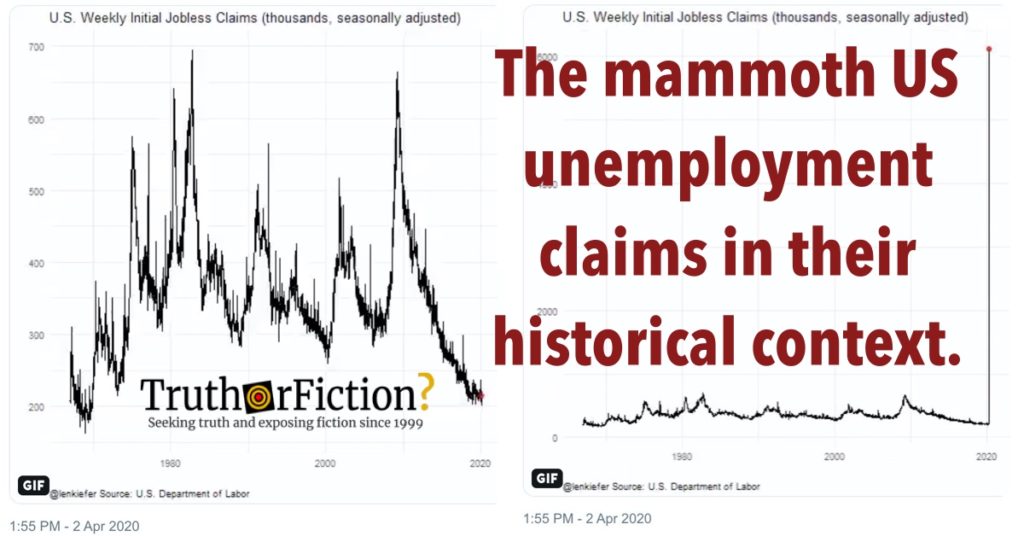

In early April 2020, the animated image below spread on Facebook and Twitter, bearing the label “U.S. Weekly Initial Jobless Claims (thousands, seasonally adjusted)”; no source for the shocking graph was immediately available.

Blurry text at the bottom appeared to hint at a source, but it was difficult to read without context:

(Although the image spread via the source linked above, we copied it to Imgur for ease of embedding.)

The image began with a rising and falling line graph, showing first some spaced out peaks and valleys. The line continued condensing, the peaks becoming more concentrated, until what first looked almost like an EKG with even spikes and drops became nearly a flat line dwarfed by the graph’s final straight-line uptick.

As the graph’s x axis approached 2020 it began with a valley — rapidly transitioning to a sharp vertical ascent parallel to the y axis. At the the end of the GIF, the parallel line continued skyrocketing up, straight through several of the y axis’s metric of thousands.

Bear in mind that the graph’s vertical x axis represented one of two values — first, singular years (1967, then 1968), extending to the year 2020. Its y axis was numbered starting at 100 and ascending to more than 6,000, increasing by orders of magnitude at the very end. Huge spikes in the late 1960s were visualized just under 300 (thousands), rising to between 500 and 600 (thousands) in the 1970s. In the early-to-mid 1980s, the graph featured new highs of just under 700,000.

That near-700,000 peak was not reached again until the very late 2000s (around 2008 or 2009), where the graph showed numbers nearly as high as the previous record high two and a half decades earlier. And from that part onward, the graph steadily decreased in a sustained downtrend, dropping below 300,000 around 2015, and again to just above 200,000 as the graph approached the year 2020.

Then, the final moments of the animation put the x axis (beginning in the late 1960s) into staggering, alarming context. While its metric appeared to have previously had giant spikes matched with huge dips, representing times of record low unemployment and times of trending jobless claims, through seven decades, that line in perspective was nearly flat when it was dwarfed by the 2020 spike.

For additional context, those numbers did not seem to be adjusted for increases in the population [PDF]. In 1970 (near the very start of the graph’s x axis), there were around 203,200,000 Americans according to the United States Census. In 2010, there were 308,700,000 Americans — a number that rose to about 330,559,000 in 2020:

(Numbers in purple were projections by the Census as of 2014, and did not match current estimated population numbers for the United States.) Between the graph’s beginning years (around 1970) and its 2020 end, the United States population rose about 62.7 percent. Had the graph’s increases remained under 1,000 and 2,000 thousands or between one and two million, the increase in total Americans would be a bit more relevant to that spike. However, the peaks and valleys stayed relative to one another from the late 1960s through 2020 — until the big straight line.

