April 2019 saw the culmination of a months-long popular uprising in the country of Sudan, when its former president Omar al-Bashir stepped down from his post. The Sudanese military quickly took control of the country in what it called a transitional phase.

In the weeks following al-Bashir’s ouster, however, clashes became both deadlier and more sustained as the military refused to transfer power to a legislative body, including a massacre of peaceful protesters attending a sit-in on June 3 in Khartoum:

A TMC spokesman earlier said an investigation had been launched into the attack on the protest camp earlier this week and that several military officers had been arrested over the “violations”.

Gen Shams Eddin Kabashi did not elaborate at a news conference late on Thursday beyond saying the alleged offences were “painful and outrageous”. He rejected all calls for an international investigation.

“We feel sorry for what happened,” said Kabashi. “We will show no leniency and we will hold accountable anyone, regardless of their rank, if proven to have committed violations.”

The exact death toll in the attack on the protest camp on 3 June is unclear because many bodies were dumped in the Nile in an attempt to hide the scale of the killing. Hundreds more were injured in widespread beatings and assaults. Doctors also told the Guardian paramilitaries may have carried out more than 70 rapes during the crackdown.

Stalled talks between the council and an alliance of opposition groups over who should control a transition towards elections collapsed after security forces attacked the sit-in protest .

As protesters continue to demand civilian rule, the country has shut down its internet access, forcing people to communicate via SMS messages. This has created an information void that — as always happens when information voids exist — is being filled by opportunistic disinformation purveyors who appear to be looking for ways to increase their engagement on social media.

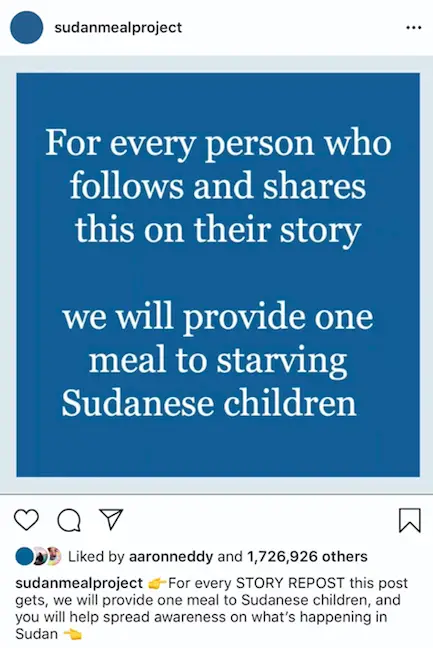

Instagram, a platform that relies on photographs and visual memes that do not often offer either citations or deep analysis, has been increasingly used to spread misinformation and disinformation. This has not gone unnoticed by those willing to exploit geopolitical uncertainty for their own ends. “Sudan has been ravaged by violence since its former president, Omar al-Bashir, was ousted in a military coup in April,” wrote reporter Taylor Lorenz in The Atlantic:

On June 3, the conflict boiled over when scores of protesters were killed, including 26-year-old Mohamed Hashim Mattar. His Instagram avatar at the time of his death was steel blue, and after he was killed, the color became a symbol of the pro-democratic uprising. Hundreds of thousands of users have made their profile photos blue in a sign of solidarity.

In addition to misrepresenting their intentions, these accounts are sowing misinformation. A since-deleted post on @SudanMealsProject, copied and shared elsewhere, stated that “more than six million people need urgent food assistance”—but that figure refers to South Sudan, not Sudan. It also stated, “Near-famine conditions are predicted in four of Sudan’s states.” This also is true of only South Sudan, which has been a separate independent nation since 2011. “It’s difficult to argue that [these campaigns] are effectively raising awareness when they’re using facts and figures relating to an entirely different country,” said English.

Image courtesy: The Atlantic

When The Atlantic contacted @SudanMealProject about its claims that it would provide one free meal to Sudanese children for every person who “followed” and “shared” their posts, the administrator was unable to provide the names of any aid groups with whom it was working or examples of its ability to provide meals for Sudanese children — which would be no small task given the upheaval in which the country is embroiled.

“What I am obtaining is followers and exposure,” the administrator for @SudanMealProject told me. “… I love how the left likes to twist these stories.”

The administrator later deleted the account’s post, updated its bio, and changed its handle to @SudanPlan. After The Atlantic contacted Instagram, the company removed the account for violating its policies. Many copycat accounts are still live. “We will continue to look into this matter and disable further accounts we find in violation of our policies,” an Instagram spokesperson said.

Engagement-bait, like clickbait and like-bait, is a thriving industry on social media. Like other platforms, Instagram and its parent company Facebook have prioritized “engagement,” creating opportunities for scammers and hoaxers to thrive. Often, engagement-bait plays on seemingly wholesome stories and emotional ploys to push online interactions, such as the “grandma’s 100th birthday” story we debunked in January 2019 that showed a photograph of an elderly women with the following plea:

Today’s is my Grandma’s 100th Birthday. She requested me to post her pic on Internet to get some good wishes. [heart emoji, angel emoji]

Like-farming and response-farming (also called clickbait) are two common ways that legitimate companies regularly use to create a buzz an increase their visibility and profile online, as social media’s algorithms reward engagement with higher visibility. However, some less scrupulous types will gather clicks, likes, and responses to indicate popularity and engagement, then scrub the original content and replace it with something else to bypass constraints. This can lead to unpleasant side effects, such as malware and disinformation infestations. As we wrote about “grandma” in January 2019:

Posts like the “grandma” one fell into the category of engagement bait, a practice Facebook maintained that it would downrank in December 2017:

People have told us that they dislike spammy posts on Facebook that goad them into interacting with likes, shares, comments, and other actions. For example, “LIKE this if you’re an Aries!” This tactic, known as “engagement bait,” seeks to take advantage of our News Feed algorithm by boosting engagement in order to get greater reach. So, starting [in December 2017], we will begin demoting individual posts from people and Pages that use engagement bait.

Not long after Facebook announced its purported crackdown on “engagement bait,” The Next Web described the move as “long overdue.” In that piece, TNW provided an example of how unscrupulous pages with bad motives were able to “game” Facebook’s algorithms via the tactic:

Engagement bait is an incredibly effective growth-hacking technique. Perhaps the best-known example of a page using it to great success is Britain First — a once-obscure far-right British political party who quickly came to boast the most followed Facebook page in UK politics, largely thanks to its use of Facebook.

It quickly reached over a million followers thanks to its post, which typically contained populist rhetoric in all-caps, and usually contained some permutation of the words “SHARE IF YOU AGREE.”

This can also infect the national and international discourse by showing what appears to be enthusiasm for an unpopular idea, artificially inflating certain people or ideas by creating what appears to be grassroots engagement using the same bait-and-switch techniques. In cases like these, it is best to consider that engagement (like its close cousin, ratings) is best used as measurement of an existing post’s popularity rather than an aspirational goal in and of itself, and to view all “like and share” or “follow and share” exhortations, no matter who appears to be behind them, with extreme skepticism.

- Sudan and the Instagram Tragedy Hustle

- An Instagram Post Promising To Give Food To Sudanese Children Got Over A Million Likes But It's Fake

- Does This Grandma Want You to Share Her Photo to Mark Her 100th Birthday?

- Fighting Engagement Bait on Facebook

- Facebook’s crackdown on “engagement bait” is long overdue