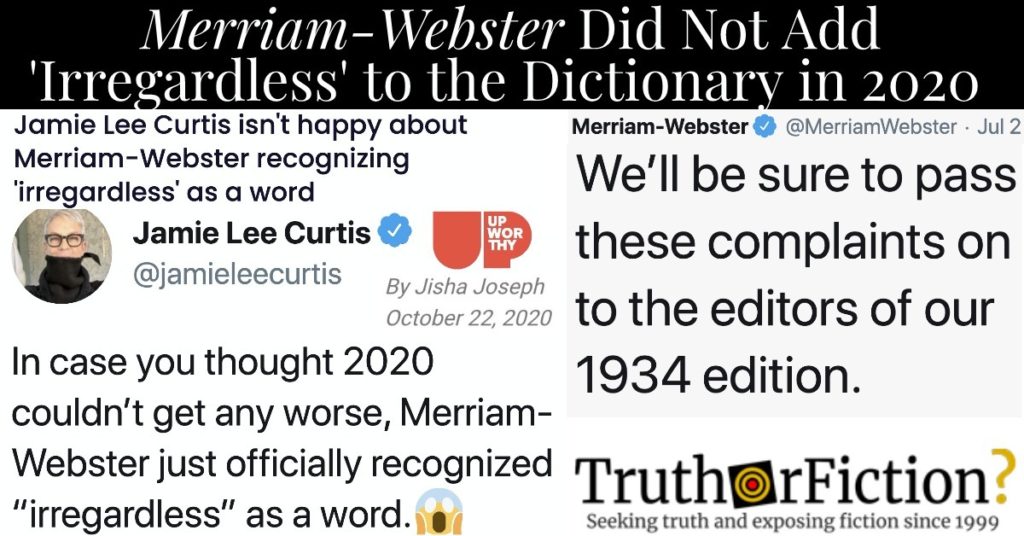

On October 22 2020, Upworthy published a post (“Jamie Lee Curtis isn’t happy about Merriam-Webster recognizing ‘irregardless’ as a word”) which — as might be expected — was shared by numerous social media accounts alongside their own opinions:

On October 23 2020, Google Trends demonstrated that Upworthy’s blog post caused interest in a constellation of related searches to spike in popularity. Users searched for “irregardless,” “Jamie Lee Curtis,” “merriam webster irregardless,” “when was irregardless added to the dictionary,” and “irregardless added to dictionary” repeatedly on or after October 22 2020:

But the tweet was not immediately visible on Curtis’ timeline on October 23 2020. In fact, we had to go back several months, to July 6 2020, when Curtis tweeted the “irregardless” commentary seen in the Upworthy screenshot:

It is true that the official Twitter account for Merriam-Webster addressed the word “irregardless” on July 1 2020. The dictionary retweeted a since deleted tweet, kicking off a predictable firestorm of prescriptivist pedantry:

That deleted tweet (archived here) was also originally published on July 1 2020. In it, @iowahawkblog shared a screenshot of the dictionary entry for “irregardless,” musing, “It was a good run, English language”:

On July 1 2020, Merriam-Webster‘s reply in part was a link to “Usage Notes,” which bore no visible date. However, source code showed the page was published on July 27 2018, not 2020.

That entry (“Is ‘Irregardless’ a Real Word?” and subtitled “LOL, the look on your face right now”) began:

It has come to our attention lately that there is a small and polite group of people who are not overly fond of the word irregardless. This group, who we might refer to as the disirregardlessers, makes their displeasure with this word known by calmly and rationally explaining their position … oh, who are we kidding … the disirregardlessers make themselves known by writing angry letters to us for defining it, and by taking to social media to let us know that “IRREGARDLESS IS NOT A REAL WORD” and “you sound stupid when you say that.”

We define irregardless, even though this act hurts the feelings of many. Why would a dictionary do such a thing? Do we enjoy causing pain? Have we abdicated our role as arbiter of all that is good and pure in the English language? These are all excellent questions (well, these are all questions), and you might ask them of some of these other fine dictionaries, all of whom also appear to enjoy causing pain through the defining of tawdry words.

Pointing to other dictionaries with “irregardless” entries, Merriam-Webster continued:

The reason we, and these dictionaries above, define irregardless is very simple: it meets our criteria for inclusion. This word has been used by a large number of people (millions) for a long time (over two hundred years) with a specific and identifiable meaning (“regardless”). The fact that it is unnecessary, as there is already a word in English with the same meaning (regardless) is not terribly important; it is not a dictionary’s job to assess whether a word is necessary before defining it. The fact that the word is generally viewed as nonstandard, or as illustrative of poor education, is likewise not important; dictionaries define the breadth of the language, and not simply the elegant parts at the top.

[…]

If we were to remove irregardless from our dictionary it would not cause the word to magically disappear from the language; we do not have that kind of power. Our inclusion of the word is not an indication of the English language falling to pieces, the educational system failing, the work of the cursed Millennials, or anything else aside from the fact that a lot of people use this word to mean “regardless,” and so we define it that way.

In a July 3 2020 “Words of the Week” post, Merriam-Webster once again attempted to explain that “irregardless” was not a recent addition. Preceding a massive list of existing usage of the word “irregardless” was the following context:

‘Irregardless’

From time to time it is drawn to our attention that certain parties find it objectionable that we have included irregardless in our dictionary. The outrage presumably springs from our allowing this callow arriviste to rub elbows with other, nobler, words; the very presence of irregardless besmirches such entries as asshead, ninnyhammer, and schnook.Irregardless is included in our dictionary because it has been in widespread and near-constant use since 1795. We must warn you, gentle readers, that there are some other words which appear for the first time this very same year that we define in our dictionary. Yes! We have allowed entry to such Johnnies-come-lately as bewhiskered, citizenry, and terrorism, all of which have their earliest written evidence the same year as irregardless.

We do not make the English language, we merely record it. If people use a word with consistent meaning, over a broad geographic range, and for an extended period of time chances are very high that it will go into our dictionary. As a way of showing why we included irregardless we have decided to show but a small portion of the citations that we have of this word’s use.

On July 2 2020, @MerriamWebster addressed the flood of hand-wringing tweets about “irregardless,” quipping that they would ensure that all complaints were forwarded to editors of their 1934 edition:

Upworthy opted to feature Curtis’ anti “irregardless” tweet as the singular focus of an article on October 22 2020, reviving an already inaccurate controversy over Merriam-Webster‘s purported addition of “irregardless” in 2020. That controversy appeared to have kicked off when Twitter user @iowahawkblog tweeted a lament for the English language alongside a screenshot of the word’s dictionary entry in July 2020. Merriam-Webster attempted to explain that the word was not invented nor newly included in 2020, but their pleas fell on deaf ears. A day later, the dictionary’s Twitter feed surrendered, promising to “pass these complaints on to the editors of our 1934 edition.”

- Jamie Lee Curtis isn't happy about Merriam-Webster recognizing 'irregardless' as a word

- Jamie Lee Curtis isn't happy about Merriam-Webster recognizing 'irregardless' as a word

- Irregardless, Jamie Lee Curtis | Google Trends

- Jamie Lee Curtis | Twitter

- Yep. English is literally dead.

- It was a good run, English language

- Is 'Irregardless' a Real Word?

- The Words of the Week - 7/3/20

- We’ll be sure to pass these complaints on to the editors of our 1934 edition.

- Regardless Of What You Think, 'Irregardless' Is A Word