Iterations

We first spotted the graph being shared by individuals on Facebook, mainly via this link. We subsequently located the same animation in an April 2 2020 tweet from Ben Riley-Smith:

The mammoth US unemployment claims in their historical context. pic.twitter.com/UNDwhBMpZt

— Ben Riley-Smith (@benrileysmith) April 2, 2020

Riley-Smith described it as “mammoth U.S. unemployment claims in their historical context,” adding a source and specific numbers in two follow-up tweets:

His name is on there but for those asking all the credit for this wizzardry goes to creator @lenkiefer.

And the stats: that final figure is 6.6 million. Previous high before coronavirus was not quite 700,000.

@lenkiefer is Len Kiefer, Deputy Chief Economist for lender Freddie Mac.

Graph source and attendant data

On April 2 2020, Kiefer tweeted two versions of the graph animations (with much lower engagement than Riley-Smith’s tweet):

One of the graphs is the one in the embeds, and the other was “U.S. weekly initial jobless claims as a percent of the labor force.” Once again, the record highs were dwarfed by the new numbers; although the chart highs maxed out between 0.4 and 0.6 percent of the labor force, the illustrated peak was measured at four percent of the labor force in total.

On April 3 2020, Kiefer stated that some suspected that the seasonal adjustment might be distorting the data, presumably referencing the eye-catching line-spike at the end. But he shared the “unadjusted claims data,” which bore a similar peak at just under 6,000,000 (versus the one near 6,500,000):

On April 3 2020, Kiefer shared an attendant blog post published to LenKiefer.com, which explained his source and the context of the figures in the graphs:

[On April 3 2020,] the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly employment situation summary for March 2020. While many were expecting the U.S. labor market to show some weakness as the U.S. economy shuts down to battle COVID-19, the magnitude of the contraction surprised many. Because the reference week for the employment report was March 8th through March 14th, before the nationwide shutdown took full effect, many were expecting a relatively mild report.

Instead, we got a shock. Nonfarm payrolls, which had increased for 113 consecutive months, contracted by 701,000. And the unemployment rate increased from 3.5% in February to 4.4% in March.

With weekly initial jobless claims increasing rapidly, with over 10 million claims (on a seasonally adjusted basis) filed after the March [2020] reference week the April [2020] report will likely show significant job losses above what we saw in March [2020].

It’s likely going to be a few tough months ahead.

Below, I share some charts on the labor market, and the R code I used to generate them.

Kiefer explained that the data was sourced from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ March 2020 recap report, released in early April 2020. Although one of Kiefer’s graphs was widely shared and viewed, it lacked his commentary from his written analysis. Namely, a projection that April 2020 “will likely show significant job losses above what we saw in March [2020.]”

Kiefer embedded graphs and animations, concluding:

Many smart analysts knew that [the] last two weeks of claims [in March 2020] covered weeks after the reference week, so [April 3 2020]’s employment situation was likely to understate the magnitude of job losses. Consensus forecasts were for employment to contract 100,000 in March [2020]. That would still be very bad, and break string of 113 consecutive months of job gains. Instead employment fell by 701,000. That is the sharpest decline since March of 2009, when we lost 800,000 jobs.

After the Great Recession I used to think we would use fractional multipliers to describe future events. Something like 0.1x, 0.2x, where X was the indicator in the Great Recession. Right now it looks like we might need to use whole number multipliers, 1x, 2x, etc. Hopefully we’ll be able to apply those same multipliers once we start to recover.

Stay safe out there.

Kiefer also linked to the official Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report, which formed the basis of the graphs and was indeed released on April 3 2020. That report stated in part:

Total nonfarm payroll employment fell by 701,000 in March [2020], and the unemployment rate rose to 4.4 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported [on April 3 2020]. The changes in these measures reflect the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) and efforts to contain it. Employment in leisure and hospitality fell by 459,000, mainly in food services and drinking places. Notable declines also occurred in health care and social assistance, professional and business services, retail trade, and construction.

[…]

In March [2020], the unemployment rate increased by 0.9 percentage point to 4.4 percent. This is the largest over-the-month increase in the rate since January 1975, when the increase was also 0.9 percentage point. The number of unemployed persons rose by 1.4 million to 7.1 million in March [2020]. The sharp increases in these measures reflect the effects of the coronavirus and efforts to contain it.

Kiefer and the BLS report referenced compounding month-over-month increases, and the BLS report repeatedly described “the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) and efforts to contain it” as a major factor.

Confounding factors

Dean Baker, Senior Economist at the Center for for Economic and Policy Research, was tagged by one Twitter user who saw the animations and asked for comment. Baker explained that the rates were at least in part due to unique aspects of an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic:

As Baker indicated, the spike was in part due to the number of workforce participants under orders not to work due to the pandemic. He added that in his opinion, the government ought to “keep people whole for the next two months” due to ongoing stay-at-home orders in many states. In other words, the numbers were unprecedented — because the situation was unprecedented in modern times. The pandemic’s far-reaching effects shifted statistics and figures in multiple directions simultaneously.

Baker also said “we shouldn’t be too upset” about the figures, and mentioned a “rescue bill” to offset loss of wages for affected Americans. Another commenter reiterated Baker’s response in plainer terms:

The New York Times blog The Upshot published a report on the same figures on April 3 2020, updating it on April 6 2020. That piece began with some background about why unemployment numbers were both incredibly volatile and on the surface shocking:

The jobless rate [on or around April 3 2020] is almost certainly higher than at any point since the Great Depression. We think it’s around 13 percent and rising at a speed unmatched in American history.

The labor market is changing so fast that our official statistics — intended to measure changes over months and years rather than days or weeks — can’t really keep up. But a few simple calculations can help piece together a reasonable approximation.

Be warned, these numbers yield an imprecise estimate of today’s unemployment rate, and the truth could easily be quite a lot higher or lower. This is not an estimate of the official unemployment rate for March [2020], which reports the state of the economy a few weeks [prior] when the labor market was in better shape, nor is it a forecast for the official rate in April [2020].

The Upshot further explained the definitions behind the figures:

There are important differences between who receives unemployment benefits and whom the official statistics measure as unemployed. (The former is based on eligibility for unemployment insurance, while the latter is based on who responds to government surveys that they are actively looking for work.) But it is likely that nearly all of these people will show up in the official statistics. After all, you qualify for unemployment benefits only if you’re actively looking for work.

The analysis also described several confounding factors, issues large enough to have a strong impact, such as:

- A growing “gig economy” whose participants may not be initially counted, and who might qualify for benefits under circumstantially expanded programs;

- Effects of a surge in claims on states’ unemployment offices and bureaus, delaying the reporting of figures;

- A contrast between a fast-moving situation (illustrated by the animation’s spike) and a cut date for the data. Although the report was released on April 3 2020, it measured through March 28 2020, and we’re here discussing in on April 7 2020;

- The impact of a sharp drop in hiring, a metric which goes hand in hand with job loss and offsets those figures under normal circumstances.

The outlying high numbers were tied to a broader aberrant situation — the COVID-19 pandemic, its progression, and factors such as temporary job loss for workers who might be able return to their jobs. On top of that, the pandemic’s duration was unknown and volatile. If COVID-19 cases continued rising, so too would atypical employment figures; conversely, a slow-down in new infections would eventually be followed by the labor force slowly resuming its duties.

The far-reaching effects of variables could not reasonably be measured well, as the blog explained:

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that in a typical month, nearly six million workers are hired, a rate of 1.5 million per week. Again, it’s hard to know how much that has fallen, but if the hiring rate fell by a fifth over the past three weeks, that would mean that roughly one million fewer people found work than might otherwise be expected to.

At this point, our calculations show 16 million more people without work, for an unemployment rate of 13 percent … Given the many uncertainties involved, perhaps it’s better to say that unemployment has risen by 10 million to 20 million, which means that the unemployment rate is probably between 10 percent and 15 percent. That might sound like an unsatisfyingly unclear conclusion, but it’s a product of how poorly our official statistics track labor market changes from day to day, and how rapidly the economy is shutting down.

Conclusion

An animated graph titled “U.S. Weekly Initial Jobless Claims (thousands, seasonally adjusted)” went massively viral on social media platforms, decoupled from its source data due to limitations on labeling. Those numbers were real and originated with an April 3 2020 BLS report, but they were not entirely reflective of reality in terms of genuine unemployment. Blanket stay-at-home orders and expansion of unemployment benefits to those temporarily furloughed or out-of-work were counted in, and an unknown number of people had yet to be counted. It was further impossible to measure how many jobs would resume versus companies or businesses never to reopen, whether the scenario was stimulating or depressing the “gig economy,” and what the long term labor-related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic might be. Although the graph had underlying real numbers, they were hobbled by myriad variables in an unprecedented global pandemic.